You Have to See… is a weekly feature here at 4:3, where one staff writer picks a film they love and makes a group of other writers watch it for the first time. Once this group has seen the film, the suggestor writes a piece advocating the film and the others respond below. Whilst not explicitly spoiling the film, the article is detailed. We would recommend seeking out and watching the film each week, then joining in the debate in the comments section.

This week Jim Poe looks at the acclaimed Rolling Stones-centric documentary Gimme Shelter.

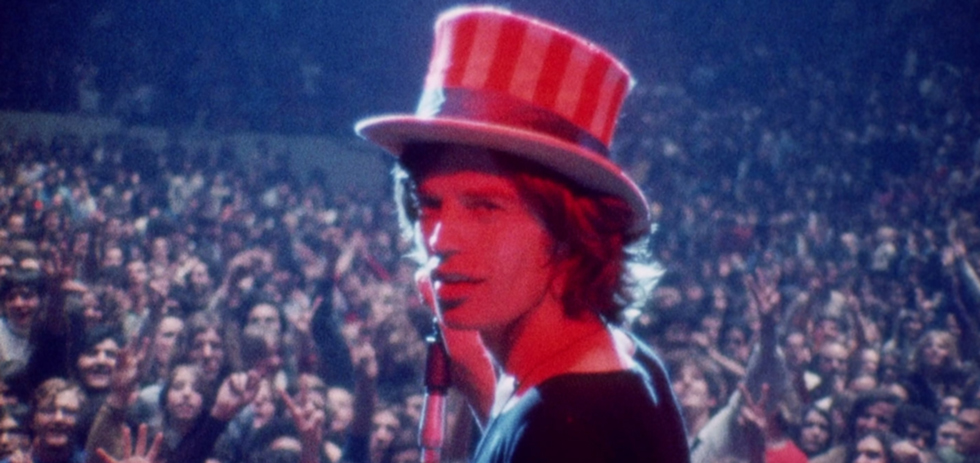

When you step back and look at it, there’s an appalling perfection to the whole scene. All the elements are in place. Here we are at the very end of the 1960s, in the countryside outside of San Francisco. It’s cold: it’s late autumn, and night has fallen. The Rolling Stones, at the height of their powers, the self-styled greatest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world, are playing a free concert for 300,000 freaked-out hippie kids. Mick Jagger stands onstage, dressed in a red-and-black harlequin’s costume, and sings from the perspective of Satan. He’s surrounded by Hells Angels and bad vibes while the seething crowd presses in. Then one of the gang members stabs and kills a young black man, Meredith Hunter, right in front of the stage. But amidst the mayhem, the band don’t see it happening, and they continue the show. The plain facts are so loaded with symbolism and saturated with drama they’re over the top, as if the whole thing was written by Oliver Stone. It’s one of those moments in history that seems less real the more you ponder it.

Gimme Shelter was released in 1970, the year I was born, but somehow I made it into my forties without having seen it. I finally experienced it this month, when its restored version screened at Sydney’s Antenna Documentary Film Festival. I’ve always been aware of the implications of the word “Altamont,” without having actually seen any of the footage. Like “Watergate,” the name of that place in Alameda County resonates far beyond the event itself. “Altamont” means the Waterloo of the ’60s, the last stand, the anti-Woodstock, the place where the dream was killed like a sacrificial lamb. It’s taken on the proportions of myth. It’s all oversimplified, of course, originating from sensationalist media coverage and a generation’s search for meaning. Still it’s hard to avoid attaching significance to what happened there on December 6, 1969. Four months after Woodstock, a free counterculture festival with nationwide publicity went badly wrong, something like anarchy ensued, a young man was killed by bikies. And Albert and David Maysles were there with a big camera crew to capture it all in detail. Trading in that mythmaking while slyly analysing it, Gimme Shelter is considered one of the greatest documentaries ever – and I think many would argue one of the greatest films ever.

