The Melbourne International Film Festival are screening a series of experimental films this year in a program called Vertical Cinema, commissioned by the Sonic Acts festival. Ten shorts will be screened, on a format akin to flipping 35mm film on its side, in Federation Square’s Deakin Edge. We spoke to one of the filmmakers involved in the project, Joost Rekveld, ahead of the screenings on Friday the 14th of August.

First I want to ask about form, because you started out shooting on film in 1991, on 16mm, then jumped to 35mm in 1999 and have only shot a film on digital once – in 2009 for Beat Time.

No, that’s not really true – it’s more complex. Actually my background before I started filmmaking was electronic music, and the first film that I made is one for which I wrote software, so a computer system would generate it, pixel structure.

What year was that?

That was, I think, 1990. At the time, computers didn’t have video output, it was very very difficult. I had this piece sitting in this Atari computer that I had, and which I could never really show, because I couldn’t really render it. Partly due to lack of experience and partly because I wanted to get more into moving images, I actually decided to work on film, to study it more and be able to screen it and, I was also at the time very interested in experimental cinema, and to show things in those circuits. So then I started to work on Super-8, and then 16mm. So that was my first experience with computers, before I started using Super-8. Also when I made films, basically after 1995-1996, I started making my own mechanical optical devices to make images, and from that time I also started using computers to control these machines, so that I could actually really compose these movements and make animations, a sort-of automated set-up. I know there are a lot of filmmakers and image-makers who at some point sort of embraced the digital or stayed away from it, and for me this has never really been an issue, for me these were always interwoven, and it’s part of a continuum of tools. Anyway, what I find really important in my work is also that I make my own tools and develop my own tools to be able to develop my own visual language.

Is that how you essentially print your computer language to celluloid? With your own tools?

Yeah, and there have been also many different ways; in this first piece that I was talking about, at some point when I got the skills to work on 16mm I animated and transferred it to film myself, and then later, when I started working on 35mm, then there was a piece I made in 2009, which was the first piece where I got it really transferred. I wrote my own software and then it was mostly printed to celluloid, which is similar to what we did for Vertical Cinema.

I did see that all ten films in the Vertical Cinema program were digitally created or manipulated and then transferred to celluloid.

The screening format is 35mm, flipped on its side. There are now two projects, modified in which the mechanical part is flipped 90 degrees. It’s only screening on film as well, no digital.

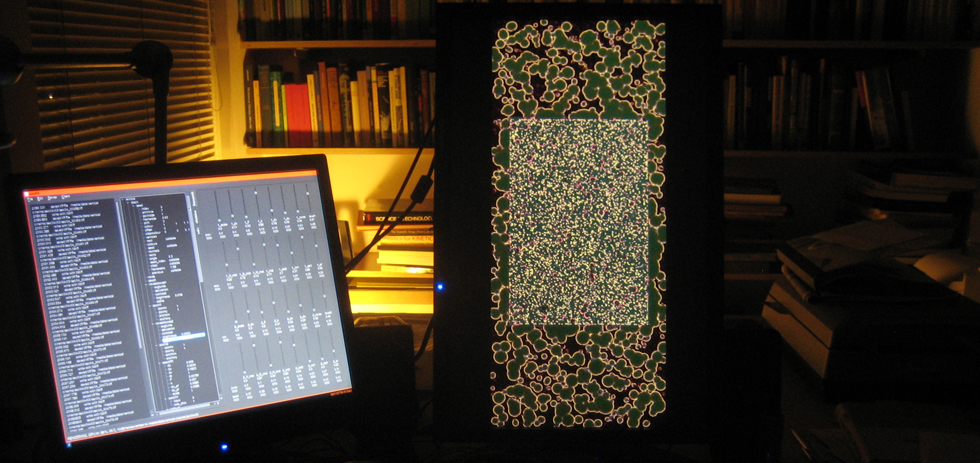

It seems like a really interesting clash of visual cultures, because you have an unusual projection method, using electronically developed art – all different, of course, but still computers are involved somewhere, as in those great computer screenshots on the Vertical Cinema website – but it’s still being shown on an old format of film.

