Reading a review of Angelina Jolie’s soon-to-be-released second feature as director, Unbroken, carries with it a curious sense of déjà vu.1 The film’s plot is pretty familiar biographical stuff, for sure, dealing with the late Olympian and US war hero Louis Zamperini, whose survival of a series of incredible wartime traumas – a plane crash, weeks at sea in a life raft, brutal treatment by the Japanese – tells a palatable enough Yankee Doodle Dandy tale that it can hardly be said that Jolie’s decision to helm the film constitutes a great artistic risk. There’s something recognisable about reviewers’ criticisms of Unbroken, too: a three-star Guardian review is disappointed by Jolie’s “stolidly conventional approach to the material,” while another decidedly more caustic piece concludes that the film “gets us barely further than a poster,” lacking any of the incisiveness required to tell the more troubling aspects of Zamperini’s story. Is this not, in all honesty, the stock critical response to films made by major Hollywood actors? Paired with her debut, the similarly tepidly received Bosnian war romance In the Land of Blood and Honey, Jolie’s career as director is shaping up to function as an extension of her existing star persona – goodwill ambassador, earth mother, justice warrior. We can no doubt expect from her a few faux-gritty films shot in appallingly poor parts of the world, maybe a documentary about animal rights, and finally, to recoup their inevitable box-office losses, a slapstick comedy about slashing Jennifer Aniston’s tyres.

The list of actors-turned-director goes on and on in this vein. While The Passion and the Christ and Apocalypto both had their moments as pieces of primal high-concept cinema, it’s abundantly clear that Mel Gibson made them because he felt like seeing them; the gimmick of recording dialogue in dead languages paired with vaguely masturbatory violence may well echo Mr. Gibson’s famed ego. Kevin Spacey, less offensive but far more offensively dull, chose to make a biopic of the crooner Bobby Darin his first directorial project in 2004. Beyond the Sea, with Spacey also starring, co-writing and co-producing, did exactly as well at the box office as you would expect a biopic of everybody’s seventeenth favourite ’60s musician, Bobby Darin, to do. Even Denzel Washington has been in on the action, albeit with his trademark sobriety, having the decency to stick to what he knows with Antwone Fisher and The Great Debaters, solid if unspectacular films dealing with little-known chapters of African American history. Alternatively, “let’s go and see the new Sean Penn film,” said no one ever. Even the hugely popular Into the Wild follows the tested formula above, melding a real-life (uncontroversially male) character study with touches of the star-director’s own persona.

There are exceptions to the formula, of course. Clint Eastwood’s ’70s output as director was largely utilitarian, allowing him to perform his star image on his own terms at the height of his popularity in High Plains Drifter and The Outlaw Josey Wales. His more recent films, however, are becoming more interesting as Clint becomes more of a cantankerous crank, and as the gravity of his status as filmmaker begins to challenge his status as film star. Gran Torino functioned as a peculiarly entertaining piece of pure libertarian cinema in line with Eastwood’s own well-publicised politics; e.g., chubby Asian kids just need to walk onto construction sites and get jobs there, and they can thereby overcome the omnipresent spectre of gang violence and cultural disconnect. Even fewer actors can make good films themselves while maintaining an acting career in others’ movies – the endless critical dissection of last year’s Gone Girl had a fascinating subtext, as Ben Affleck’s then-recent emergence as a meaningful film director (The Town, Argo) complicated his acting performance in a major auteur’s work. Discussing David Fincher as an ‘adaptor’ of Gone Girl’s source novel was given a new layer when considering Affleck as a potential co-author of any film in which he now appears.

What is even rarer than a Hollywood A-Lister morphing into a mediocre director, and a thousand times less common than a superstar becoming a world-class one, is movement in the other direction. A thought exercise: see above, where I took a shot at a few actors who have made less than stellar films. Can you do the reverse with cinema’s great directors? Hitchcock, for example, as an actor? While his ego was undoubtedly massaged in other ways, most obviously the cameos in his own films that spawned a cottage industry of Hitch-spotters, he never made a genuine acting appearance. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick made a couple of token cameos in his own films but never got paid to say lines, hilarious though the image of him as Seth Rogen’s dad in a wry stoner comedy might be (that actual role, in Knocked Up, was, however, played by Harold Ramis, a director in his own right and a rare crossover success). While a list of non-acting directors could go on forever, it’s the exceptions that are interesting. For every dozen Ozus, Fellinis and Bergmans who stayed resolutely on one side of the camera, there’s a director who did make forays into acting. These instances range from relatively straightforward – Ramis, for example, as a National Lampoon writer and performer, has never possessed a huge enough star image to compromise his filmmaking, or vice versa – to, more frequently, intriguing and bizarre. The most unexpected and most rewarding on-screen appearances by renowned film directors can even prove revealing about their own films, the trajectories of their careers, and the status of genre, auteurism and introspection in mainstream cinema at a given place and time. I suggest four categories of acting appearance for renowned film directors, ranging from the parochial to the political, the preposterous to the perverted.