Not without controversy. The Maysles have often been criticised for making themselves part of their stories, clouding their claims to Direct Cinema, and so it is with Gimme Shelter. Even before the film was released, critics questioned the Maysles’ involvement in the tour and the planning of the show.1 They were even accused, in Rolling Stone’s seminal report and later by Pauline Kael and others, of masterminding the entire thing – all of it, the location, the staging and lighting – so they could shape the perfect rock ’n’ roll documentary, with tragedy the result of their grandiose zeal.2

This harsh and somewhat silly judgment has been firmly denied by the Maysles and debunked by other eyewitnesses. In any case, when you’re actually watching the film, the idea that anything that happened at Altamont was planned by anyone goes right out the window. So does the thought that this is a “rock ’n’ roll film.” It’s more like a study in elemental chaos. After a point it doesn’t even feel like a documentary. There’s a dreamlike quality that makes it seem, true to theme, like a bad trip. Plenty of documentaries show us terrible things that really happened, but Gimme Shelter is unique in how completely and viscerally it places the viewer in the midst of a deteriorating situation, to helplessly witness a nightmare as it unfolds. It almost functions as a horror film.

True, there are somewhat more conventional music-doco elements in the first half of the film, covering the Stones’ 1969 tour of the States. We see some of the iconic show at Madison Square Garden, the sessions at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama that resulted in “Wild Horses” and “Brown Sugar,” snarky press conferences, backstage antics. The Maysles were masters at that crucial documentarian’s skill, ingratiating themselves to their subjects, and both the live-in-concert footage and the candid stuff is fascinating in its eye for detail and its patience. In front of the Maysles’ probing cameras the Stones do some clowning, get drunk a bit, look tired a lot, and carry themselves with an easy swagger. It’s never mentioned in the film but they’ve just been through tragedy: their founder, the troubled Brian Jones, drowned that summer.

Even before we get to Altamont, the film’s editing exhilarates; editor Charlotte Zwerin earned a co-director credit for fine work. On one occasion, we watch the band listen to a playback of “Wild Horses” just after recording it; the song plays in its entirety, with the camera lingering on each band member as they concentrate on the recording – Jagger, bottle of whiskey in hand, trying to supress a triumphant smile, Keith Richards leaning back, tapping his snakeskin boots. The quiet intimacy and the song’s slow-burn crescendo are an emotional touchstone forming an important contrast with the catastrophe to come.

Even if you know nothing about Altamont, the film’s structure creates a sense of doom, the dissolute glamour of the tour funneling towards disaster. In an early scene, Jagger and drummer Charlie Watts sit in a studio with the Maysles and Zwerin and listen to recorded radio coverage of Hunter’s death weeks after it happened. Their conversation, trying to unravel the debacle, is appalled but guarded. Is the blithe, cocky Jagger capable of expressing real remorse? The film asks the question but doesn’t try too hard to answer it. Throughout, footage of the tour and Altamont is intercut with shots of the band watching the same footage in Zwerin’s editing bay. The intricately layered film within a film, the running juxtaposition of the spectacle of the tour against the shocked, weary aftermath, create a detachment that makes the film much more than a straight doco. The making of the film is implicitly part of the story. Whether this represents an attempt on the part of the Maysles to address the critics or a kind of cinematic bravado has been the subject of debate. Godfrey Cheshire, in his great essay for the Criterion edition, compares Gimme Shelter to Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up in its “strange fascinations and self-enclosing revelations.”

Between shows and recording sessions on the East Coast, the Stones and their people hurry to arrange the free gig in California at the end of the tour. This was done partially in response to allegations of un-hippie-ishly extravagent ticket prices, and partially out of a competitive effort to up the countercultural ante and create a “Woodstock West.” But there are many planning problems: various local authorities are determined to prevent such a huge gathering of hippies, the venue is shifted three times, and the owner of the eventual location, the Altamont Raceway, tries to play hardball in sealing the deal. Famed attorney Marvin Belli, who defended Jack Ruby in his trial for murdering Lee Harvey Oswald, negotiates all this in a loud, cartoonishly self-assured manner over several conference calls.3 It’s a droll reminder that some of the movers and shakers of the ’60s, or what we think of as “the ’60s,” were hard-nosed establishment types. But days before the gig it’s clear nothing is actually in place, while thousands of revelers are already on their way to the scene, many from out of state.

