This is the second part in a series of essays about the history of films surrounding Godzilla. The first part, primarily concerned with the 1954 original, can be found here.

Godzilla was never created by radiation; it was reawakened. Lying dormant under the sea, the nuclear tests on Bikini Atoll brought it to the surface, empowered and angered by the nuclear bombings it and the Japanese citizens had fallen victim too. While Godzilla is ‘killed’ in the original 1954 film its an even more common occurrence for Godzilla to simply return to its home and await the next time its needed to defend Japan or destroy it (depending on its mood). This pretty much goes for the franchise as well. The Godzilla series has ‘ended’ four times and each set of filmmakers, be they Japanese or America, who have been tasked with bringing the beast back from its sleep has had to redefine the monster for whatever era they are working in. All this to say that rebooting Godzilla isn’t an event at this point, it’s more of a tradition.

However to understand the significance of these projects it’s important to understand the nature of the series, which is structured very differently to a standard American franchise. The Toho series don’t really have sequels, each Godzilla film usually ignores any established continuity except for the original 1954 film and even then, sticking to the origin established by Honda’s first entry is optional. Thus the only requirement for a Godzilla movie is that the big G pops up, villain or hero, and fights another monster or destroys some buildings (preferably both). Therefore you can have a serious Hiroshima metaphor in one film and invaders from the Moon in the next one. However the Toho films are divided into three series, and have loose common threads that could be construed as three separate continuities if you squint. The first one is called the Showa era (corresponding to the reign of Emperor Hirohito) and begins with the original dark masterpiece I discussed last week before spiraling into an increasingly silly kid-friendly camp-fest series before ending in 1975 to poor reviews and diminishing returns at the box office.

Which brings us to the first of many revivals of the franchise, 1984’s Godzilla (or Godzilla Returns in some markets), an attempt to return to the series to its darker political roots. From a production standpoint the 1984 film is interesting because it was one of the first examples of a back to basics gritty reboot before this became standard Hollywood practice in the 2000s. This iteration of Godzilla also stands apart as being the only Japanese Godzilla film since 1954 to not feature another monster for Godzilla to fight. The film in many ways retells the original storyline, although sort of hints that it could also be a sequel, but aptly updates the political anxieties to the tail end of the Cold War. Japan is no longer reeling from Hiroshima but is instead caught in a brutal tug of war between the USSR and Japan as to how to dispose of Godzilla. The superpowers (who are almost provoked into nuclear war in the ensuing confusion of Godzilla’s first attack) want to hit Godzilla with an A-bomb. The logic is familiar; thousand of Japanese citizens will die but it will save millions of lives everywhere, a rationale that could come directly from Truman himself. The alternative proposed by the Japanese government is beautifully symbolic; lure Godzilla to a volcano and destroy it there. It’s a race between man-made destruction and a natural order. As rich as the political overtones are, the film never approaches the glory of Honda’s original for the simple reason that it is never as visually virtuosic. Where audiences of the ’54 film viscerally experienced the bombing callbacks in the scenes of destruction and their aftermath, most of the meaty stuff here is reserved for the exposition between action scenes. The most striking moments of the film involve seeing Godzilla return to a new Tokyo, the Tokyo of an economic superpower. If Godzilla’s first attack was something of a takedown at Japan’s rapid capitalist expansion, then seeing it tearing down the neon skyscrapers that had grown higher in its absence is incredible. 1984’s Godzilla may not have delivered a masterpiece but its certainly a convincing argument for why modern Japan still needed a nationalist symbol that operated by brilliantly reminding its audience of their vulnerability as a nation.

After a seven film run over eleven years, Toho once again sent Godzilla back to the ocean to sleep, this time on its own terms rather than the box-office downturn of the original series. While the Heisei Series (as it came to be known) was enjoying a relatively profitable run, including some successful dubbing releases in the US, Hollywood was attempting to get its own version of one of the few non-US movie icons off the ground. By the time the project got off the ground Toho had finished making Godzilla films and the master of American destruction Roland Emmerich had been hired to bring the monster across the Pacific on the condition he could do the film the way he wanted; which amounted to basically ignoring everything except for the basic premise that a big lizard destroys things. It’s extremely important to understand precisely why Emmerich’s film is so reviled by fans of the franchise. It’s not just because the film is bad; the poor performances, overreaching CGI, inconsistent sizing and weak script still eclipse many of the weaker Toho films. What makes Emmerich’s Godzilla so offensive is that his creature is effectively not Godzilla. In fact by shrinking the monster and ultimately bringing it down by conventional military weapons, America tamed an untamable force of nature. 1998’s Godzilla wasn’t just a bad movie; it was a pretty offensive piece of cultural imperialism. Hollywood took the God out of Godzilla and thus Toho disowned the creature’s lineage, buying back its rights and renaming it Zilla.