THE HOMAGE

Some of the earliest calculated director-casting, unsurprisingly, comes from Europe – the notion of a film director functioning as the fundamental author of a work, however much it would later be complicated in US film criticism, has its roots in the theatrical tradition of German and Scandinavian silent film, and was most significantly put forward by French critics in the ’50s. As such, the idea that casting could pay homage to a filmmaker’s work and/or image appears to have germinated in those areas. One of the most touching examples of a filmmaker appearing as a character in another’s work comes from this early period, when the legendary Swedish silent era figure Victor Sjöström acted, at age 78, in Ingmar Bergman’s 1958 film Wild Strawberries. Sjöström had in fact been a significant actor, mainly in his own films (Terje Vigen and the superlative The Phantom Carriage in particular), throughout the 1910s and ‘20s, but – aside from another less-feted Bergman role a few years previously – was unknown as a performer thirty years later. As a star, he cut a proletarian figure unfamiliar to us as a modern audience, his doughy physique and atrocious dad-moustache evoking the 1800s’ socially conscious Scandinavian theatre tradition and some kind of old-time Ron Swanson in equal measure. On the other hand, his performance in Wild Strawberries is a revelation: resonant many decades later as a moving portrayal of old age, Sjöström plays Isak Borg, an embittered university professor travelling across Sweden to accept an honorary degree with his son and daughter-in-law. The elegiac tone of the film, with Borg recalling the more sentimental moments of his life as it nears an end, is perfectly expressed by a lead performer who himself had seen a golden era come and go and now rested in the twilight of his life – indeed, Sjöström would pass away around a year after Wild Strawberries was made, leaving a domestically-respected but internationally-unknown body of silent film work in much the same way that Borg leaves his earthly accolades and professional prestige.

In the end, of course, it’s the people, places, and experiences we remember. An interview with Bergman for his 80th birthday coaxed out of the Swede the resentment he felt while the film was made, as he became aware that he was trading largely on his lead actor’s image – it was suddenly “Sjöström’s film, and [Bergman] felt he was losing control,” as Amir Cohen-Shalev writes. In truth, though, it was this prevalence of character over directorial voice that elevated Wild Strawberries to the reputation it now enjoys; as Cohen-Shalev continues, “Bergman let his director’s ego…be conquered by the expressive fecundity of Sjöstrom’s face.”2 Ultimately, Wild Strawberries is wholly dependent on the known real-world image of its star as a former industry powerhouse. Victor Sjöström the past filmmaker is contrasted starkly against Victor Sjöström the frail elderly man – he was known to smash his head against set upholstery with frustration when he forgot his lines – to imbue the film with far greater meaning.

