The Kid Stakes, a Sydney-set feature from 1927, was rediscovered and then screened by members of the Sydney University Film Group in the early 1950s. The Kid Stakes will be presented in its re-mastered digital format for members of the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (the industry) and members of the partner body, the Australian Film Institute (the cineasts) in Sydney on the 10th of August this year.

1953: it was an early morning session at the News-Luxe on Pitt St in Sydney.1 The images in the two-reel comedy we’d just seen had been stunning, as was the realization that this old film mattered. Stumbling out into the foyer with me was another member of Sydney University Film Group (SUFG), Neil MacPhillamy. In that moment, an implicit pact was formed.2

The manager of that most lively of the newsreel cinemas was Phil Jones, a showman from a show business family. One afternoon we went in a creaking lift up to the rooftop of City Tattersalls Club where Gerald D. Tayler had his bunker of much ancient and some recent (but obscure) nitrate celluloid. That two-reeler we’d seen had been lifted from the best parts of a couple of prints that revealed itself to us as the 1927 Sydney-set feature film, The Kid Stakes, based on the still extant and popular Fatty Finn comic strip.

SUFG swung into starry-eyed action. Founded in 1947 as an offshoot of the Sydney University Visual Arts Society (in effect, arts and architecture students), the Group was as much about the mystique of cinema art as the S.U. Film Society (mainly engineering students) was about coaxing and tinkering with the projectors in the old Union Hall. In its first few years Group membership had been lifted by a series of acquisitional coups with rare films like The Queen of Spades, Riefenstahl’s Olympia and Carne’s thought-lost Le Jour Se Leve. The Group had spirit and energy in addition to some mighty organizing and promotional skills.

A law student obtained old Mr Tayler’s signature releasing the tea-boxes of film lengths. Medical student John Jackson Morris, also smitten by the film at that News-Luxe show, took over the Raycophone projector in the kitchen of the treasurer of Sydney Scientific Film Society, Jack Kennedy. They stuck the bits together as seemed sensible, since nobody had actually recorded how the excerpting had been done.

The projectionist of News-Luxe, Ron Israel, had made the front of house display by blowing up images from the frames of the old film itself.3 In the 8×10 form, they were planted around Sydney’s several (then) newspapers and in magazines like Pix and Australian Monthly. John Burke, the committee member with a camera, roamed Woolloomooloo and Potts Point for contemporary comparisons. Some surprised now-adult members of the cast found themselves standing on stage for the smash opening night. The film’s innocent comic verve and clever social insights, along with views of old Sydney, delighted two further nights of the gown and town audiences, even if the 1.33 images looked askew in the 1.37 gates.

Clearly, the film had to be preserved, something unheard of at that time. The Group now had the cash to pay for a 35mm negative to be duped off at Automatic Film Lab in Dowling St. Everyone just knew that the film should go to Canberra, where the National Library already carried documentary films, had begun getting silent classics for the country’s burgeoning film society movement and was understood to be concerned with preserving Australian films. But just what would the Library do with The Kid Stakes? Would other groups be able to see this wonderful old charmer of quintessential Sydney?

Frustrated as time passed, SUFG seized the conclusion of a tour by Mary Field, a British specialist in children’s films, to pop a 16mm print in her bag. Under the threat that the negative would also be shipped to the National Film Library in London, Canberra finally came through with an acceptance telegram. The film was safe and SUFG was off the hook.

