Amy Berg beat Alex Gibney to the punch with her 2006 documentary Deliver Us From Evil, which looked at child sex abuse in the Catholic Church. Gibney’s 2012 Mea Maxima Culpa treads similar ground, and only a few years after that film, it seems like the interests of both filmmakers have once more aligned. Comparisons from Berg’s Prophet’s Prey to Gibney’s Scientology exposé Going Clear can easily be drawn: both documentaries follow rampant abuse and corruption within religious institutions, tying some of their faults to an American system that allows such organisations to flourish. The differences, though, are more potent; where Gibney’s film was a richly layered and oft-witty examination of religion and public perception of it, Prophet’s Prey is alarmingly conventional and one-note, feeling almost like a shallow online addendum to the book on which it is based.

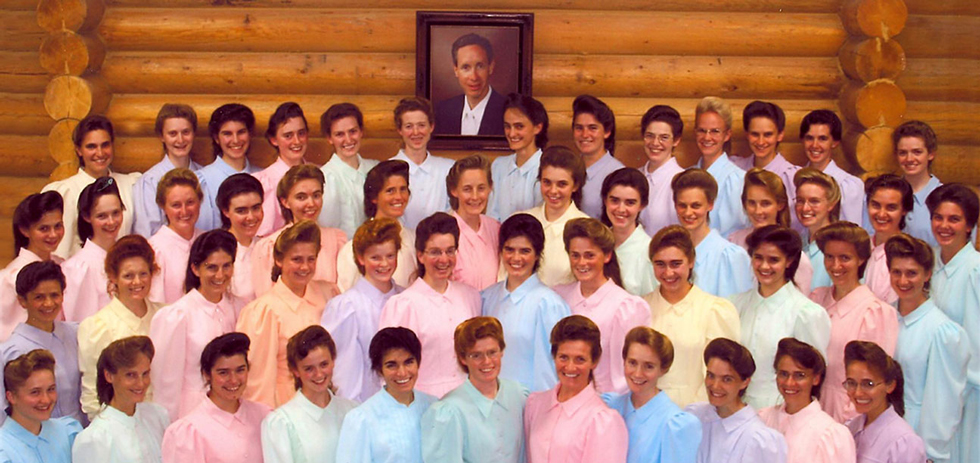

The religious group targeted here is a fundamentalist offshoot of the Mormon Church, whose primary belief is in the righteousness of polygamy. Located in Utah and led by the Jeffs family, the church thrives on isolation and the indoctrination of the children in the community. When the church was taken over by Warren Jeffs after the sudden death of his father, though, child marriages increased and Jeffs himself sexually abused countless children, including some in his own family.

Berg presents this story through a past tense journalistic frame; talking head interviews with those involved serve only to bolster the existing reporting on the church by private investigator Sam Brewer (the author of Prophet’s Prey) and writer Jon Krakauer. This approach is partly why the film feels so uncinematic and, perhaps, even unnecessary. Berg shoots Krakauer getting into a plane and flying over the church base in Texas only so his anecdote about flying over the base years ago has some visual accompaniment. Berg shoots the pair re-interviewing people that they’ve already spoken to in the course of their investigations, a clumsy re-do for the camera. Since Jeffs is already in prison, the primary focus of the documentary is awareness, but structurally it’s told to us as if it’s a pressing current investigation. Where visually Berg’s presence in the car with the men as they drive through one of the Mormon communities might seem almost Poitras-esque, it’s so far removed from that active danger and discovery so as to be merely perfunctory. Without any unique approach to documentary form, Berg’s film is just a CliffNotes for people who haven’t read the book.

A lot of the problems with the film come down to certain editing decisions. In order to more clearly convey the predatory nature of Warren Jeffs, there are some stunningly lazy tonal ploys; one recurring device is footage of Jeffs pleading the fifth in police questioning, as if it’s any more impactful the fourth time around. Even worse than that, Berg plays recordings of Jeffs’ religious proclamations over the sound of a choir of children; this would have been on the nose early in the film, but doing it after it’s been made immeasurably clear he preys on children is far worse, the blunt hammering home of the horror almost amateurish. The cinematography is just as bad: when Brewer is describing the schools in which the children were taught, the camera swoops through abandoned classrooms; the shots of children from the church playing on swings, captured by the camera lens, in and of itself feels invasive.

This occasional sensationalism is both in poor taste and, eventually, ethically dubious. Not even halting to consider the ethical issues with playing an audio tape of child rape in a documentary, perhaps a la Herzog’s internal dilemma in Grizzly Man, Berg has Brewer describe it as one of the most horrifying things you could ever listen to, then moves on to the court trials more broadly, before suddenly cutting to black and playing the short tape. It’s an easy way to make the audience uncomfortable, but it’s also not needed – Jeffs had been convicted and the documentary is packed with testimony alleging his guilt, yet the tape is played after all of this this. It’s cheap shock value masquerading as socially conscious filmmaking.

Whilst Prophet’s Prey clearly aims to fight for justice for a select group of victims of child sex abuse, it does so in such a lazy and uncompelling manner as to undermine the importance of its select issue.

Around the Staff

| Felix Hubble | |

| Lyndsey Geer |