Inside Out has a lot going for it – a genuine and moving narrative, beautiful animation and design, and a third act emotional gut punch that will leave the hardest of hardened heart sobbing quietly in the corner. It’s also a real step forward for Pixar in terms of female representation – the whole film takes place in a young girl’s head, and the main conflict involves two female coded emotions.1

Yet the opening short, Lava, is problematic at best. Telling the love story of two volcanoes through song (and the potentially devastating story of their tectonic reunion), Lava falls into the same trap that so many animated films do – it makes a brilliant, evocative male character from an anthropomorphised volcano, and it makes a female character from a volcano that looks like a pretty lady. Why the female volcano must look distinctly human and conventionally attractive, while her counterpart is definitely a volcano, hits at the heart of one of the biggest issues in current film animation – women existing as a separate, codified entity, with a limited, often sexualised design and relatively narrow narrative role.

Lino Di Salvo, the head animator of Frozen, really hit the nail on the head while putting his foot in his mouth in 2013:

“Historically speaking, animating female characters are really, really difficult, because they have to go through these range of emotions, but they’re very, very — you have to keep them pretty… So, having a film with two hero female characters was really tough.”

Just to be clear, I’m not saying Di Salvo offered a good reason for this – in no way is the fact that female characters have emotions the reason they’ve been sidelined and homogenised. Most of Pixar’s creative strategy over the past 25 years has involved asking, “What if [BLANK] had emotions?”2 The fact that Di Salvo believes this, however, indicates a longstanding attitude in the animation industry that female characters are difficult because they have to be pretty – an issue that is only exacerbated by the fact that animation seems to have one model of female beauty.

In search of further answers, I turned to Brenda Chapman, the first woman to direct a major studio-animated film (Prince of Egypt, 1998), the first female director on a Pixar project (Brave, 2012) and the first female recipient of the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (also for Brave). To my surprise, she was defensive of Di Salvo:

“For the position he was in as an animator, he was absolutely right. It’s incredibly difficult to keep a female character on model and appealing within the limited directives he was given. That wasn’t his choice, but the choice of the studio’s directive – coming from marketing and executives down through producers and directors on to the character designers – which then goes to the animators. Female characters are too limited in the notion that they always have to be stereotypically beautiful. If the designs and concepts of appeal were more diverse, it wouldn’t be an issue.”

So who dictates what is pretty? According to Chapman, these days it is usually marketing:

“Before The Lion King (which was a hugely surprising financial success), the films were creatively led and supported by marketing. Now marketing calls the shots… and their vision is limited to previous successes. They don’t look forward or try to break creative ground. They want to stay in the safety of what is known to work, which in the end is a very short-sighted approach.”

There is no denying that marketing also has interests beyond the film itself – in a market where a film like Cars can gross more in merchandise than the combined box office of every single Pixar release, the film is no longer the product. It is the world and the characters, the potential for soft toys and branded paper plates and storybook apps all rolled into one ninety-minute expo. But that doesn’t solve the question – why is animation living in a world where a male volcano is a volcano and a female volcano is an aesthetically pleasing, conventionally attractive lady volcano, and why exactly is it a problem?

To get fully into the issue the animation industry has, we have to address character design, and specifically silhouettes. Silhouettes are a tool and a litmus test for designers and animators alike – in short, a good character should be recognisable from a blacked out image (silhouette), as should their movements, intentions and emotions. The Simpsons family are a good example – from a silhouette, any person should be able to distinguish each character. You can also easily imagine the silhouette of Homer choking Bart, Homer leaning over Bart, Bart’s gaping mouth and lolling tongue, et cetera.

A good silhouette is iconic – characters like Maleficent, Shrek and even all of the Seven Dwarves are easily recognisable as shadows. However, the more recent female animated characters lack any real distinction in terms of their silhouettes – all have big heads, small waists, an hourglass figure and the same, exaggerated human look. Creative risks these are not. Even more distinctive female characters like Joy, Sadness and Disgust in Inside Out adhere to the ‘human’ rule – although director Pete Doctor states they were designed to look like a star, a teardrop and broccoli (respectively), all three could be sisters when contrasted with the two male leads, Anger and Fear. Anger is a squat, red, brick-shaped being, while Fear is lanky and vertical, designed with a raw nerve ending in mind. The contrast between the two male characters is clear, and allows for a full range of motion and animation, and while it is a step forward, the blackout silhouette lineup of Inside Out’s five emotions reveals two very distinct characters, and three humans.

