The Big Nowhere (to be seen) is a short-run feature that will run for eight separate installments, all penned by Melbourne-based writer Andrew Nette. The aim of this column is to focus on the best noirs that most people have never heard of and what they tell us about what film noir is, looking at plot, production and reception.

Anyone lamenting the current trend of lengthy mainstream cinema releases should check out Hubert Cornfield’s obscure 1957 film noir, Plunder Road. Clocking in at just 72 minutes, this cheaply made little heist story achieves an atmosphere of suspense and level of thrills not seen in many films twice its length.

The Film

Plunder Road opens on a bleak rain swept night. A group of masked men in three trucks head to rendezvous with a train transporting ten million dollars in gold bullion. They plan is to heist the gold at a deserted stretch of track outside Salt Lake City, split it amongst the three trucks and drive to Los Angeles.

The job goes off without a hitch and as the robbers drive away they start to congratulate themselves. Eddie (Gene Raymond), the college-educated mastermind of the operation, cuts them off: “Before we start congratulating ourselves, let’s remember, we still got 900 miles to go. Nine hundred miles through every cop between here and the coast, and you laugh like a couple o’ clowns.”

The robbery unleashes a huge police search, detailed, in typical film noir style, through snatches of news on the truck cabin radios. It will not spoil your enjoyment of the film to say the cops apprehend the men, either dead or alive, one by one, until the only ones left are Eddie and his driver, Frankie (Steven Ritch). They make it to Los Angeles were they meet up with Eddie’s girlfriend, Fran (Jeanne Cooper), in a rented garage. Eddie has an ingenious idea how to disguise the gold and get out of country to Mexico. They just have to get across the border to be in the clear.

Plunder Road may be a straight down the line ‘poverty row’ film noir, but it does its job well and Cornfield uses the sparse, cheap feel to great affect. The film has no dialogue for the first 13 minutes and the script that follows moves briskly and to the point. The film excels at rapid-fire thumbnail personality sketches of the heist crew. In addition to Eddie, there’s Frankie, a former racing car driver now banned from the sport due to various unspecified rule infringements; Skeets (Elisha Cook Jr), a recently released from prison career criminal who plans to use the money to take him and his son to Rio de Janiero; ‘Commando’ Munson (Wayne Morris), a former stuntman; Roly (Stafford Repp), a nervous, gum chewing thug; and Fran, Eddie’s resourceful secretary girlfriend. There’s also a sprinkling of wonderful bit part characters including the elderly gas jockey, whose death at the hands of Munson, leads to one of the trucks being intercepted by police, and a waitress in a small town diner who, in reference to the robbers and unaware who she is talking to, tells Eddie and Frankie: “You know, I’d like to see them get away with it.’

Turkish born Cornfield directed only a handful of movies, including another B noir, Sudden Danger (1955) and the strange 1968 British/French co-production, The Night of the Following Day, starring Marlon Brando, about a kidnapping gone wrong, on which the director and star apparently had a highly dysfunctional relationship.

Of the cast, Repp may be familiar to some as Chief O’Hara in the ’60s incarnation of Batman. Cooper had a long career that stretched from 1953 until her death in 2013, when she was still working as a fixture in daytime soap The Young and the Restless. Morris got his big break alongside Edward G. Robinson and Bette Davis in the 1937 film, Kid Galahad, before joining the navy and going to fight in the Pacific. He career never recovered from the gap of four years at war and he spent the ’50s in small budget films like Plunder Road.

The most recognisable face is Cook. A noted character actor, with his bug eyes, small statue and permanent look of aggrieved disbelief, he played losers and cheaters in a raft of films, including numerous films noirs (Phantom Lady (1944), Born To Kill (1947) and The Killing (1956) to name a few) and later in his career cult films such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Electra Glide in Blue (1973), and then onto various television roles until the late 1980s. Little is known about Cook who apparently spent his last few years of his career living at the fringe of Californian desert, away from Hollywood, without an agent. He is in top form in Plunder Road as Skeet, a habitual criminal and motor mouth, nervously sharing a cabin with the brooding Munson.

The Trope

One could include Plunder Road amongst the small but influential number of trucking film noirs, including Jules Dassin’s Thieves Highway (1949) and Raoul Walsh’s tough early noir They Drive By Night (1940), with Humphrey Bogart, George Raft and Anne Sheridan. Parts of the film share elements with Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 classic, Wages of Fear, in which a group of down on their luck men are hired by an unscrupulous oil company to drive an urgent shipload of nitro-glycerine across a stretch of mountainous South American countryside. Given Cornfield’s cosmopolitan background included growing up in Paris, where he immersed himself in French film and was reportedly friendly with people such as Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Traffaut and Jean-Pierre Melville, there may be much more to the comparison than appears at first glance.

But first and foremost, Plunder Road is a heist film, of which there are many examples in film noir. Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Kansas City Confidential (1952), and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956), are just some of the titles that spring to mind. Unlike most of these, the action in Plunder Road starts right from the get go and there is no set up or orientation for the viewer.

What it has in common with every other heist film noir is that the heist always goes wrong. As begets America in the ’50s—a culture in the throes of Cold War paranoia, the lingering after effects of the anti-Communist HUAC trials and moral panic about crime and juvenile delinquency still felt—criminals were never allowed to get away with their misdeeds. But it is the manner in which the heist film thwarted criminal desires that is so engaging. Technological problems, human behaviour, accident and bad luck all play a part in the trope of a film noir heist going wrong and all are present in Plunder Road. And, the more complex the heist and desperate the gang of men and women involved in it, the more likely it is that something simple will go awry.

The beauty of the heist film, and what works so well in Plunder Road, is that apart from being an excellent vehicle for moving the plot forward and creating a sense of hard boiled tension, the context and atmosphere in which the heist takes place and inevitable problems that arise after it’s been pulled off are just as important as the actual act of robbery. The men and women who pulled the heists were the some of film noir’s best foot soldiers. They realise the odds of life are stacked in favour of the rich and powerful and decide to take a slice of the American Dream for themselves, even though they know few of them will come out alive.

After being completely unavailable and, therefore hard to see, for many years Olive Films recently released Plunder Road.

Andrew Nette is a Melbourne-based writer and reviewer, whose work on film has been published widely. He is co-editor of Beat Girls, Love Tribes and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 – 1980, forthcoming in early 2016. His online home is www.pulpcurry.com. You can find him on Twitter at @pulpcurry

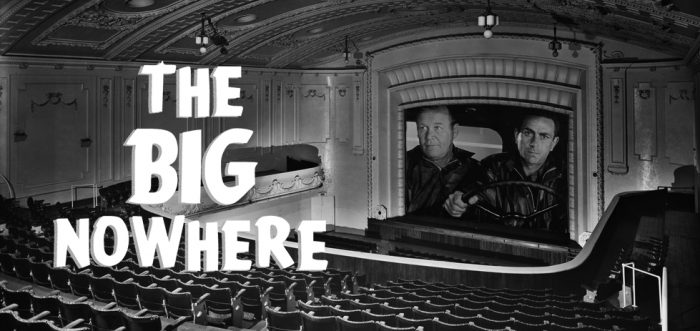

The header image for this series modifies a photo from the Harold Paynting Collection at State Library of Victoria and is used by 4:3 under a CC BY 2.0 license.