Auteurism may no longer be constrained to directors, and often film actors, writers and producers have been, in hindsight or upon release, considered the chief visions behind particular films. Even so, Ray Harryhausen, special effects titan, is a unique artist that deserves mention among those. This is both a testament to the vision of the films themselves (“Harryhausen films” is a more appropriate label than any sort of genre label, though sword-and-sandals pictures may be a good umbrella term) and a reflection of the reality of the film productions. He was never credited as director for his films, due to Guild requirements, but would often be given “story credit” or producer credits, with little doubt in the public imagination or professional environment as to whose films there were. Harryhausen’s landmark effects – a stop-motion process branded as “Dynamation” – revolutionised film effects, and provided fodder for the Saturday afternoon imaginations of millions, becoming staples on television after theatrical releases. New to Blu-ray in Australia, Via Vision Entertainment has packaged four of his most known films together with comprehensive extras. Containing likely his most famous film Jason and the Argonauts (which Tom Hanks famously called the greatest American film ever made) and the three Sinbad films he made for Columbia, this is a great introductory package for any one interest in old-school Hollywood magic, films of a particular artistry that makes them resonate as more than mere vessels for nostalgia.

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) 1 is a refreshingly simple tale, an action-adventure free from any subtext or irony, heroes are heroes and villains villains. Sinbad (Kerwin Matthews, the type of bright-eyed matinee actor who could only have achieved stardom in the 1950s) and his crew venture to the island of Colossa, where they are chased away by a giant Cyclops, one of Harryhausen’s most famous creations. In the process magician Sokurah (Torin Thatcher) loses his magic lantern, and forces the crew to return to the island by transforming Sinbad’s love Parisa (Kathryn Grant) to a minuscule size, which he will only undo if they retrieve the lantern. The basic plot is kept along by brisk pacing, handsome production design and one of Hitchcock regular Bernard Herrman’s best scores, though fully aware that it’s aces up its sleeves are the Dynamation sequences (such as the famous encounter with the two headed giant bird) or otherwise nifty effects, such as the set design of the interior of the magic lantern our Princess is captured within. It’s impressive, wholesome adventure filmmaking with a naiveté and unpretentious fun that’s hard to emulate nowadays, which is followed up five years later with Harryhausen’s most beloved film.

Jason and the Argonauts (1963) is somewhat more faithful to the original mythology than the Sinbad films are, 2 to an extent that it feels slightly oddly structured to a modern viewer in its approach to narrative arcs. Jason (Todd Armstrong) must avenge the evil deeds of King Pelias (Douglas Wilmer) who killed his family years ago, while protected by goddess Hera (Honor Blackman), who instructs him to find the mythical Golden Fleece. Just as Fellini Satyricon ends abruptly, mid-sentence, the final act of Argonauts provides a jolting left curve as the revenge plot that drives the motivations for the film is dropped as other antagonists emerge and the film ends before Pelias can be killed, but not before some of Harryhausen’s most legendary sequences are staged. The sword fight with the skeleton warriors is probably what the film is most known for, but the encounters with the giant bronze statue of Talos and Triton show an ingenuity and skill in filmmaking that make them remarkably effective. Although these films are helmed by journeymen directors, Don Chaffey (no doubt in consultation with Harryhausen) uses deceptively simple exercises in perspective and angles to seamlessly cut between Jason and his men, and the apparently gigantic figures to clearly establish spatial relationships and engaging scenes of terror and awe –the emergence of Triton for the sea is particularly arresting. The plot is fun, and occasionally cheeky – the legend is whitewashed for mainstream, all-ages consumption, but side-plots such as the homosexual relationship between Hercules (Nigel Green) and Hylas (John Cairney) isn’t just winked to, but actually touching for those familiar with the characters. Bernard Herrman returns again, polishing off a very pleasing production.

The latter two Sinbad films aren’t quite as accomplished, but no Harryhausen film isn’t worth watching. The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) is probably the weakest film in the set; Sinbad is played by John Phillip Law, better associated with European camp films of the era (Barbarella, Danger: Diabolik) and somewhat ill-equipped for the straight-faced charm of the legendary sailor. Likewise, romantic interest Caroline Munro doesn’t fit the mould, closer to a Bond girl than adventure film princess, and its hard not to object to the consistent fetishisation of her midriff and cleavage, accentuated by some outrageous costume design. In fact, perhaps the damning flaw of this film is that it is far more interesting in fixating on Munro’s “special effects” rather than Harryhausen’s. But it’s redeemed in parts, the climactic battle with a six-armed Kali is a showstopper, and it’s bolstered by a charismatic villain in future Doctor (and Little Britain narrator) Tom Baker.

