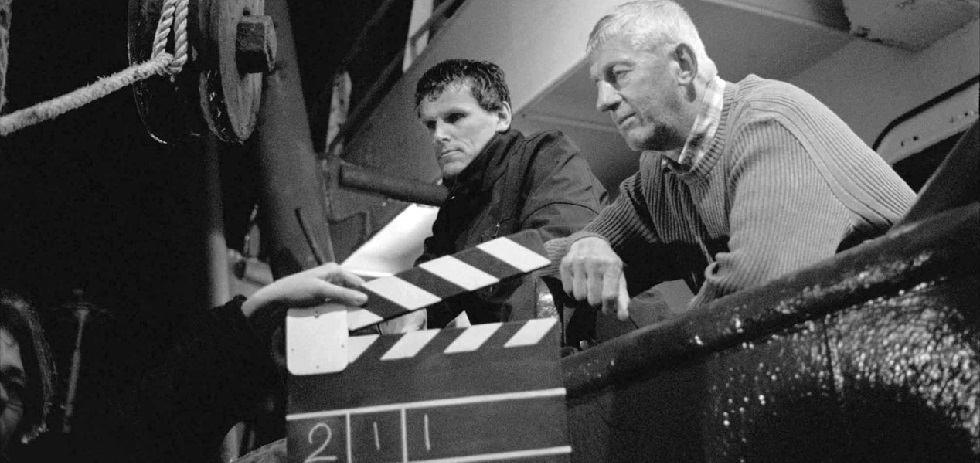

The debut feature-length documentary from Siebren de Haan and Lonnie van Brummelen, Episode of the Sea, traces the historic practices of the North Sea fishermen of Urk as they document their shrinking role in an increasingly competitive market.1 Whilst, perhaps clearly, the tale itself is far more intriguing on screen than what the synopsis might suggest, the film’s major strength lies is its conflation of the decline of the Urkish fishing tradition and the death of celluloid cinema. Shot with a 4:3 aspect ratio on obsolete equipment which was manufactured in the 1980s, using a few different film stocks (including the last known batch of some ancient Kodak celluloid), Episode of the Sea marries staged (and real) vignettes with terse, non-narrated archival-seeming footage.2 It’s an apt way to construct such an abstract and unique documentary, one that becomes more of a rumination on a sort-of controlled entropy rather than pushing any narrative story line, although the execution of the film’s narrative elements are impressive as well.

Using a series of staged and fictionalized vignettes, non-narrated static documentary shots, and scrolling didactic title-cards, the film cleverly straddles the line between documentary and fiction, as Michael Winterbottom’s The Road To Guantanamo and Caveh Zahedi’s I Am a Sex Addict have done before it. de Haan and van Brummelen were sent on assignment to document the Urkish community, an assignment that lost its funding almost as soon as it commenced. Unsure what to do they carried on, despite feeling like outsiders in the community, one that still holds onto its native Urkers tongue rather than speaking Dutch. After striking up conversation with the fisherman, they began to see parallels between themselves and the Urkish community. These parallels come to form the basis of the documentary and through them Episode of the Sea slowly progresses beyond traditional documentary fodder, transforming into a rumination on the decline of obsolete practices more broadly. As such, the film is less of a tale of an increasingly industrialized and competitive North Sea fishing industry than a tale of the death of a historical practice.3

Episode of the Sea feels somehow more sophisticated than other documentaries of its ilk; its 60 minute runtime and 4:3 aspect ratio may suggest that Episode of the Sea has been edited for television but its formal elements are far more sophisticated than that. The use of obsolete equipment and film stock, and aping of the dramatic theatrical tradition to convey its message are an ingenious way to formally reflect the parallel plot-lines of the death of celluloid and the decline of the Urkish fishing tradition. The focus on a community so resistant to change, with the odds stacked against them despite being at the forefront of technological innovation just a century prior perfectly reflects the state of the celluloid-focused film industry in its current climate. It’s surprising that de Haan and van Brummelen have crafted such an interesting tale of the death of the celluloid film industry given their relatively small list of credits, though perhaps such a tale need be tackled with fresh eyes to be fully effective. In this vein, there’s no indication of a stasis in a certain mode, the filmmakers’ relative lack of career makes their assessment of film a surprising and compelling one, free from any real anger or vitriol.

On a whole, Episode of the Sea is definitely worth seeking out, although it feels unlikely to have a long life outside of the festival circuit. The film perfectly encapsulates the decline of industry in the face of change and has a far more subtle delivery than venom-filled diatribes that can result from those who feel their mode of function is under threat. In contrast, Episode of the Sea feels more like a eulogy, a love letter of practices past that accepts the need for innovation and progression but laments the loss of the beautiful and unique aspects of tradition that are lost in such a transition. In this respect, Episode of the Sea is far more important than its humble points of reference may suggest.