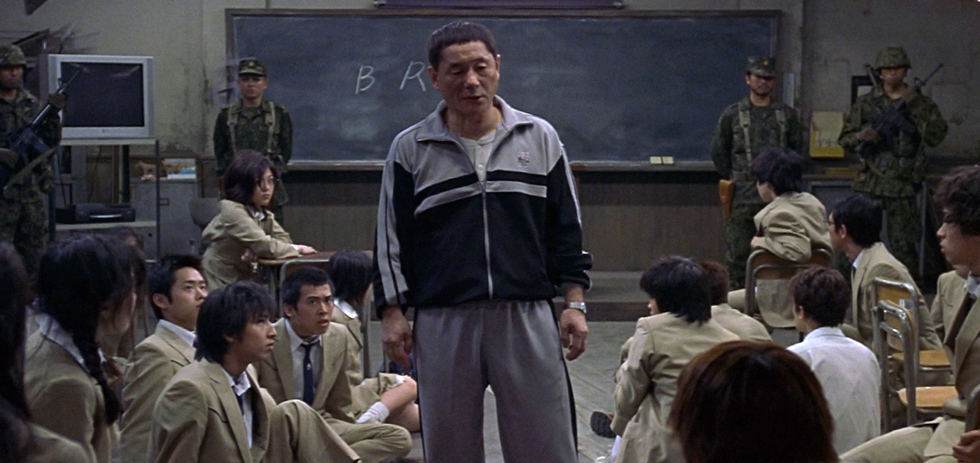

On a cheerier note, Wim Wenders – twenty-odd years later, after auteurism had gained major traction – took the concept of homage to its most extreme lengths in his Deutsch-noir The American Friend. A lean, adept retake of postwar US noir transposed to grimy ’70s Hamburg, and taking elements from several of the Patricia Highsmith novels which also spawned The Talented Mr. Ripley and Ripley’s Game, the film features well-known film directors in essentially all of its criminal roles. These span from Dennis Hopper, enfant terrible of New Hollywood, as Ripley, to then-newly-revered genre filmmakers Nicholas Ray and Sam Fuller as his associate and a mobster respectively. Wenders’ casting here could be seen as a gimmick, but is in truth inspired, as each of the director-stars seems to play a character from one of their own movies: Fuller bursting onto a train carriage with a trench coat and pistol, Ray swivelling in his chair threateningly, eyepatched and whiskied; even French New Wave moper Jean Eustache appears briefly, propping up a bar and looking morose. The ‘homage’ is taken to its extreme, functioning to pay tribute to not only each of the actors involved, but also to the noir genre as a whole, as well as acknowledging the stylistic and critical debts owed in both directions across the Atlantic. Honestly, the film’s only real weakness is that the various European non-actors trying to speak American slang English end up sounding a bit like an episode of ‘Allo ‘Allo, which can be forgiven in a project as innovative as Wenders’. His kind of homage has never been recreated since, but recent years have given us some sterling instances of director-casting in this category. It would be remiss not to mention Takeshi Kitano’s appearance in 2000’s Battle Royale, if only for the obvious glee with which he plays his role. Kitano is the teacher/maestro tasked with coaching the film’s schoolchildren about the island deathmatch they are about to be dropped into, in a clear nod to the bloodiness of his own films. The most enjoyable aspect of this homage is that Kitano’s public persona as the Japanese film scene’s resident renegade spills over into his performance; cruel and unusual bloodsport is probably what Takeshi gets up to at the weekend – he’s barely even acting.

THE MIRROR

Closely related to Wenders’ complex homage system, and probably the straight-up coolest version of the director-star phenomenon, is that kind of performance written, cast, and judged with the specific aim of reflexivity: commenting on something in the filmmaking process outside the realm of the film diegesis. Logically enough, most films in this category are films whose plot actually involves the film industry, intending to explore the issues that arise when creativity and economics are so unnaturally entwined – hence ‘the mirror’. Curiously enough, films of this sub-genre which lack the prestige to lure famed directors onto the screen tend to struggle, either ageing badly or relying on inside jokes and pastiches which become tiresome: Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful features a great douchebag performance from Kirk Douglas but is otherwise pretty forgettable, and recent ‘tortured artist’ fare hasn’t gone too much further than the lame 8 ½ homage Nine, whose main draw was managing to put Daniel Day Lewis and Fergie on the same bill without the universe imploding.

The most infamous ‘mirror’ of all, though, has to be Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, the striking 1950 noir with William Holden as a screenwriter becoming entangled with a faded film actress. The real all-but-forgotten silent film actress Gloria Swanson plays the former starlet in question, and her character Norma Desmond’s yearning for an unlikely comeback performance mimics the nature of Swanson’s appearance; Swanson herself was a massively popular early female film comedy star whose career, like so many others, had died with sound. The director-star in the piece, though, is the irascible and mysterious Erich von Stroheim – an Austrian émigré who habitually lied about his background to paint himself as an international playboy nobleman, Stroheim attained legendary status with his films about the basest elements of human desire, most notably Greed and Foolish Wives. He had also directed Swanson herself in Queen Kelly in 1929, a film that appears at one point in Sunset Boulevard. With Stroheim as Max the butler to Swanson’s tragic Desmond (a name itself a reference to a murdered Hollywood silent filmmaker), Wilder’s film takes on the appearance of a journey through the conventions of the noir genre deeper into real life movie mythology.

The real genius of Stroheim’s casting is that it plays off his existing persona not to pay homage, but instead to enhance the film’s themes of stardom and performance – Stroheim’s personal embellishment of his life story is matched and compounded by a film in which he plays another fictional version of himself; even in ‘real’ life, he was already one. A minor cameo in Sunset Boulevard provides a reference point to further ‘mirroring’ director performances: one of Desmond’s unnamed poker buddies, all in truth real figures from the ’20s film industry, is played by the slapstick star and director Buster Keaton, at the time wallowing unrecognised compared to his contemporary Charlie Chaplin. Thankfully, Keaton’s reputation has been deservedly restored these days. Chaplin actually cast his old rival, again unnamed, in his quasi-autobiographical late film Limelight. This kind of self-referential casting in especially rewarding for its warmth, and as a nod to committed film fans. Chaplin’s Limelight character, desperately in need of a stage partner to revive his act, calls on an ‘old friend.’ The whole sequence is a paean to the halcyon days of silent film comedy; as Buster remarks, in the pair’s dressing room: “if anyone else says it’s ‘just like the old days,’ I’ll jump out the window!” The pair’s classic and purposefully old-fashioned vaudeville performance recalls the hilarious acrobatics which both employed to entertain millions thirty-plus years before, and only viewers in the know are in the loop.