These days, the catalogue of the National Film and Sound Archive lists nine versions and formats of The Kid Stakes. Some have many subsidiary copies. There is generous excerpting in Forgotten Cinema, the 1967 call-to-arms film by Anthony Buckley and Bill Peach. Prints have been sent to film festivals and special seasons around the world over the past forty years. A clip opened the Sydney office of the NFSA in 1986. Asked years ago by Macca on national breakfast radio, “What’s your favourite among them all”, the director of the Archive named, yes, The Kid Stakes.4

One further manifestation has emerged as the digital future of film comes rushing in. The NFSA has re-mastered that original celluloid print into a Digital Cinema Package (DCP) for showing in present-day cinemas. Having seen this copy, I can say that the flavour of the picture remains intense, with the beautifully naturalistic lighting and some little traces of cinematic wear-and-tear. As it romps along, there is barely time to take in the duality in its creation: skit business inventing, joke writing and performance eliciting by Tal Ordell, credited as writer-director, and the less-is-more perfection of camerawork and (presumably) editing by Arthur Higgins, credited on the same panel as cinematographer.5 A stage and radio man, Ordell only directed this one film, while Higgins was a life-long top cine-professional. They must have liked each other: the film sings.

David Donaldson was a president of Sydney University Film Group, the first director of the Sydney Film Festival and an inaugural board member of the Australian Film Institute. Now living in Adelaide after a career in adult education, he has been an inveterate campaigner and presenter for “films that matter”.

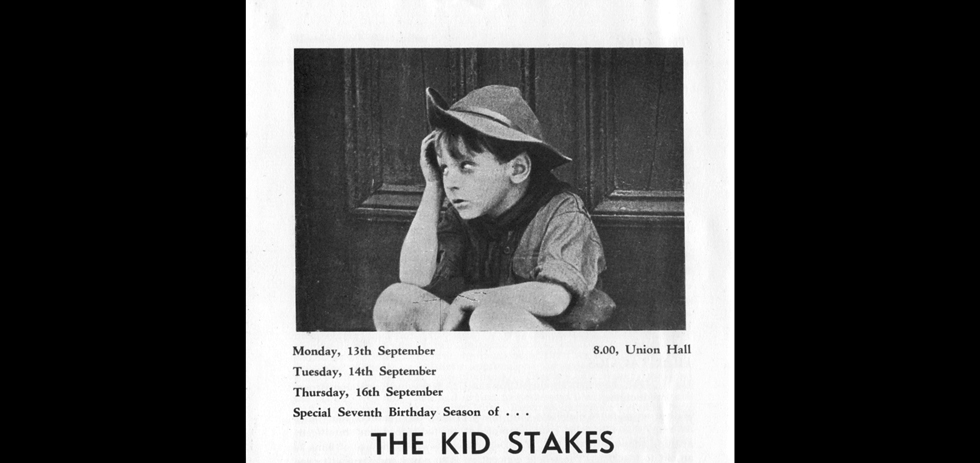

Below we have reprinted the text of the original SUFG program for the screenings of The Kid Stakes. A scanned image of this program can be found here.

THE KID STAKES

Australia, 1927. 85 mins. Silent.

Produced by Ordell-Coyle, Director: Tal Ordell.

Script: Tal Ordell and Syd Nicholls. Photography: Arthur Higgins.

To celebrate our seventh birthday we are proud to be able to show this wonderful Australian film. Two years ago the Film Group discovered it and included it in the International Film Festival. Six months later the only existing prints were cut to make a twenty-minute version for the newsreels. Last term the committee of the Group decided that it would take all necessary action to ensure that the film is preserved in its original condition, and so one of the committee set about reconstructing the print.

When this was done, and with the kind permission of the owner, Mr. Tayler, of National Films, we had a negative made. As there is no film archive established in Australia, this negative will be stored in London at the National Film Library.

The purpose of these three screenings is to help pay the cost of this negative and also to make a 16 mm. print which can be loaned to the British Film Institute and the Museum of Modem Art in New York.

