It is strange that we should get three features on the life and times of American chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer1 – the most recent being this year’s Pawn Sacrifice, apparently a kind of paranoia-inflected Cold War yin to Bridge of Spies’ Spielbergian yang that has Tobey Maguire starring as Fischer and Blood Diamond director Edward Zwick helming – while the prodigal Polgár sisters of Hungary have only briefly appeared in a jokey TV special called Chess Kids, without so much as an interview. Then again, as the long overdue feature documentary The Polgár Variant charts Zsuzsa, Zsófia and Judit’s personal and professional journeys, it also posits their chafing against the judgemental, over-masculine attitudes of both the Hungarian Communist regime and an international chess circuit as a case of women denied the same rights as their male contemporaries. Director Yossi Aviram stridently pursues both their impoverished upbringing and their success in the male-dominated world of competitive chess, creating a engaging, tidy feature that falters in his weak attempts at self-insertion.

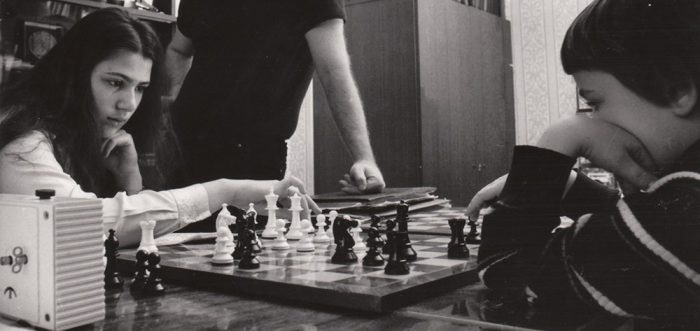

Aviram goes with a formally conservative approach, as with so many documentaries about subjects breaking long-held conventions, and hence he jumps from a montage-heavy opening primer down to a street-level walk and talk. We encounter Judit in rain-slicked streets with her young child in tow, as she takes us around the shopfronts and alleyways she and her sisters once called home. After Zsófia amusingly gets permission from the new tenant to take the camera crew through her old home, we are shown the cramped confides where the girls carries out their intense, hours-long training routines. These are intended to ground us in the same spaces where they mastered the stratagems fuelling their rise to fame and fortune later, but sweet as it is, the reminiscing feels like wheel-spinning next to stretches of career recounting that are only a tad more lively.

As for the Polgár sisters themselves, a fair amount of screen time surpasses before we get proper introspection from them beyond blink-and-you’ll-miss-it talking heads and an impressive array of footage from their television appearances. They are all remarkably well-adjusted for people who have had intense competitive pressure applied to them from as far back as age four, with no resentment and nothing but fondness for the sport they rigorously applied themselves to. The one possible source of personal friction in the family, László’s hyper-specialised parenting strategy, is something one would charitably call unorthodox, but if there is even a hint of abuse in László’s methods, it is nowhere to be seen. If anything, it’s heartily endorsed as his way of coping and progressing from the tragedy inflicted on his extended family by the Nazis, and a way of improving the lives of those kin he has left. Its biggest critic is Zsófia’s husband, who calls it a gamble he does not want to practise with his own children, but he swiftly stresses that it paid off in the case of his wife and sisters-in-law.

Despite this disciplinary intensity being the titular variant, Aviram is in no hurry to examine its implications for similar home-schooling-cum-competitive-training methods. It was what it was, the Hungarian People’s Republic acted as a speed bump to it on numerous occasions, and Aviram lets the experiences speak for themselves without steering the conversation in any especially barbed fashion. Adding to the film’s slightness is a wholly unnecessary narration, performed by Aviram himself, which tells us nothing that interview grabs and archival material alone couldn’t have done perfectly well. He starts to become aware of his ancillary role himself, since a late stab at investigative intrigue, where he goes looking for the physical database of chess games used by László to train his children, ends as perfunctorily as you’d expect of someone grasping for a “dramatic” ending. If there’s any kind of reveal, it’s that of the women’s current lives, in countries and new families far flung from the unit blocks of Budapest. It’s saved as a kind of ironic end note to their time as young feminist icons in a largely masculine sport, which won Judit enough fame even to be contacted by Yoko Ono, but which feels hollow next to the loving new families they have wilfully started, history-books making be damned.

It does feel like more of an anticlimax than Aviram might have been hoping for, as his finger-wagging narration and probing questions from off-screen indicate. The Polgárs’ story is one remarkably drama-free, however: László’s teaching strategy seems stringent but pays off, the sisters compete in international tournaments and then win as expected by their adult contemporaries, and they unhesitatingly decide to compromise their glory runs so they can tend to their husbands and children properly. These wholly understandable decisions in such unique circumstances are a more compelling story than the slick Behind the Music packages that would be afforded to their fellow male grandmasters. If only Aviram had embraced that from the start, he might have made The Polgár Variant something greater.