These Heathen Dreams is a rare documentary in the same way that Christopher Barnett is an incredibly rare individual. In her film, Anne Tsoulis doesn’t put forth an argument that frames him as an under-appreciated artist, nor does she paint him as a tortured genius, or, really, any other artist-documentary cliche. Instead, these traits emerge in different, more nuanced forms, due to to Tsoulis’ decision to create a more honest documentary; one that doesn’t bypass the current existence of the film’s subject, but instead chooses to relish in it. Anne Tsoulis’ These Heathen Dreams is framed by scenes of Christopher Barnett in the present day. Living in Nantes for the last two decades, Barnett is portrayed as a pariah who has renounced the country that renounced him, with little intention of going back (in a scene that drives this point home, Barnett is shown giving his Melbourne ‘book reading’ via Skype).

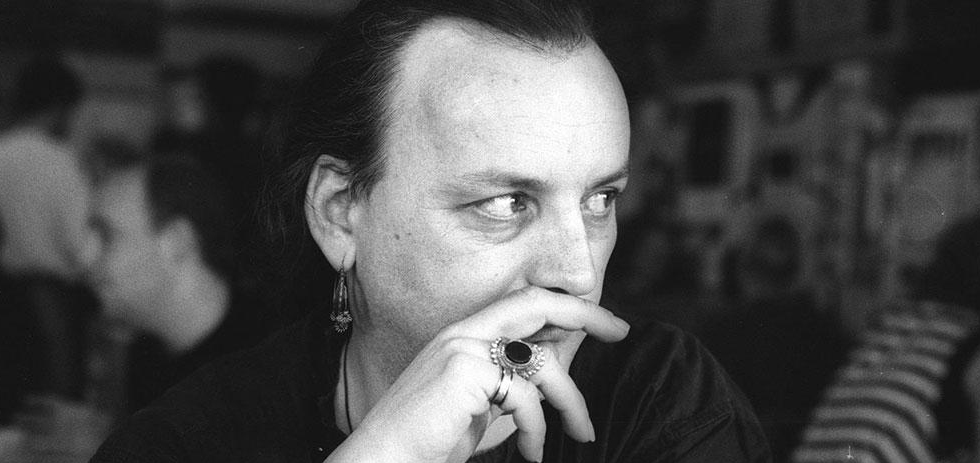

Barnett is old in the film, however, despite his physical changes, Barnett’s enigmatic anger, intimidating intellect and his constant overpowering presence remain the same. His present day life in Nantes is interwoven with archival footage of Barnett giving poetry readings, lighting cigarettes in alcohol and drug-fuelled dazes and other figures lauding his relatively unacknowledged contribution to the Australian art sphere. Most notably is Paul Kelly, who associated with Barnett from his teenage years. In one of the most telling scenes with Kelly, he compares himself to Kerouac and Barnett to Neal Cassidy, arguing that while Kelly become revered by a broader section of society, the people who Barnett connected with saw a human reaching for something more primordial, abstract and, at times, terrifying.

Throughout the film, Tsoulis takes a microscope to the idea of sickness, a loss of ability,and the constant interplay between the physical and the mental. In a scene where Christopher Barnett visits Thomas Harlan in hospital – both discussing their respective sicknesses – the film takes shape with this certain sense of rare intimacy. Both figures are at their most vulnerable, yet they are presented with a certain delicacy that doesn’t present them as fragile, but as something rather complex, passionate and incredibly human.

At times, Tsoulis’ film is as much about Christopher Barnett as it is about Thomas Harlan. Their endless history and the theatre of their current existence is responsible for much of the interest developed throughout. In one of the film’s more memorable lines, Harlan – on his back, connected to a series of wires and tubes for his sickness – looks at Barnett and tells him that his “relationship to the present is very weak.” This temporality, disconnection from the present and malleability of time permeates throughout much of the documentary. Barnett remembers his life through Harlan and in a state of isolated intimacy with him. They are alone, together, in the film. Harlan’s passing since filming adds another element to the documentary – the subtext that this rare intimacy is no longer exists, that Tsoulis has captured it on film, and that both figures have allowed their relationship to be recorded in such a way. Their conversations collapse the present, promulgate an intensely detailed and rich history and present the audience with a stunning close-up of a figure as complex as Christopher Barnett in the process.

There are endless documentaries that focus on great figures, well known to society, that have received an audience for their work in their time. When a documentary locates a figure that lacks this position, they are uncovering something far more scarce. Anne Tsoulis has located an incredible subject in Christopher Barnett, but at the same time, she has constructed her documentary around him in a way that doesn’t feel retrospective or historical; but instead a painstaking character study in the present. At times it feels like an interview, at times it feels like a portal into a lost time. Throughout all of this, however, Barnett is at the centre and is ‘documented’ in a way that is both fresh and markedly humanist in its study of him. Tsoulis has created something that revels in and goes beyond its traditional form, resulting in a fairly special, intimate and careful documentary.