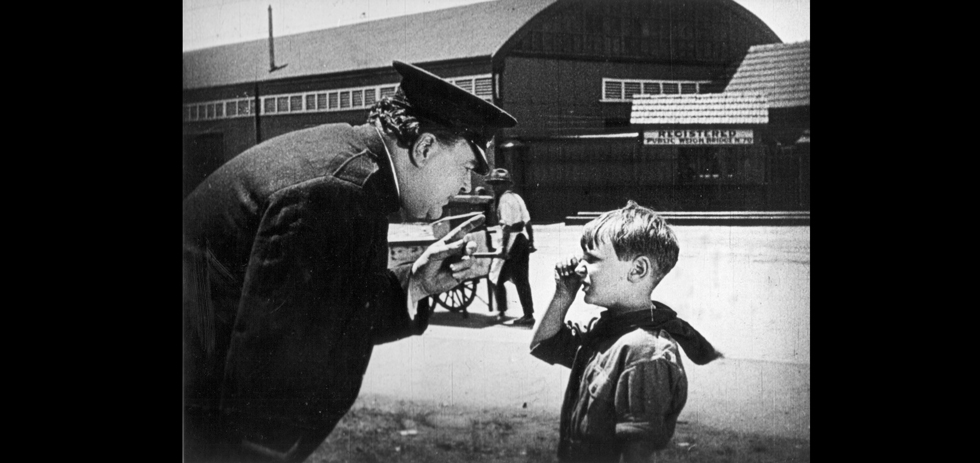

Said to be the last Australian silent feature made, THE KID STAKES concerns Fatty Finn and his gang. They are preparing to enter their pet goat, Hector, in the goat-cart race, but a member of a rival gang lets. Hector escape on the very morning of the race. The adventure of Fatty and the gang in their attempt to rescue Hector are told with real humour and a great deal of charm.

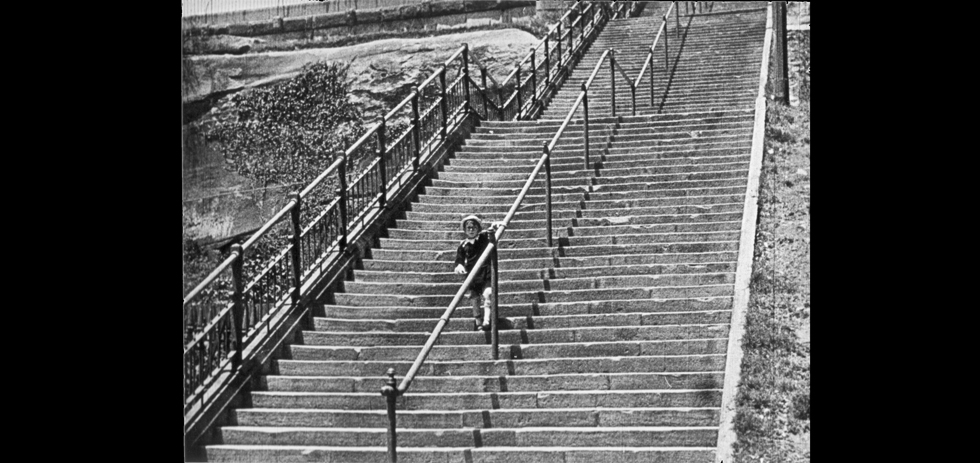

The action, which is nearly all photographed around Woolloomooloo, leads the gang up the well-known McElhone Stairs into the garden of a large Potts Point home where Hector has been imprisoned.

Throughout the film the photography is of a remarkably high standard. Although there is not one interior shot in the entire film, the quality of the images is never harsh and the movement of the camera, especially in the final race sequence, is very advanced. ‘When THE KID STAKES is compared with another film made at the same time, say SECRETS OF THE SOUL, it is surprising how very modern the Australian one seems. Perhaps it is because the cast consists mainly of children that the acting seems so fresh.

The humour in THE KID STAKES falls into two main types. Firstly, the chases, deceptions and escapades traditional to slapstick, but because the characters are built up so well, the comedy never leaves the personal level to descend to mere mechanics. There is also a strong flavour of satire running right through the film. The gangs that meet by the wharves, the double-crossings and betrayals and the threats are all mocking the gangster era that was then in full swing. Other contemporary fashions are satirised, the aviator-hero, the popular Romeo and Juliet type romance and the A.B.C.

As a piece of Australiana, with the clothes, customs, jokes and appearances of another era, the film is a valuable historical record.