In our regular column, Less Than (Five) Zero, we take a look at films that have received less than 50 logged watches on Letterboxd, aiming to discover hidden gems in independent and world cinema. This week Jeremy Elphick looks at film that falls outside of the Letterboxd database, George Gittoes’ The Miscreants of Taliwood.

Date Watched: 15 April, 2015

Letterboxd Views (at the time of viewing): 0

There’s ‘Less Than Five Zero’ and then there’s another category, one we haven’t covered in this segment before, “zero”: when a film hasn’t even been registered in the Letterboxd catalogue. Oddly enough, this is the case with the entirety of filmmaker George Gittoes’ oeuvre. Despite beginning his career in the art world, Gittoes quickly expanded his work into documentary-making. In his art, Gittoes is aesthetically experimental, but heavily influenced by social realism.1 His approach to cinema mediates a similar position between established techniques and deconstruction.

Gittoes is comical, jocular, and continually leaving his audience in awe as he navigates and assesses many of the most dangerous war zones on the planet with a disconcertingly casual stride. At the same time, his insights are always commanding and confronting; the contrasts he draws between his humanist-driven encounters and the more startling horrors he places alongside them creates a rich, nuanced and necessary presentation of places that very rarely receive such. For what it is, The Miscreants of Taliwood is a radically underseen film. In my opinion, it’s the best film Gittoes has made.

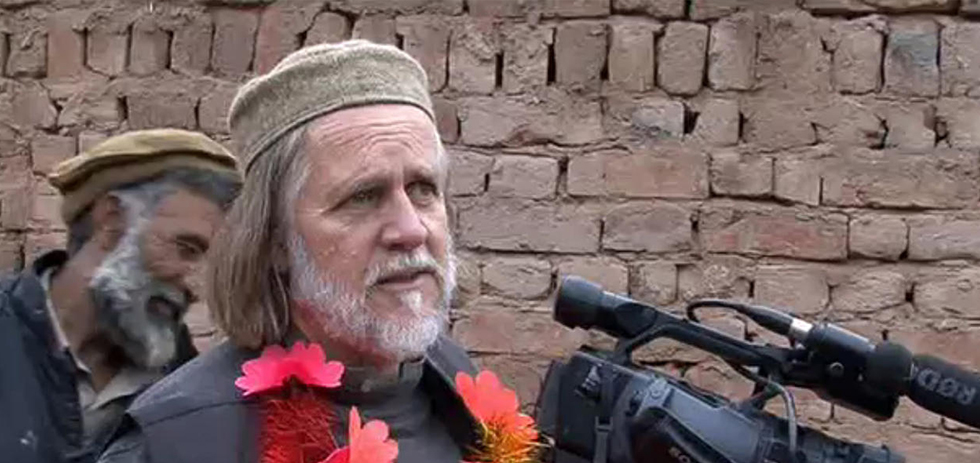

The Miscreants of Taliwood revolves loosely around the film industry in Pakistan in the mid-2000s as the Taliban’s anti-entertainment campaign is beginning to intensify. It’s established fairly early that money is flooding out of the industry and the idea of funding anymore films is unlikely. Gittoes decides that he has the funds – around $3,000 – to make a Pashto telie film2 with the biggest stars of the genre; Javed Musazai, a prominent actor in the scene, takes centre stage. Musazai is a towering figure, has dark red hair, and brings one of the most optimistic and continually invigorating presences to the documentary. He plays a typical hero in the film Gittoes goes on to produce, where the latter stars as some sort of villain. When they’re not filming, Musazai is raising a family upwards of twenty people as a far less enigmatic and far more a hard-working and dedicated father. Seeing a lot of the figures in the film transitioning between the film being made and the documentary itself is fascinating and revealing towards the essence of a lot of their characters, but this approach to filming Gittoes has taken simultaneously allows the film to take blur between reality and fiction; later giving the filmmaker’s insights a unique breadth and sense of conviction.

Gittoes has said that Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing borrows a certain style from his works 3 and in The Miscreants of Taliwood it’s easy to see what he’s talking about. The interplay between reality and fiction is fiercely articulated by Gittoes in an intricate and controlled mess; the two bleeding in and out of each other in a way that places the audience and their perception in a perpetual state of uncertainty throughout the course of the film.