If you know anything about event production, if you’ve ever been a musician or performer, or even if you’ve simply been to a lot of gigs, watching the film you’ll see all the ways the organisers got everything as wrong as possible at Altamont. They really did think they could just slap a day festival together and the goodwill of the counterculture would carry it through, as it did at Woodstock.4 It’s a wonder more people weren’t hurt or killed.5 There was no plan for parking – one crewmember comically tells another they’ll just stop worrying about the parking and let it become an experiment. The stage was a shoddy construction, built way too low – barely a metre high, more suitable for community theatre or a high-school musical than a massive festival. It was situated at the bottom of a dell, with no barriers to block it off. By the laws of crowd dynamics, it was inevitable that thousands of people would continually pour downhill and right against it like a human avalanche. The backstage area was made up of a few trailers and vans right next to the stage, and was frequently invaded by punters, as was the stage and the rigging. At one point you see a lighting rig sagging dangerously under the weight of the mischievous kids who’ve climbed onto it; a frustrated promoter urges them to climb down, to little avail. There was not much security to speak of. The arrangement for the Hells Angels to stand in front of the stage and try to enforce some order was an impromptu one made on the day, and may have been done simply to placate them. The Angels had a way of rocking up to gigs and getting whatever they demanded.

The Stones disappear as subjects for a long stretch as the free concert takes shape, and Gimme Shelter becomes another film entirely. The hasty site construction, the swelling crowd, the hopeful energy, the ominous signs of negligence and the intimidating arrival of the Angels are established brilliantly by the filmmakers. It’s really something that such an epochal event was filmed so thoroughly – the Maysles were probably the only ones at Altamont who knew what they were doing. They had at least 20 cameramen at work on the day, and their coverage is amazing, ranging from the top of the hillside looking down on 300,000 people, to right onstage, so close to the performers you can palpably feel their nerves. The 45-minute sequence that Zwerin sculpts out of what must have been hundreds of hours of footage is scintillating, a cinematic wonder.6 Time and again we cut away from the stage to shots of individuals in the crowd up on the hill, each snapshot so full of colour and creativity and life – costumes, balloons, dancing, lovemaking, many of them young people of colour in an age when different races didn’t mingle as much. It’s as though we get to know all of them. Yet each shot adds to the mounting tension as dusk falls, as many of them come to realise this is a bad scene, and a few react to what must have been some really dodgy acid going around. The astonishing overhead shots show just how dangerously crowded and unruly it all was – at one point you see a guy tripping his balls off, crowdsurfing on top of people who are sitting on the ground and hemmed in shoulder to shoulder all the way to the horizon. Among these fearful flower children the Hells Angels are drunken wolves loose in a sheepfold.

The grainy footage of this tumult, illuminated first by a bright, angled December sun, then by the blue-grey gloaming, then by harsh stage lights, is hypnotic. Cheshire’s take in his Criterion essay is spot on:

The climactic scenes at Altamont have a beauty that’s all the more alluring for being so damned and damning. The scene, lit by fires and hazy with smoke, looks like some medieval village of the godforsaken, yet the 16mm images – much of the camerawork is extraordinary – also make it appear as heroic and ruggedly elegant as a disaster painting by Delacroix.

There’s such a 360-degree quality to it all, the way it depicts the pressure of the crowd on every side, breaking against the brutality of the Angels, sometimes washing up onto the stage. There are so many astonishing shots with Jagger trying to sing or Richards trying to play and you can’t work out where the stage ends and the crowd begins; or one of the band in the foreground while we study the face of a punter in the background; or weird, Lynchian details, like the German shepherd that appears onstage out of nowhere. As one melee after another breaks out, with full-blown panic swirling the crowd like rip currents, it’s clear there’s no more control. The imagined weight of all those people and all that anxiety is suffocating. As much as I love a good gig, I’m a bit claustrophobic in very large crowds; during the screening I actually got out of my seat in the front row and went to stand at the back. I think I just wanted to be a little further away. Being there must have been overwhelming.

It shows on the faces of the band – the Maysles’ intimate camerawork again shines here. “Oh babies. There’s sooo many of you,” Jagger looks out and tells the gathering when he arrives onstage, and you can tell he’s spooked. Later, after pleading again with the crowd in front to calm down, he turns to Richards and says, “I don’t know what the fuck we’re doing.” It seems he’s overmatched by this situation – the arrogant, wealthy, dandy Londonder on his first US tour in years, confronted by thousands of scruffy California freaks, many of them homeless, some desperate enough to resort to violence. He’s lost in the wild west.7 It’s like the sign of the counterculture meeting the signified. His preening and chicken dances seem so childish and hopeless. Yet there’s also something admirable about the way he and the band react; the shaky, clenched version of “Under My Thumb” is extraordinary. Near the end, the cocksure “It’s all right!” becomes an urgent, keening, “I pray that it’s all right.” It wasn’t, because Hunter was killed moments later. But you do wonder how much worse things might have gotten if they’d stopped playing. It would be a slippery slope, or just a dumbass rawk cliché, to say they rose to the occasion – someone died after all. It’s more that the film makes it apparent that they were just five people in that crowd. Everyone was doing their own thing to deal with it; they happened to have instruments in their hands.

