It’s cold in London, worries Nikos’ mother; is he going to be affected by the snow approaching Scotland? Back home in Greece, it’s still warm – why doesn’t he come and visit? Her friend’s daughter is beautiful, and foreign women don’t know how to cook anyway. Nikos Gounaras (newcomer Theo Albanis), a dandyish but insecure ‘writer’ (the air quotes are vital) hounded out of credit-crunch Britain by an increasing pile of debts and bills, finds his everyday problems dwarfed, however, by the dark allure of his late father’s crumbling rural Greek villa in FX-wiz-turned-director Konstantinos Koutsoliotas’ debut feature The Winter. While at times the film’s ironic depiction of Nikos, self-absorbed, deluded, and hopeless, threatens to undercut its main themes, its impressive visual composition overpowers these issues. Steeped in an atmosphere of mysticism that largely succeeds in complementing rather than derailing its narrative, and bolstered by stellar, imaginative fantasy elements, The Winter stands out as a literate reworking of the Greek Weird Wave cycle.

The visual motifs established in the film’s opening act implied to me at first a film that would deal, however metaphorically, with the Eurozone crisis.1 Its opening credit sequence, panning across a sea of unopened bank bills, and the serio-comic scenes of Nikos scavenging around for a bed at mates’ places, suggest an effort to explore the experiences of the Eastern European underclass emerging in Britain. Some of the scenes here – the bizarrely-designed Kafkaesque office from which Nikos is soon fired by a boss who speaks in vague business buzzwords, the startling contrast between Nikos’ eccentric figure and his drab street – begin to showcase the odd, rigid composition favoured by recent celebrated Greek films such as Yorgos Lanthimos’ 2012 SFF winner Alps. The Winter, though, uses the formality of some of its cinematography to enhance the effect of its more fantastic elements. As a result, though, it’s these early scenes that are the film’s weakest – without the juxtaposition of its tight framing against the magical stylisation which comes later, The Winter’s early scenes often appear posturing. Nikos’ penchant for Russel Brand waistcoats, trendy haircuts and – I’m not kidding – stovepipe hats plays into his depiction as a wannabe intellectual to an uncomfortable degree, and makes him a wildly unlikable character for longer than the film intends him to be. As an aside, it’s also jarring to see the international filmmakers’ borderline dystopian vision of modern Britain and its inhabitants; between plummy professionals, the priggish call centre employees who hound Nikos over his debts, and the obligatory foulmouthed chav, I finally understand how Australians feel watching Crocodile Dundee.

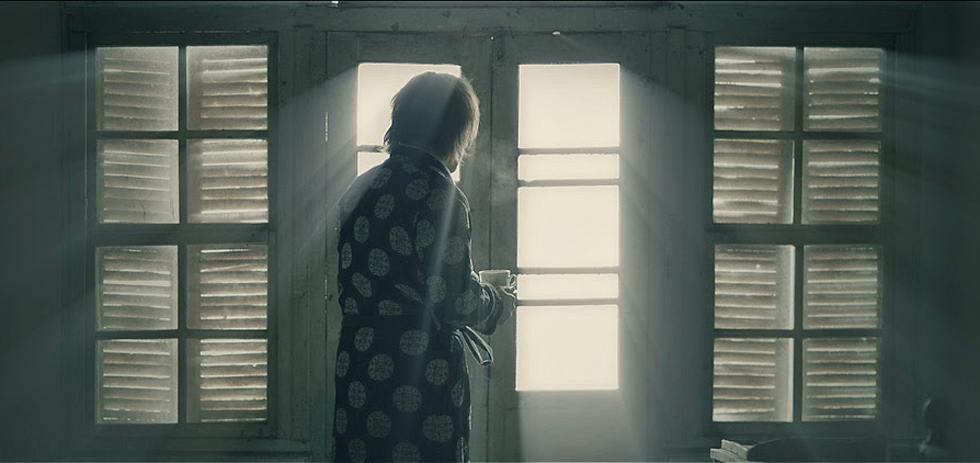

These quibbles soon evaporate, though, when the film relocates to the ramshackle Gounaras family home in dusty northern Greece. Nikos ostensibly retreats there to write his novel, but it soon becomes obvious that he is seeking more than creative inspiration – his father Dimitri (Vangelis Mourikis), divorced from his mother (Petroula Christou, as a voice over the phone only), also holed up there for years before his rarely-discussed premature death. The strength of The Winter, which really becomes clear here, is in its uncanny ability to use the developments Nikos undergoes in the mundane parochial town of Siatista as an effective narrative anchor, giving the film’s wilder moments of pure fantasy a more compelling human edge. His interactions with the batty old lady living nearby who reads tea leaves with little accuracy, the town’s authoritarian Orthodox priest, and Eri (Vasiliki Panali), on whom he develops a schoolboy-like crush, draw a portrait of a community where tradition, myth and modernity fuse into a serene but somehow threatening whole. When this more straightforward narrative is disrupted as Nikos begins to experience visions formed of distorted memories and elements of his family’s folk tales, Koutsoliotas and Elizabeth Schuch’s script never deviates from a basic integrity. It doesn’t hurt that the special effects, when employed, are fantastic in both senses of the word – Koutsoliotas’ film industry chops were earned in Hollywood as a digital compositor on this year’s Guardians of the Galaxy and the 300 sequel. It’s to the film’s credit, too, that the possibility of an explanation for Nikos’ dreamlike visions is left often to a variety of interpretations – to say more would spoil too much, but I favour the idea that he is beginning to suffer mental illness in the vein of his father.

By the conclusion of The Winter, it becomes clear that the film is really about stories: those we tell each other to bring comfort, like the extended animated fable which a young Nikos hears from Dimitri in a flashback at the film’s midpoint; those we tell through what we create, like his doomed novel; and those we tell to ourselves, like the ruse of Nikos’ successful London life or what he wants to believe about his lovable, rambunctious father. All of these tales are given the lie by the film’s final shots; when Nikos burns his dead-end book manuscript outside the house, the surprisingly dry, bright weather of the rest of the film – it takes place in December – appears to transform. The ashes of the pages look like snow against the sky, and finally it’s really the winter.