THE SELF-(AB)USE

Could I really write about film directors turning acting performances without mentioning Quentin Tarantino? Much-maligned for his gurning appearances in both his own films – a narratively superfluous turn in Pulp Fiction which existed only to allow Tarantino to say “nigger” on screen as many times as possible being the worst example – and those of his friends – as an uncomfortably on-the-nose sex criminal in buddy Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn – Tarantino has become the byword for indulgent cameos. There are other filmmakers, too, whose acting appearances appear cynical, either as cash-ins on their image or as episodes of forced mateyness. Alongside a directorial career in its way as innovative as Tarantino’s, Spike Jonze has made a series of baffling appearances – in the Jackass team’s tedious Bad Grandpa, in the David Cross TV vehicle The Increasingly Poor Decisions of Todd Margaret, in high-profile Oscar bait such as Moneyball and The Wolf of Wall Street – which seem calculated to scream “Look how all of us Hollywood types are just friends! We appear in each other’s movies as favours! I live next door to Dave Grohl!”

I would argue, though, that directors strategically casting themselves constitute a third category, not all of whose entries are as self-abusive as QT’s. On the other hand, self-casting – or even fraternal collaborative casting of the Jonze type – has been employed to enhance the sense of theatricality or self-awareness of a film; directors can draw on their pre-cultivated image in more meaningful ways. One of the most image-aware of all filmmakers, Orson Welles, cast himself in a unique impresario role in his staggering 1974 docufiction-come-sleight-of-hand F for Fake, narrating and appearing himself in a number of guises. Ostensibly a doco about legendary art forger Elmyr de Hory, the film sees Welles play himself as a kind of compere figure, delivering much of the narration to the audience in person, replete with smirking verbosity and his trademark baritone. Because it wouldn’t be Welles without some hugely impractical artistic decisions, most of this takes place on a train platform, or in Majorca, or in silhouette, for various obscure reasons. The real magic of Welles’ self-casting becomes apparent as F for Fake goes on – its production was disrupted by a real-life police hunt for de Hory and Welles’ wild relationship with his Croatian muse Oja Kodar (who appears in the film), and the biographer brought in to discuss de Hory turned out to be a hoaxer himself. All of this turmoil is inculcated into Welles’ presentation of himself, as he becomes more and more involved in the supposed topic of his documentary, appearing at parties with the famed forger, and telling a long tale about his lover Kodar’s supposed involvement in art fraud. One of the most famous posters for the film shows Welles’s face with the top half repeated and superimposed on his forehead; this is a film about layers of image, of meaning, of truth. While there’s an infinite amount more to F for Fake than even this – half of the above plot points turn out to be misdirection or outright fabrication – the way in which Welles invokes his own persona to turn his doco into a film about authenticity and performance remains one of the most effective ‘acting’ appearances by a director ever.

THE WILDCARD

Some things, of course, are not so easily categorised. The ‘wildcard’ appearances by film directors in others’ work comprise the unexpected, the bizarre, the absurd and the terrible, those acting turns baffling enough to make you check IMDb: “Was that really the same Nuri Bilge Ceylan? In an episode of 2 Broke Girls?!”3 The majority of these left-field appearances tend to be made by film directors unconcerned with maintaining a particular persona, either out of an ethic of independence or out of financial or career problems. It’s very tempting, for example, to place Alejandro Jodorowsky’s range of unheralded and largely unknown acting performances over the decade into the latter category: the Chilean responsible for such undefinable acid-fables as El Topo and The Holy Mountain putting in a turn as Beethoven in an obscure Italian film, a role as “Prophet” in a Spanish western still awaiting 5 IMDb votes, and playing sort-of-himself (“Jodo”) in a Bulgarian Euro-art film all seem to have been endeavours aiming to raise cash for The Dance of Reality, which was Jodorowsky’s first film in twenty-three years when it was finally released in 2013.4 Interestingly enough, the intervening years saw several documentaries, from 1994’s The Jodorowsky Constellation to the video shorts A Season of Jodorowsky in 2010, released about him, all in the context of Alejandro the film director. It would appear that a ‘director’ image outweighs an ‘actor’ image more or less in perpetuity when the two are opposed – adding the recent Jodorowsky’s Dune to the mix, the Chilean’s cult following seems to persist even when he is not a working film director, and even when he is explicitly making a living as an actor. His odd off-the-grid acting appearances seem to carry little weight with his fans.