There is, of course, more to character design than simply a silhouette – the placement of facial features and the associated shapes is incredibly important. As humans, we are drawn to faces, and animators in the CG sector have to carefully avoid the uncanny valley, hence the need for caricature, variable design and visual cues. Circles are friendly, and the basis of most heroes; they can then be paired with the stability of a rectangle or the speed of triangular points. Villains, for the most part, are a combination of stability and speed, without the reassuring circles. Female character design, unfortunately, seems to have stopped listening at “circles are friendly”. The female form and its face is made up overwhelmingly of circles, with big open eyes, the rounded hourglass figure, the circular head balanced on a disproportionate neck. Tiny points are added at the chin and (usually upturned, button) nose, but these add depth and shape, not character, and are almost universally agreed upon throughout the industry.

There is a relatively simple explanations for this gender binary in character design, offered by animator and designer Sarah Airriess. When asked whether she felt restricted in the range of female silhouettes, Airriess agreed – to a certain degree.

“Commercially, yes. I think it’s important to note, though, that this isn’t just the fault of a sexist animation industry: there are more specific visual cues to a design being ‘female’ than ‘male’ even when it’s got no apparent gender whatsoever. The figure in the Ikea manuals reads as male, for example, despite having no real facial features or ‘male’ signifiers; Muppets read as ‘male’ until designated otherwise with eyelashes and/or hair.”

This is true, in the same way a volcano is male unless proven otherwise with long hair and a slender neck. That being said, animated characters are rarely voiceless: the lady volcano of Lava speaks and sings in a clearly female voice, as do most female animated characters, and here’s where it gets really weird. There is a strange tendency for female characters voiced by men to require less female coding; characters like Ros in Monsters, Inc. and Edna Mode in The Incredibles defy explicit feminine coding in their design and their voicing. However, neither of these were ‘appealing’ characters; both were comic additions to the story, and therefore were not feminised. However, they were both incredibly powerful and influential characters within their worlds, while other female characters in their films had more stereotypical designs (Cecelia, Elastagirl and Mirage) but ultimately existed to assist male characters rather than complete their own arc. To quote Airriess:

“Perhaps there is a deeply ingrained cultural bias to default male-ness, but you get into some very grey areas between ‘inculcated culture’ and ‘cerebral hard-wiring’. That said, commercial animation tends to keep its female designs in an itty bitty tiny box within the objectively much wider box of potentially feminine design. The tiny box sells better.”

Another issue with female character silhouettes is the current trend of cutting corners – female characters are given distinctive hair colours and styles instead of distinctive silhouettes. It would be possible, for example, to tell Anna and Elsa from Frozen apart with the cue of hair colour or whether the silhouette has one braid or two, but on an uncoloured model (hair is added in later in surfacing) the two are virtually indistinguishable. The problem is that this is lazy design that is almost exclusively used on female characters. “The hourglass still prevails in female design, sadly,” says Chapman.

“There is a great example online, that I’m ashamed to say Merida and Elinor both fit into. An artist traced the general shapes of many of the Disney and Pixar male characters and found all sorts of shapes, rectangles, circles, triangles & trapezoids right side up and upside down. The females? All slight ovals and circles. No variation whatsoever. When you look at the faces the only differentiations are eye size and placement, hair length, color or style.”

