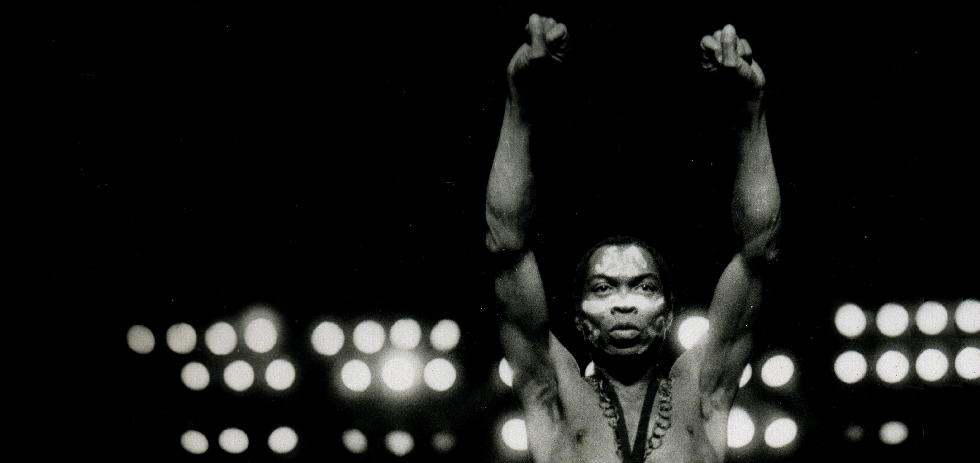

Alex Gibney has tackled the problem of power in many of his meditative documentaries, including the Academy award winning Taxi to the Dark Side. His film, Finding Fela, brings the fight to sub-Saharan Africa, and explores the interplay of politics and music in postcolonial Africa. We spoke to him after its debut at the Sydney Film Festival.

What was it that initially drew you to Fela as a subject matter? Was it his music or the politics?

I suppose it was both, really. I was drawn to the music and and the man himself. I got approached by Steve Hendel, who produced the Broadway show and when he approached me, I got back in. It was the combination of music and politics that attracted me.

It’s interesting that you bring up the Broadway show, because I noticed in the film a tension between the production of a Broadway show and the grassroots energy of someone like Fela Kuti. How does that reconcile in your mind?

It started out, honestly, the film was intended to be much simpler. Which was to say, you know, follow the Broadway cast back to Nigeria and watch them as they put on the show back there. But when I got there I started to become fascinated with the man himself. And when we got the footage, and started putting it all together, it wasn’t so interesting, it wasn’t so great. That’s when it got broader, and I started looking at Fela himself, the man himself.

I noticed the film’s epilogue was set in Nigeria – was that the locus of the old project?

Well, actually, the whole thing was set in Nigera – all those stage shots you saw were set onstage in Nigeria itself. I angled toward that. It all became part of finding out who Fela was, and what made this guy tick. That’s ultimately what the play is about, in the end, and the film was following [producer] Bill T. Jones and all his peeps trying to figure out how to make the play – that also is part of it. It’s like, he is a crazy character who made this incredible music, and how did that come about? It’s reckoning with that, and reckoning with who is this guy, and why did he have so much passion not only for his music, but for representing his past and ultimately being able to take all the bricks the Nigerian government threw at him? To endure this much pain.

On that subject, I noticed there’s a running theme in your films – The Smartest Guys in the Room, We Sell Secrets, Mea Maxima Culpa – which have, I suppose you could say, an anti-authoritarian or ‘challenge to authority’ bent to them. Do you think documentaries have an obligation to that purpose?

I don’t think there’s any obligation for any documentarian to do anything in particular except to showcase some aspect of life that people find interesting. But I personally am drawn to, you know, stories of power and abuse of power. And in this case, I guess, over time I’m becoming more and more interested in people who take on the powerful. The Smartest Guys in the Room is a heist film, in some way, and its mostly about, y’know, how these people pulled this heist. Of course, they ultimately come undone because of countervailing forces. Taxi to the Dark Side looks at how people abuse their power. This is a case of somebody – Fela Kuti – fighting back. That being said, I think the interesting thing about Fela Kuti is that he’s a guy who also became, I think, enchanted or intoxicated by his own power as a rockstar, and that took him to some places that we probably wouldn’t want to go. There are certain contradictions here. I’m more and more interested in the grey. You know, one of the most interesting pieces of music that Fela Kuti made, which is amply showcased in the film – not so much in the Broadway show, but in the film – is Beasts of No Nation, and that’s a very powerful piece of political agitprop, but at the same time the music is very meditative and spiritual. It’s not what you think of when you think about, you know, barricades music. That aspect of Fela Kuti’s art interested me a great deal.