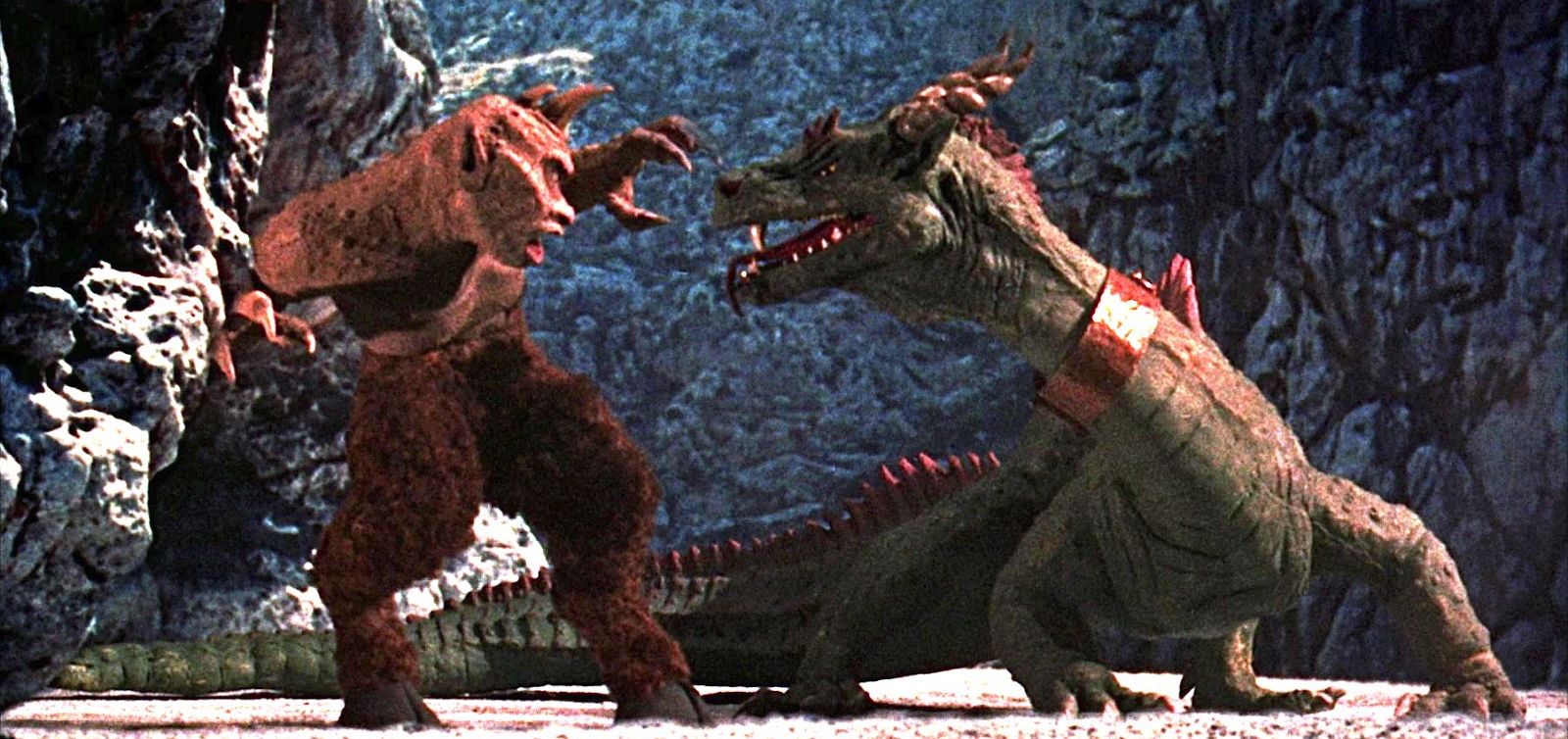

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) is likewise hampered by the conflicting tonal issues of the previous films, stuck between the Romantic adventure of the early Harryhausen films and the camp/sex appeal desired of the 1970s, an issue perhaps best personified by the casting of a bare-chested Patrick Wayne. It’s also a little long, despite having the most simple plot of all the films – the heir to a kingdom is turned into a monkey, and Sinbad needs to find the one wizard who can undo the course to stop the evil step-mother Zenobia (Margaret Whiting) seizing power for herself. In spite of this, it ends as a lot of fun, with some of Harryhausen’s best work on offer. The robotic slave Minotaur who chases the crew with Zenobia is great, and a number of other creations manage to show moments of genuine emotion and vulnerability at points, particular the giant caveman. There’s an awkwardness to this film that’s kind of fun, between Harryhausen’s artistry and the campier aspects of the human drama, and perhaps the most fun and telling part of this film is seeing John Wayne’s son out-acted by a stop-motion baboon.

The films come to Blu-ray in impressive transfers, generally adhering to the rule of thumb that the newer films generally look the best, and some scenes of special effects wizardry look particularly grainy due to being made of different source elements. Detail on human skin tones and costumes is all pleasing, although thankfully the Dynamation creations aren’t exposed by the increased sharpness of HD. The scores of each film are faithfully reproduced, and there’s an absolute trove of special features between the discs. Features on the Dynamation process (one charming one with Harryhausen devotee John Landis) abound, as do some informative audio commentaries, even if the ones with Harryhausen verge on the idolatry from the other contributors. All indications suggest this collection is from the same versions of these films available in other regions that have been available for a while, but to have them on disc locally and in one package is great to see – there won’t be too many better releases to hit Australian shelves this year. Anyone with a passing interest in classic Hollywood adventure films or the history of film practical effects shouldn’t hesitate