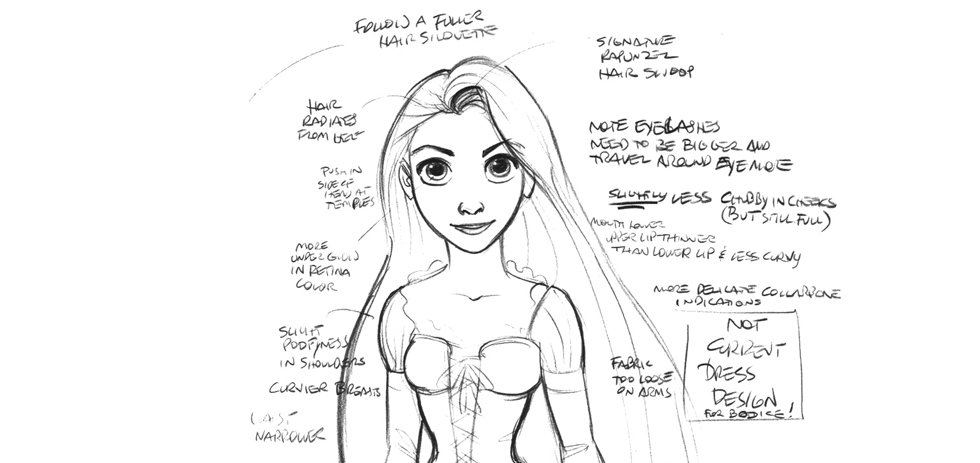

This is a criticism that could easily be levelled at the film industry at large, and absolutely should be, but the real issue with the lack of creativity in female designs is that it dehumanises women. In a world literally created from scratch, an entire gender are relegated to a single form. Design itself is a laborious process, particularly in the constantly advancing technologies of modern animation. It is virtually impossible to go back into an old film project and ‘borrow’ the assets of an existing character; they must be built. No single Shrek film used the same technology, each one called on new models to be built and rigged for animation, with better texturing, physics and motion. So each time a new female character is built, the animator is making both a conscious and unconscious decision to design a new model in almost the exact same way as hundreds of others before it. More worryingly, the female model is only becoming more restricted. Notes on Glen Keane’s Rapunzel concept sketches call for a bigger bust, smaller waist and wider hips, on a character who celebrates her eighteenth birthday in the film. But the age discrimination goes both ways, as Brenda Chapman found out on Brave when trying to create a more realistic middle-aged mother figure in Queen Elinor:

“It was frustrating – but in the end I felt we had a compromise that leaned in the men’s favour. I wanted to give her the middle age spread and more signs of age – they vetoed that. They felt she looked too “haggard” if I gave her any kind of age lines around her mouth or eyes or if I made her nose a little bigger… or tried to age her neck. So yes, she’s beautiful, but she’s still bigger in the hips than most female characters you’ll see… I am extremely grateful for the wonderfully strong and brilliant performance of Emma Thompson – to give Elinor that toughness of age and experience only a mother can have.”

Compromise in the men’s favour is arguably the heart of the issue – the animation industry is undeniably male dominated. There were more than 60 years between the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and Chapman’s debut as a director – 60 years without a single woman at the helm of a Hollywood animation. It wasn’t until 2011 that Jennifer Yuh Nelson became the first woman ever to solo direct an animated film with Kung Fu Panda 2 – a film that promptly made her the most successful female director in Hollywood history. And while Airriess is hopeful that we’re about to experience a boom in women in animation, judging by the number of women in art school, Chapman is less optimistic after more than 25 years in the industry:

“I felt we made big strides when I started at Disney on Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, in comparison to Snow White and Aurora.… I was the only woman on those story teams, and the men were right there with me, leading! They were trying to change the image of a princess as much as I was. But later, when the princess movie became passé, it became more difficult to convince the studios that female protagonists were just as valid a hero as a male. It was interesting on Brave – I got a lot of push back about the story in the beginning from the so-called “brains trust”, but luckily John Lasseter had nieces that he wanted to make a film for. But as time went on, being the only woman in the room once again, it was very difficult to make them understand a woman’s perspective on female characters.”

Airriess also offers another explanation for the gender binary in character design, as a result of the systemic male domination of the industry.

“When artists are starting out they tend to bias their designs towards their own gender, and have to learn the opposite one as they develop. Young male artists struggle a lot with drawing feminine-looking women (as opposed to boyish figures with cinched waists and boobs) which is, I think, why they tend to get stuck on the formulaic body and face shapes you see everywhere. If you learn to draw one woman you can just change details for every other female character you ever draw, which saves a lot of work! And there hasn’t been much demand to challenge this laziness because that formulaic design has always been all that is required. Some do learn, and do a great job of it, but a lot just stop at the one design. I, on the other hand, had to learn how to make characters look male, and took years to be able to draw an actual “manly” man. I can think of at least four other female artists off the top of my head who had the same problem. The difference is, we need to learn to cross the line because there is more variety expected in male characters.”