Yeah, I think that this sort of ambivalence is deliberate. On the one hand, film is disappearing, and you could say that this project is a twisted homage to classical cinema, but it’s also another way to show that, even with celluloid, not all possibilities have been exhausted yet. This disappearance of celluloid is something you see more widely in experimental cinema, basically what remains is the crafty part, the handmade part, and so film is going through something of a revival in a lot of different places, people who hand-process the things. At some point, this will be the only way to use film, when you can do it all yourself, because all of the labs are disappearing.

I think there’s also an interesting clash in the Vertical Cinema project in terms of space. It has been screened often in churches, which isn’t really a cinematic space, despite the projection. It makes the project feel more like a gallery installation, in my mind.

Yeah, I think that this is something that is also an aspect of the subculture, or the context for the project, is that there’ll all artists who worked in cinema, have worked in electronic music or live performance and visuals, and an art context. So it’s really just this area which can be also in all of these places, and it has been shown in a couple of museums and film festivals and even music festivals now. In a sense also I think that it’s interesting, being at the festival here, which is really just cinema.

At which festival did the project start?

That’s the interesting thing, it started at a festival in Krems called Kontraste, mostly a music and sound art festival, and their main venue there is a very beautiful old church, and I think the first time I heard about this project is when Sonic Acts went to have a look at the venues, because they were asked to curate a series of festivals there. When they saw the church they thought that it would really be difficult to screen, “it’s so narrow and so high” and then they said “well we should just flip it on its side”. And that started out as a kind of joke, almost, and then three ears later you have the premiere of Vertical Cinema in that space.

That seems similar to an approach you take in your own artworks, this restriction being placed upon you. You’ve said in interviews that you apply a ‘principle’ to your works – whether speed of film, light. Did you find that as a result of this the Vertical Cinema project fit into your body of work more easily?

Yeah, in a sense it sort of fit in; I had made other pieces on 35mm before. I know for artists in this piece, some of them, the challenge in this commission was to make something on such a big format. But I had been working on Cinemascope before so it was nothing new. What is of course new is this monumental aspect of it. The piece I made, #43, I really started to use the actual frame of the screen as a generating principle. So basically the system I set up is a system of pixels. You can look at basically all of the pixels on the screen communicate. Then an event sets them off, I start with a white flash on a part of the screen and then at some point that becomes the whole frame of the film.

I’ve read that you’re not only interested in science and technology in developing your films but also philosophy. You were also a film professor?

I’ve quit now but I had been teaching for eighteen years almost and I was also a head of department for six years. And a year ago I decided again to focus on my own work.

Well, yeah, it seems from what I have read you find it very important to align art with philosophy.

Yeah, in a sense. It’s important for me, it’s how I get my ideas, it’s how I work. I do find that in the end, at least or the kind of work I make, that I don’t think it’s necessary to first read a whole philosophical description. I think it’s also really important, and it’s also where my connection to science comes in, I’m really inspired by a lot of scientific theories and I also like to go into the history of science and find sort of dead ends which have not been explored further, which still have the potential for generating images or just strange and interesting ideas. If you look at #43, I started from a mathematical model of how nerve pulses travel through tissue, which is all very abstract and mathematical but if you look at the images these model can produce, then you recognise lots of things, you see a lot of similarities between those kind of propagation and how, for instance, colonies grow and mosses grow, these kind of things. And for me that’s really the appeal of these kinds of theories, that once you start visualising these things you see actually how it resonates with things much closer to us and which actually are close to processes we see around us or process we know from our own bodies and that I find a very interesting like, which is very much unexplored, like the science now is all about theories and the mathematical articulation of things but a lot of these theories, this model is also related to these models for growth and I find it interesting to show those kind of analogies and also make it possible to connect to these ideas in a way which is completely non-verbal, where also you don’t need a Masters in Philosophy to understand it.