On the other hand, there are filmmakers whose acting, even in totally unexpected projects, seems motivated by personality alone, and yet still garners its own following alongside their directorial output. David Lynch’s rare forays onto the screen my have begun in his own Twin Peaks, but have found an outlet in recent years in Seth MacFarlane’s range of animated TV comedies, appearing in The Cleveland Show and Family Guy. It’s harder to shrug off these roles as mere paychecks; Lynch is a successful enough director that he could turn to acting in more or less whatever he wanted. Alongside his varied and eccentric contributions to media culture in recent years,5 his animated appearances, as well as those in Louis C.K.’s self-titled sitcom and an upcoming lead role in his daughter Jennifer’s crime thriller A Fall from Grace, point to the hallmarks of a 21st-Century auteur: image awareness, media savvy and an artistic unpredictability employed to avoid Hollywood industry anonymity.

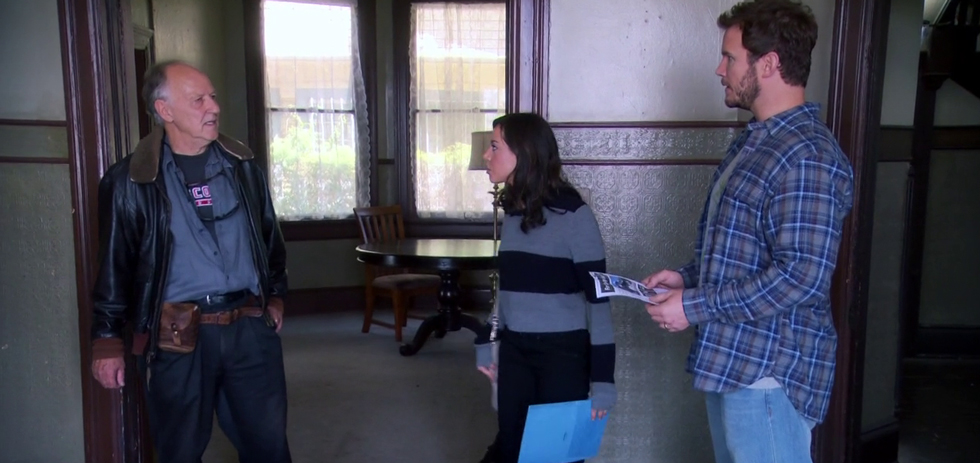

These qualities, almost predictably, are all embodied and inverted by Werner Herzog, the Teutonic lunatic, 4:3 favourite, and renowned chicken-despiser. All in all, there is probably no other figure in film history whose primary fame laid as a director, but who has made such an eclectic range of acting performances. From a skeletal face in the afterlife in the now-tasteless Robin Williams romantic drama What Dreams May Come to a Plastic Bag in Plastic Bag, Herzog’s acting has always – much like the ‘mirror’ category discussed earlier – in some ways played on features of himself, either real, manufactured or somewhere in between. Stroheim and Keaton never took on quite such bizarre roles, though. Herzog’s friendship with alt-Americana chronicler/professional weirdo Harmony Korine has led to several appearances in Korine’s films, most notable as the title character’s father in Julien Donkey-Boy. Herzog hosing down Ewen Bremner in an alleyway while admonishing him drily to “be a man” and “quit shifting around” may be one of the strangest images independent cinema has produced. Much like Lynch, he seems interested in the potential of television to compartmentalise his image, appearing in The Simpsons, as well as a recent role in Parks and Recreation. Some of his other appearances could fool you into believing Herzog was a jobbing character actor, appearing as the generic European baddie in the Tom Cruise career-death-throes flick Jack Reacher, real-life Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt in the most recent Heimat instalment, and “The German” in improv comedy The Grand.

It’s telling that even the most chaotic of director-star careers can reveal much about Herzog’s image, though. His seemingly random acting appearances in box-office cannon fodder, American independent film, and little-known German productions reflect a career predicated on the unexpected, the power of mythmaking, and the basic absurdity of the world. Other directors’ acting is usually easier to define: whether measured to pay tribute to their work, to build a public persona that can enhance their own films’ success, or just to slyly reference the subterranean world of film stardom, film directors looking back at the camera is universally fascinating.