So while female artists are pressured to learn male designs, the male domination of the animation industry has meant not only that female characters are underdesigned, but that they are also underrepresented to the point where these design issues become hard to notice, due to the scarcity of female leads. It might seem almost too easy to target Disney in any discussion of female characters, particularly with the recent examples of Rapunzel, Anna, Elsa and Honey Lemon, who have practically identical features – but the reason Disney is such an easy target is because it is one of the few studios releasing female-led films. Brave was Pixar’s first female led project in more than one way – Merida was the studio’s first female lead, and it has taken three years for Inside Out to follow with another female-driven film. Both films, coincidentally, have their origin in the female relatives of male creatives – Chapman mentions John Lasseter’s nieces, while Inside Out was inspired by Pete Doctor’s daughter. But while this championing is good, and has led to increasing representation on-screen, it is not enough.

Dreamworks’ Home is either its second or fourth female vehicle (depending on whether you count The Croods and Monsters vs Aliens, which both featured prominent women in an ensemble), while Blue Sky Studios have one female led picture (Epic) and Sony Pictures Animation has had none. Disney, in their recent revival of the Walt Disney Animation Studio under John Lasseter, have released three female-led films since 2009 (five if you count Pixar films, and eight if you include the theatrically released Tinker Bell films from DisneyToon Studios). While they might provide the most obvious examples of flat female characterisation, Disney have also given us some of the most diverse female characters in recent years, like Gogo Tomago, Sergeant Calhoun, and Kanye West’s spirit animal, Vanellope von Scweetz.

However, there is no denying that female representation flourishes best in the hands of female artists, particularly as more women take leadership positions in the industry. When Jennifer Yuh Nelson took over the Kung Fu Panda franchise, Tigress went from an unattainable beauty to a nuanced and complicated character. Most of the technical development that defined Brave was done under Brenda Chapman – “The hair is what made us able to make the movie!”. And, as easy as it is to target Frozen as an example of unilateral female design, it remains the biggest animated film of all time, starring two sisters – and, if you like, you can always say that Jennifer Lee’s strength as a director was in the storytelling of the film, as her background was screenwriting.3

But this has hardly been a secret. On Ratatouille, Brad Bird made a point of having female animators working on Colette as much as possible, and the result was a visually distinctive and engaging character. And back on the first animated film ever, the women in the ink and paint department applied their own rouge to Snow White’s cheeks, giving her that distinctive glow. Women have always been more accurately represented by women, and it’s more than likely that the true reason for the stagnation of women in animated films is the stagnation of gender representation in the industry.

On television, though, is where you’ll find the most diverse and interesting female characters that animation has to offer. Rebecca Sugar’s Steven Universe has been widely praised for its complex explorations of gender identity – the eponymous Steven and his father Greg are the only recurring male characters, while the world is populated by powerful female characters and the mystical Crystal Gems. Sugar intentionally created the gender dynamic to “tear down and play with the semiotics of gender in cartoons for children”, and it’s no coincidence that Sugar is the first female show runner on a Cartoon Network program. Even from a pure design perspective, the three central Crystal Gems are interesting and uniquely designed, there is no chance of mistaking one silhouette for another. Sugar’s old stomping ground, Adventure Time, presents a world run almost entirely by a series of powerful (and increasingly specific) princesses, who may occasionally require rescuing, but more often than not are too busy ruling kingdoms, creating mad science experiments and doing the rescuing themselves. Nickelodeon’s The Legend of Korra wrapped up last year after four seasons of intense action and complex characterisation by sending its two (very distinct) female leads off into the sunset together.

As for the future of film animation, and whether it will follow television into more autonomous and female-driven productions, we can only be hopeful. Inside Out has already grossed more than $600 million in the domestic market, even going head to head with Jurassic World. Pixar’s Finding Dory is due in 2016, as is Walt Disney Animation’s Moana and Yuh Nelson’s Kung Fu Panda 3. And as for the increasing trend of women in animation, Brenda Chapman is cautiously optimistic. “I worry that it is a fad… which Hollywood is notorious for… but I hope that if we keep rocking the boat, the waters will calm and both women and men can run the ship.”

Disclosure: Tansy Gardam works for The Walt Disney Company, though not in the field of animation (although she did once stand very close to Pete Docter). Her views in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of her employer.