Talking about political music, I found myself comparing it to last years Academy Award winner Searching for Sugar Man, in that they both talk about populist uprisings in Africa which have been charged by music. Do you think music is a compelling narrative for the very challenging sociopolitical issues and history of the continent?

Well I think it can be. Fela Kuti has that great phrase “music is the weapon”, and I think that phrase means more than “music is the drumbeat for some sort of protest action”; music is a powerful weapon because it unlocks the key to the human heart and that’s the thing the powerful can never overcome. And so there’s something indescribable about music that makes it powerful as art, which is ultimately what undermines the rigid, schematic and two-dimensional aspects of political oppression. There’s both a sense of fighting back in both a very direct, political way and fighting back in a deeper way, which is to emphasise the power of art. So that – music is the weapon – turns out to be a kind of double-edged sword.

You’ve mentioned, in some sense, the act of balancing one one hand the biography of a man compared with a broader picture of social movements in Nigeria. Towards the end of the film, you addressed the more contentious parts of Kuti’s personality, especially compared to 21st century attitudes to certain things: his cavalier attitude towards safe sex, his attitudes toward women, things like that. When we’re talking about a biography with such broad political scope, where do these challenging personal aspects fit in?

I think that people have to reckon with the full man. He’s not a saint. There’s a lot about Fela Kuti which was delusional. I think in some ways he was also going mad. But, y’know, it also came out of that sixties ethic of sexuality, where – for men in particular – sexual freedom was great, but there was a kind of oppressiveness about it. When AIDS started coming in, he refused to recognise that there might be something going on here, even though his brothers were at the forefront of understanding it.1 I think there was something very reckless and careless about that. He was into this kind of spiritualism that was seeing sex as something precious and self-centred – very destructive. But then, he was seeing it in a larger context, and there’s an aspect of it too which you have to see as, you know, let’s fuck, it’s good! He failed to see he was putting the lives of these women in danger, and you just have to reckon with that. He wasn’t neat and tidy that way. I think that’s one of the important things to reconcile within the film. But you need to see the other side too. Bill T. Jones said it: “Do I need to boil my art down to the fact I have AIDS?” There’s elements of the personal that aren’t properly attenuated in a larger social context, and then there’s the work of an artist, who’s doing something that is going to last for a very long time. I think it’s fair to reckon with both at the same time, but I think it’s unfair to say he put a lot of women in danger, so his art is no longer valuable. That I think is just wrong.

Staying with the political, you’ve made this film and Taxi to the Dark Side, which you mentioned before – I get a sense that you’re tackling a kind of colonialist or imperialist sentiment in foreign policy and history. There’s a lot of films at the Sydney Film Festival which run along those lines. What do you think Western filmmakers bring to the table in interrogating those problems?

It’s hard to reckon with that. What is a Western filmmaker? I’m not a person who is an expert in Africa, I’ve been there very little. I think as a documentarian, I think I’ve reckoned with the idea I can confront a subject and bring a sense of curiosity and wonder to it that is ultimately valuable. I don’t see myself as a poster child for Western documentaries. I see myself as an individual trying to understand what happens, to listen, to film and to reckon in a way that I haven’t done before – rather than coming in as an expert, I come in fresh to it all. To me, there’s nothing more valuable than a sense of curiosity and wonder. We all bring preconceived political paradigms to our efforts, but I think more important in a way is the sense of curiosity about the world which allow us to embrace the contradictions of everyday life.

Finding Fela screens as part of Sydney Film Festival’s “Sounds on Screen” program – it screens once more on Sunday 8 June. You can read our review of the film here.