It’s a difficult task to reduce any artist’s lifework to a two hour movie, and a singular icon like Pier Paolo Pasolini on paper would make the very concept of biopic film seem inadequate. Accomplished as a film director, author, poet, critic and public intellectual, and a polarising figure in his native Italy due to his sexuality and radical politics, to say nothing of his provocative cinema, exactly how you do justice to such a figure does not seem particularly intuitive. Refreshing then, that Abel Ferrara and Willem Dafoe’s tribute to the legendary auteur takes a novel approach compared to the route of overstuffed dramatization – Pasolini is a very trim, pared-down film, narrow in content but broad in scope. Much like the life it celebrates, one only wishes the 84-minute film wasn’t over so soon.

The film follows the last few days of Pasolini’s life – we see him with his mother, dining with friends, reviewing scenes from Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom in relation to the notorious film’s battle with censorship, before a lengthy media interview outlining some of his key philosophies; though clearly articulate, he requests to stop the interview and continue on paper, more confident in his ability to express himself in writing than orally. Of key interest to fans will be the scenes imagining the realisation of the unfinished script Pasolini was working on before his death. An allegoric journey of sorts, it looks like a version of the Toto-Ninetto Davoli connection he utilised in films like The Hawks and the Sparrows and his segments from anthology films Le Streghe and Capricco all’italiana, discovering a mythical annual orgy between gays and lesbians in order to repopulate the world. Like any Pasolini film, the premise sounds goofy on paper, but Ferrara stages these scenes with a sense of awe and satire reminiscent of the master’s best works. Finally, Ferrara’s film ends with Pasolini’s death. The treatment of it will raise some eyebrows, but reads as a marker of discretion in line with the film’s wider intent rather than any sort of indulgent hypothesis to one of cinema’s enduring real-life mysteries.