Hunter’s death, the focal point of the film and the legend of Altamont, is at first somewhat anticlimactic when it comes. Blink and you’ll miss it, though it’s obsessively rewound and frozen at the conclusion. Even then it’s not completely clear what’s happening, and, as real-life death so often is on film, it’s pathetically awkward and clumsy, as Hunter in his lime-green leisure suit is jostled around by his killer like they’re slamdancing. But days after you see the film, the blurry shot of the flashing knife, Hunter’s brandished pistol and the doomed kid exiting the frame with vicious force will haunt your memories, the lime-green suit surrounded by indistinct shadows then gone in the darkness, the strange fruit of that thorny tangle of discord and bad blood.

I had somehow forgotten that Hunter was black until I saw the film.8 It lends a whole other dimension to Altamont and to the film. Weeks later, his killer, Alan Passaro, was acquitted of murder on grounds of self-defense. Of course he was acquitted! Fair enough, Hunter was armed and high on meth, so to suggest that he was the Trayvon Martin of his day is probably off the mark. The fact remains that Hunter was stabbed in the back five times, and kicked and stomped on by Hells Angels after he fell. It would be hard to argue that race wasn’t a factor at all. The Angels are infamous for the persistent racism in their organisation. Anyway, we’ll never hear Hunter’s side of the story – he’s gone. There’s not much information about him available.9 He was an arts student at Berkeley, so he must have been very much part of the era, very much a part of his generation. He had a white girlfriend. his sister says he was a bright kid who would never have hurt anybody.10 His grave in East Vallejo, California was unmarked for decades, even as his death served as an overloaded symbol of the death of his generation’s innocence.

The Stones, none the wiser, kept playing after Hunter died. But the film ends there, as if the Maysles and Zwerin have nothing more to say, as if the awful gravity is too much for further commentary. The inscrutable look in Jagger’s eyes as he turns away from the Movieola is what we’re left with, along with the queasy impression that something so ugly and catastrophic became a great, generation-defining work of art because the Maysles were there at the right time and right place to capture it on film.

Responses

Felix Hubble: While I can’t say that I found the first half particularly noteworthy, the second half of this documentary was fascinating – especially as a big fan of the horror genre. When Gimme Shelter moved its focus away from the logistics of pulling off a huge, free concert and turned into a document capturing an evening of pure tension and unimaginable terror, the Maysles’ and Zwerin sunk their claws into me and never let go. I can’t recall ever seeing a documentary that has had me this on edge or stressed out before, that so actively captured the reality of an event of pure horror. It’s amazing ability to place you in the audience among the punters in the front row, as their moods begin to deteriorate and they become fearful of what is inevitably about to unfold is a triumph of documentary filmmaking and places this film firmly in the has-to-be-seen documentary canon, even with its more Stones-fan-centric first 40 or so minutes. There’s so much to be said about the film’s final moments, yet rather than overanalysing the situation the filmmakers leave nearly everything unsaid. While there’s some agenda here (as there is with every film) the Maysles are not here to shove it down their audiences throat and that, perhaps, is the film’s greatest asset.

Although I think a lot of the film is lost on me as I have never been that big of a Stones fan, I can fully comprehend Jim’s adoration of Gimme Shelter. I don’t have much to say about the film that Jim hasn’t already said in a far more elegant fashion than I could possibly achieve, although I will say that if you’re not the biggest Stones fan, but you do listen to a lot of music and have been to a lot of gigs, there’s a lot here for you. The sheer enormity of the event and complete shambolicness with which its been thrown together is fascinating and almost even admirable in its own punk-rock kind of way, and its a great shame, although probably inevitable, that the administration of the Altamont Free Concert had dire consequences. There are so many fascinating pure, human moments throughout the film. Of particular note is a shot in which a Hell’s Angels member whispers something in Mick Jagger’s ear, causing him to break from his stage persona for a moment and look out across the crowd at an ensuing brawl, before recommencing his chicken dance with a look of fear strewn across his face. The terror here is well and truly alive.

In lieu of extensive footage of Woodstock ’99, this is definitely the counter-film to Wadleigh’s 1970 documentary Woodstock and is a worthy watch for any fan of the documentary form or rock history in general.