When you were teaching was it more theory or production?

In Holland, it was an art academy so I was teaching artists, and in the end it was all about production, and all the theory we were teaching was geared towards letting them formulate their own theoretical context. Mostly what I was teaching was experimental film and, at some point, it went much more towards this intersection of art and science, sort of biology-inspired art.

There’s this notion that experimental cinema is often at a distance from audiences – I don’t think it’s as much about understanding, as you said people have a reaction to light and sound regardless of knowledge – it’s that there’s a lack of access. Vertical Cinema is an interesting project because it’s bringing visual video art to a film festival like this. Do you find that general distance difficult in terms of getting your work out there?

No, I’ve had experiences like this, and of course experimental cinema is very wide. I think this really abstract animation work and abstract cinema is easier because there’s no language, and very often it’s less theoretical, and I think also there is a whole culture of experimental pop music with visuals and its very close to that. So I found that, though music festivals, that it’s actually quite easy to show these works to a much larger audience. I’ve shown like quite a lot of programs on the history of abstract animation at these kind of festivals; perhaps you repackage it and call it ‘Psychedelic Cinema’ or whatever but, in a way, it’s very easy to show these works. So I think also for Vertical Cinema, the reactions we’ve had from different festivals have been very positive.

Are there any specific festivals where you’ve shown your work that you think really do encourage experimental cinema? I know you’ve had quite a lot of your work play at Rotterdam.

Yeah, I think Rotterdam is a special case because it’s part of both of the sort of large international film festivals in Europe and also they have always had, especially in the last ten years, also shown experimental film. In a way, Rotterdam is so big that the experimental section is the biggest experimental film festival in and of itself and it’s almost a festival within a festival – which is both good and bad, I guess. They’re a very important platform, I think, for experimental filmmakers in Europe but what I find most interesting is festivals who really look for new audiences and I find that there’s something in festivals, especially in Eastern Europe, who manage to activate a whole new audience. There’s a festival in Zagreb called 25 FPS which I thin has amazing program, which really intercuts all this cinema, music, video, media arts and experimental film and also have huge audiences.

That does make sense, because video art and experimental cinema are at that weird cross section; as you said so many experimental films are dependent upon sound, which traditional film is but not to the same extent, it’s art, music, video together, a near uncategorisable thing, so it’s great to see some festivals find a place for it. You’ve said that #43 is your second ever commissioned work.

Yeah, that might be true, depends on how you count them.

What differences do you see between making work for yourself and those commissioned?

Well these kind of commissions are very open, in a way, they define a format and a length and a budget and within that you operate, and it’s not like there’s a very specific theme. In that sense, for me it’s still really part of my personal work. I have also worked as part of theatre productions, where I’ve done projection designs or light installations. There it’s much more like you’re part of a larger whole, there are more constraints. For me, personally, within these constraints I often feel free to try out things which I would normally not try out, so I don’t feel these constraints as like a prison, within that I’m always very happy to try out things. For instance, in these theatre productions I worked with a dance company for quite a while and within their productions I started to do, basically, sort of live visuals. Choreographers really work on the floor, so then if they have, sort of rehearsed a certain sequence, then you have to do back to the hotel and reprogram it and render and then you come in the next morning and the one thing you’re sure of changes, the sequence needs to be changes, slowed down or sped up three times, things like that. So then I figured that in order to be part of that process you need to have something where you can also work in real time, which was very interesting to develop.

What made you name almost every one of your projects, including the films, with these numbers?

I don’t know. When I started making films I knew a couple of filmmakers who did that, Oskar Fischinger, who is one of my heroes, he made like a series of studies; there was a filmmaker called Kurt Kren who numbered all of his films. Because these films are abstract, in some cases I find it interesting to give them titles to guide the associations and other times I find it completely redundant, or it imposes a frame which I wouldn’t like to have. The practical way to keep them apart is to use numbers.

Thanks for taking the time to talk to us.

It was a pleasure.