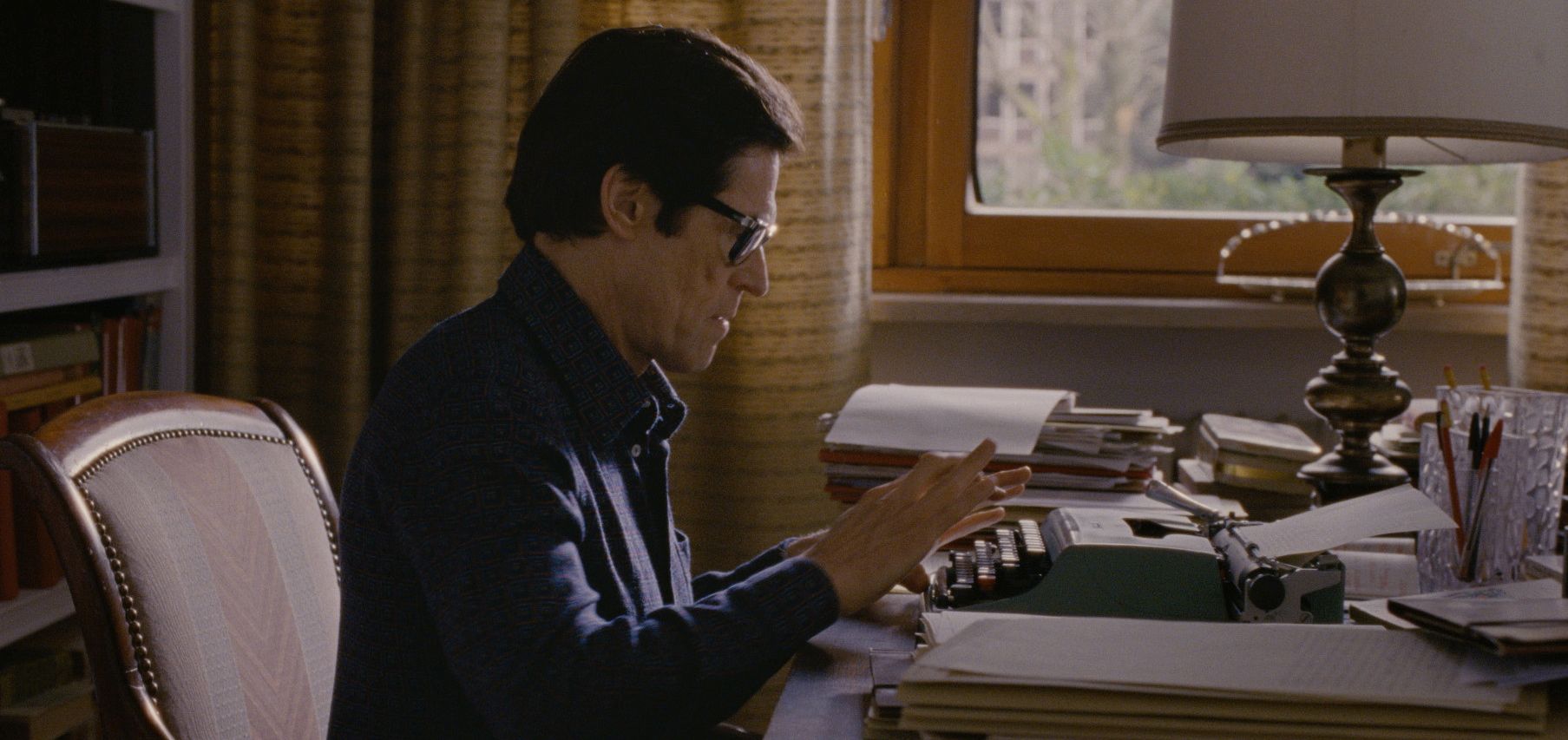

At the centre of it all is Willem Dafoe as the titular artist, in his third collaboration with Ferrara after Go Go Tales and 4:44: The Last Day on Earth (their fourth film, Siberia, is currently being crowdfunded), and he slips into the character effortlessly – though in this instance such a descriptor undermines the clear research and preparation he clearly undertook before filming – relying not just on his staggering resemblance to the director, but embodying him wholly. Every gesture speaks volumes, as a man of great intellect and introspection – in the aforementioned interview segment, we don’t just perceive a character reciting lines, but the actual act of struggling to articulate his scattered but considered thought processes and funnel them into plain language as best he can. Much has been made of the fact that Dafoe wore actual clothes of Pasolini’s, a Visconti-esque length toward historical accuracy, but it works well as allegory for the performance. Dafoe doesn’t just wear his clothes but his thoughts, ideas, expressions; getting into his skin in one of the finest performances of the year.

Ferrara’s treatment of the material is particularly lucid, opting for darker tones and evoking a sombre mood in the lead up to his death. The expressive use of shadows and darkness throughout offers an elegiac, dreamlike quality as the editing rolls back and forth between scenes, dramatizations of the his literature and films, reinforcing that Pasolini’s life and films were inextricable from one another, unfolding like a poem or tapestry rather than an Oscar-ready biopic. The only stylistic choice that strikes as odd is the inconsistent use of language, opting for large parts in English. As such an accomplished poet and writer in both the Italian language and gritty dialects that was so vital to his work, this does seem like a false note, and a strange commercial concession if it is one, considering its mostly Italian production and limited distribution prospects outside of the Festival circuit.

The only other gripe some might have with the film is the level of presumed knowledge – as tribute to an artist, it will be of limited value to those unfamiliar with Pasolini’s life work as it doesn’t stoop to exposition of the various controversies and paradoxes in the man’s life, and even those familiar may find themselves lacking some contextual information – an off hand reference to his association with Hungarian director Miklos Jancso, for example, went over this reviewer’s head. The casting of Ninetto Davoli, Pasolini’s longtime lover and collaborator, also adds a emotional pull to the film that casual viewers may miss. But similarly, the film succeeds in its own integrity toward its subject matter, ignoring the artist’s base instincts with material as loaded as this and refusing to tie Pasolini’s life to digestible narratives. His death isn’t a culmination or thematic endpoint for earlier issues, despite being ripe for an JFK/Costa-Gavras type conspiracy thriller. In the short few hours of Pasolini’s life that we are witness to, we gain insight to his philosophies, his films, his writing. But as someone prone to narratives in film history, the treatment of him is refreshing. The moving final scenes of the film capture his grieving friends and family, bringing a simple truth that the wealth of scholarship on the director loses sight of. This was a man whose life, regardless of his extraordinary art, mattered to those around him, and whose senseless death was a private tragedy and not a symbolic token. Pasolini is a fleeting, frequently stunning and textured look at an incredible life

Around the Staff

| Virat Nehru | |

| Luke Goodsell | |

| Ivan Cerecina |