Conor Bateman: I’m tempted to just write “ditto” because Felix seems to have captured most of the way I feel about Gimme Shelter. I think there’s an almost messy shift within the film from the more atypical rock documentary format of the first concert show we see and the horror and persistent tension of the Altamont section of the film. Whilst the Maysles and Zwerin introduce a very clever element in having the Stones watch back the footage, it doesn’t feel like this element is actually harnessed enough, the sudden freeze frame at the end on Jagger a clumsy pointed message of distance, contrasting their direct cinema style throughout. That said, the film remains quite a bold cultural artifact, and as soon as the film actually focuses on the Altamont free concert, even with the amusing legal wrangling over the telephone (Jim says Belli looks out of Mad Men, I’d lean towards Brian Cox in Zodiac), it becomes incredibly compelling.

As Jim writes, when the Stones disappear from the concert film for quite a length of time as the supporting acts (including Jefferson Airplane) deal with the increasingly chaotic crowd, the film becomes something else entirely. The uninterrupted music that punctuated the first half, scenes in which the Stones lie down and listen to their own tracks, isn’t even close to possible in this second half, guitar licks forced into repetition as crowdmembers jump the stage and the Hells Angels deliver beatdowns to all and sundry. That distance between the performer and the viewer is, in a sense, shattered, both physically and mentally, as we see Jefferson Airplane react to the bikers, one of their singers, Mike Balin, is beaten.11 The contrast between the two halves does become much sharper when the Stones themselves come onstage. They no longer have the safety and security they did in the first concert we see, where crowdmembers running onstage were quickly carried off by security. Here if someone causes trouble, they get a pool cue to the head.

Whilst the slow-mo repetition of the stabbing is searing (in fact perhaps the realtime speed, where you think you see something in the back of a shot is even more powerful), it’s not the moment that sums up the film. There’s a brilliant shot in which we see one of the Hells Angels lean into Jagger and whisper something in his ear, at which point Jagger, still dancing slightly, moves near the front of the stage, sees something, and suddenly comes to a standstill. He didn’t see Hunter’s death then but you get the sense he’s watching a fight from afar. There’s a pause, he doesn’t know how to react, then he snaps out of his trance and starts dancing again. That flash of surreal humanity is documentary gold and Gimme Shelter, whilst not always that brilliant throughout, is a mostly fascinating affair that leaves room to ruminate on fame, music and stardom.

Brad Mariano: I approached this film with the tiniest bit of apprehension, only because a similar Rolling Stones film – Jean-Luc Godard’s hybrid ‘documentary’ Sympathy for the Devil, released the year earlier – was so tiresome and excruciating, which feels like little more than a camera that forgot to stop rolling through the band’s least interesting rehearsal sessions. Gimme Shelter, however, even in its less engaging stretches (which I’ll agree with Felix is essentially the first half) is still of interest even to non-fans of the band, but the magic doesn’t happen until we arrive at Altamont. The first few scenes from a helicopter are staggering, following along miles of road with barren landscape on either side, and cars bumper to bumper parked alongside it. In a case of both life imitating art and an attempt of mine to shoehorn Godard twice into this piece, there’s a shocking sense of cinematic deja vu, recreating that famous car scene in Weekend (1967) – a connection that seems fitting, with Altamont’s scenes equally brimming with counter-cultural potency and alarmingly, only slightly less outright anarchy. But as Jim notes, it’s not all bad – there’s a real euphoric sense to the early scenes, of joy and vivacity even as we brace for the shit to hit the fan. And boy, does it ever. The film so clearly shows the tensions and problems of the festival and all its absurdities, and I too was going to mention the German shepherd, we have no idea who it belonged to or how it got on stage, but of course there’s a fucking dog on the stage. When you’ve seen bikies thrashing hippies with pool cues played out as the festival’s official law and order, all logic is thrown out the window and you kind of just accept this truly bizarre universe and the forces within. And there’s something chilling about those final scenes as this film becomes the musical Zapruder equivalent. With documentary filmmaking it’s often better to be lucky than good, and when the filmmakers are both as the Maysles brothers are here, you end up with an essential pop culture document. Did I love the film? Not overwhelmingly per se (the first half requires full on Stones fandom to really appreciate) and I can’t see myself revisiting often, but this film unquestionably satisfies this column criteria, being one that undoubtedly You Have To See.