One of the most continually startling aspects of Gittoes film – and something that has punctuated his entire career as an artist – is his proximity to an ever-present danger and unrest. Throughout the film, there are countless deaths which become a numbed and normalised tragedy towards the end of the film. The time Gittoes is filming is particularly poignant as well. One afternoon while his crew are filming, Benazhir Bhutto is killed. Rather than filming fiction that day, they’re within the community, documenting this palpable sense of total loss and absolute pain. Bhutto’s assassination is shocking, even almost a decade since it happened, however, the expressions and reactions Gittoes captures give the aforementioned tragedy a powerful a sense of permanence.

Structurally, the film is complex; it’s cut in such a detailed way – with far more changes than your average documentary – that it never slows down as a film. “They’re all cut like MTV” 4, Gittoes asserted about his documentaries, however, MTV isn’t covering anything in the same league as Gittoes in terms of pressure, danger, conflict and chaos. For Gittoes to appropriate such an approach to editing is brave, but somehow it works out – most likely, because Miscreants is precisely that: an incredibly self-assured film that finds itself enveloped in stylistic risks.

The Miscreants of Taliwood finds its climax in what is referred to as “the Grey Mosque scene”, where Gittoes and his crew stumble upon a suicide bombing of a Mosque where everyone is killed. Like most of the film, it’s graphic and more so: it’s present. Nothing about the movie is reflective, it’s a perpetual and immediate danger and fear of the present that Gittoes records. The Grey Mosque bombing isn’t something Gittoes was able to predict as a filmmaker, and it’s not something he captures in retrospect. It is, however, arguably the most powerful piece of footage Gittoes has shot. As a documentary maker who has focused on zones of conflict for his entire career, that isn’t a light statement to make.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, Gittoes stands amongst the remains – visibly shaken, deeply sad, and struggling to speak amidst the vastness of the tragedy he has found himself surrounded by – and interacts with the other people witnessing in the aftermath. This is a community Gittoes has become intensely close with throughout the filming of the documentary. Seeing them having fun making a movie is one thing, but seeing them grieving so intensely – holding one another silently, crying, looking blankly at the ruins – minutes is a collage of pain that few other documentaries have articulated. One man – who has just seen the death of three of his close relatives – directs the camera crew through the Mosque in a state of stark disbelief punctuated by an intangible pain that consumes the scene. He points to blood and the camera follows. He prays and cries in front of the shoes of children – removed for prayer – that were killed while they were in prayer. This again, is never reflective; it is a recording of a moment of abject pain for the subjects – and even now, years since the event itself, and through multiple barriers of disconnection from it – it remains one of the most affecting pieces of cinema I’ve witnessed.

Unlike his more recent venture, Love City Jalalabad, The Miscreants is a much darker film. There’s these aforementioned bombings and decapitations amid violent encounters with the Taliban all tightly wrapped in a sheet of very real and confronting violence. Yet, somehow, Gittoes makes a great amount of the film funny. There’s comedy woven in amidst the horrors he encounters. More important, perhaps, this humour never feels like its trivialising the documentary or its subjects. In an almost inexplicable way it feels like its necessary in such an overtly dark film, and it feels like it makes an the final product that Gittoes released a more wholesome, confronting and shattering piece.

I interviewed George last year and the idea of comedy within these documentaries came up as a point of discussion and his reasoning behind the inclusion of these “gags” gave the strongest insight into his approach to cinema. It’s a simple dictum to Gittoes: “take out as many serious stories as you like but don’t lose a single gag – because comedy is so hard to achieve and it’s just so good, you know? In all my experiences of war, what sees people through the worst horror is our human ability to laugh and to see the comic in things, and that’s it.” The way in which Gittoes mediates between human tragedy and lighter comedy is intricate, careful and respectful. It’s makes his documentaries amongst the strongest in the genre. Gittoes is an incredibly brave and persistent filmmaker, but his relationships with his subjects and the areas he films are perhaps the key to the documentaries that have resulted from this approach. Gittoes film work is dramatically under seen and now is a better time than any to change this.5 The Miscreants of Taliwood is the place to start.