Alex Garland has made a name for himself as a screenwriter who takes an intelligent approach to genre concepts. Often only billed as “the writer of 28 Days Later“, Garland has done some fantastic work in actually subverting genre elements or suddenly lurching into a different genre entirely, as in his novel The Beach, the screenplay for Sunshine, and arguably even the last half-hour of 28 Days Later. His directorial debut, though, the artificial intelligence-focused Ex Machina, is something of a misstep; lacking any real narrative inventiveness, it telegraphs its twists far in advance and is packed with well-worn thematic concerns regarding identity and existence, scenes playing out with a dull faux-technical approach to the questions of life and love.

Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson), a young programmer at Google stand-in BlueBook, wins a company lottery and is given the opportunity to spend a week with Nathan (Oscar Isaac), the reclusive founder of the company, who is at work on a top secret project, which turns out to be the development of a sentient robot, Eva (Alicia Vikander). Though the film opens with a refreshingly minimalist piece of exposition (a dialogue free opening five minutes helps), it soon finds itself determined to overexplain things to the audience. For the benefit of the viewer, Caleb explains to the head of the world’s biggest technology company what the Turing test is – whether an A.I. can pass off as human to a human – and whilst that piece of exposition might be necessary for the plot (it’s the only reason Caleb is there in the first place), it feels so artificially delivered (ha!), as do many pieces of exposition all throughout Ex Machina. We get a string of hyper-technical terms from Caleb in a few scenes, only to have Nathan cut him off and ask for simple answers, an infuriatingly silly piece of writing that passes off simplicity as a clearer focus (once more tied up in an overly obvious scheme of misdirection), when in fact all it does is make clear Garland wants to hold the viewer’s hand through what is, ultimately, a very simple piece of science fiction.1

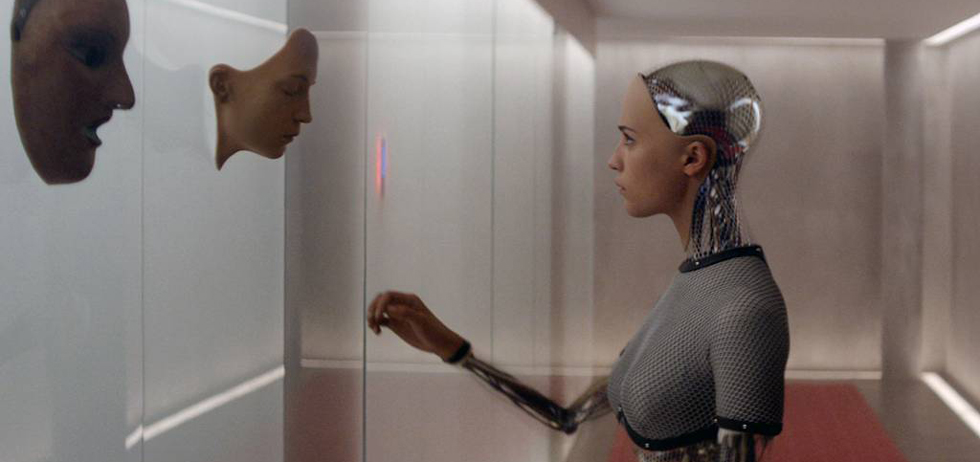

Structurally the film is broken up into ‘sessions’, wherein Caleb interviews Eva in an attempt to find proof of her humanity.2 These interviews run from compelling (the first hint that something is awry is pretty bracing) to a watered down Under the Skin riff, where Eva puts on a dress and whirls around for Caleb in an attempt to blur the line between android and human as much visually as theoretically. What’s worse, though, is what surrounds these interviews; the scenes in which Caleb and Nathan analyse that day’s work are a tedious collection of trite duologues on topics ranging from sexuality to personal insecurity to self-awareness. Because the general thrust of the plot is so obvious, these explanatory scenes do less to build tension than halt the pace altogether for a neat recap of related conceptual ideas.3

Not content to merely make a film about the ethics of artificial intelligence, Garland’s script also makes a failed attempt at incorporating modern concerns through clumsily shoehorning in alarmism regarding surveillance and the power of Google. It all amounts to post-Snowden hysteria played off with a winking nod to the audience, who apparently don’t know what the Turing test is but will definitely swallow the idea that a near-flawless incarnation of human memory and thinking can be neatly captured and summarised through our search history.4

In Garland’s earlier work he has shown an adept handling of character, particularly with either small casts (Never Let Me Go, 28 Days Later) or with a larger group interacting in an enclosed or restricted space (Sunshine, The Beach). With that in mind, it would be hard to conceive of an audience conduit less interesting than Gleeson’s Caleb, wholly bland of personality, and whose only unexpected moment of emotionally charged dialogue comes in the form of a lazily packaged reveal about his family life.5 In fact, it’s lazy in more than one way. Firstly, it’s the only real personal piece of information we get about him (and it’s a blatant attempt at audience sympathy), and secondly, because it feels so sudden and specific it seems like it has to be constructed as part of a plot point later on, something that tends to happen time and time again in Ex Machina.6 Vikander does a fine job with what she’s given, though she’s not a shade on Scarlett Johansson’s disembodied voice in Her (then again, who is?) nor her own turn in Lisa Langseth’s recent Hotell. Isaac is the best performance in the film, at least for its first half, managing to string along this potent undercurrent of menace even amidst the broad characterisation of a destructive alcoholic.7

The cinematography is mostly uninteresting, shiny hallways and lush landscape shots punctuated only by sudden jolts of red lighting that amount to very little other than setting up the unfulfilled expectation of a thrilling and perhaps horrifying final stretch as per Sunshine. The set design and usage of limited external photography is reminiscent of another Brit-directed bottle sci-fi, Duncan Jones’ Moon, whose central mystery, though a touch obvious, was still able to work because of a strong bond between audience and character. As I wrote in my review for The One I Love, we’ve been spoiled for small-scale character-driven science fiction by Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror, and though his own AI episode, “Be Right Back” (starring Gleeson as an AI himself), is one of the series’ weakest, it still has a vastly more engaging sense of love, human interaction and intelligent mimicry than Ex Machina, whose pointed (and yes, telegraphed) Verhoeven-esque climax does little to make its take on femininity and the male gaze anything more than a cursory glance.

Unlike Eva, in her seemingly complex and nuanced artificiality and mimicry, Ex Machina is little more than an uninteresting facsimile of ‘ideas driven’ science fiction from a writer who is far better than the script he’s delivered here. Its human characters are as hollow as Eva’s chasis and its lack of a genuinely surprising plot make the film feel merely like an overlong short, or a test run for something else. Perhaps watching Ex Machina is a Turing test for the viewer; if we’re presented with robots, a confined space, an awareness of the modern surveillance panic, and three good actors, will we fall for thinking that this is a decent science-fiction film?

Around the Staff:

| Felix Hubble | |

| Matilda Surtees | |

| Jessica Ellicott |