What’s frequently forgotten about this Godzilla film is that, as reviled by critics and fans as it was, it still made a killing at the box office, coming in 3rd overall at the international box office that year. No matter how much flack Zilla took it had still made more money than any of its Japanese counterparts and thus many would remember it as the Godzilla. This prompted Toho to reclaim its most beloved property and go back to producing Godzilla films only four years after they had retired the monster. Godzilla 2000 (confusingly produced in 1999), returned Godzilla to its original design and country of origin. However this was not a somber, back to basics affair. Emmerich may have disempowered his monster but in (sort of) introducing Godzilla to Americans he labored the strangeness of a giant iguana stomping New York (even if it was suspiciously similar to the T-Rex’s rampage in The Lost World a few years earlier). With over 20 films depicting Godzilla’s fury, Toho couldn’t simply bring Godzilla back and remind audiences of its unmatched enormity. So instead they went in the complete opposite direction and created a film where Godzilla was a fact of life. Instead of fighting against the ubiquity of kaiju running around Tokyo, Toho embraced it and turned Godzilla into a symbol of resistance. If Americans could tremble at a smaller and easier-to-kill incarnation of Godzilla then the Japanese could brush off its more fearsome, radioactive counterpart as a fact of life. This Godzilla was louder and sillier than what was happening in Hollywood but it reclaimed the true Godzilla and spawned a successful third series of films; the Millenium Series (coincidentally the first series not to be named after an Emperor’s reign) which continued with varying degrees of seriousness and over the top silliness. It went out in a spectacularly camp fashion with 2005’s Godzilla: Final Wars, which saw Godzilla fight pretty much every monster in the series’ history including a trifling Zilla. The outcome? Godzilla thrashes its meek imitator almost as an afterthought.

Which brings us up to Gareth Edwards’ most recent addition to the franchise that never dies, only sleeps. It’s the first time Godzilla has come to screens in nine years, and sixteen since Hollywood tried their hand. Dominic Ellis’ review has already gone into the film’s strengths and weaknesses as a film but that doesn’t quite get into how it does preserving the monster’s momentous legacy. Edwards’ fatal flaw is trying to merge the series’ dark political side with its schlockier monster-on-monster action as well as awkwardly making Godzilla both terrifying and heroic at the same time.

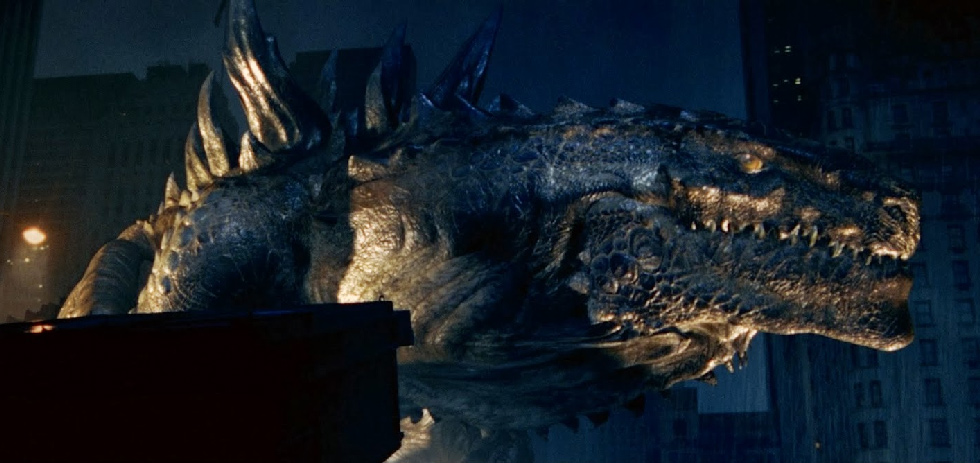

However for all its flaws, 2014’s Godzilla will never have the God ripped out of its name by a vengeful Toho because it has never been so unequivocally a force of nature. Edwards’ choice to ration the monster to the audience through overwhelming POV shots and frightening wide angles that contain a city but barely contain the titular character reinforce that Godzilla is so much more than a monster, let alone a character. While the man-in-the-suit techniques of Toho were actually rather brilliant effects for their budget, CGI has given Edwards the gift of completely removing Godzilla from any prosaic sense of character. Godzilla can never occupy a frame in a way that suggests we are its equal; we can only gaze up in awe or look on from a safe distance. Which is why, for all its faults, Edwards’ films captures a raw vulnerability barely ever seen in blockbusters. The Avengers, Batman, the Ghostbusters and the pilots who knocked King Kong off the Empire State Building have all saved the day but only Godzilla can decide when its done destroying everything you’ve built. Godzilla first emerged amongst the radiated bays of post-war Japan and he now returns to the sea amongst firefighters rescuing citizens from the dust clouds of fallen cityscapes. Just as Godzilla survived an atomic blast, it will survive the increasing lack of anxiety surrounding nuclear threats as terrorism, global warming and god-knows what else takes its place.

Godzilla is the slave at a Roman triumph, whispering in Caesar’s ear that no matter how powerful a man may become he is still mortal.

All the Toho Godzilla films are available through Madman Entertainment in a series of quite affordable DVD box sets. The 1998 American version is available independently on both DVD and Blu-Ray. Gareth Edwards’ most recent film is currently in theatres.