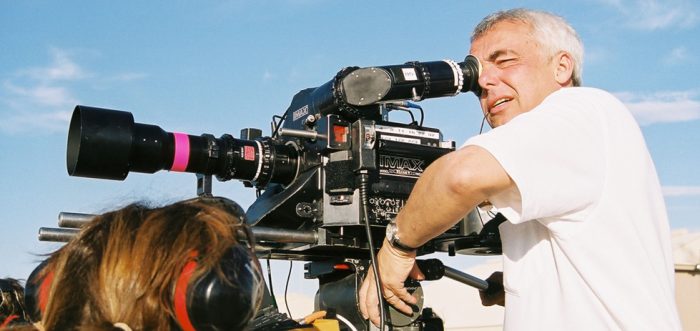

Stephen Low is one of the foremost filmmakers in the realm of large-format cinema. He’s been working on IMAX films since the 1980s, following in the footsteps of his father, director Colin Low. Both men made documentaries for the National Film Board of Canada prior to making the leap to IMAX and both have had a massive impact on the development of the form.

Stephen’s latest feature film, Rocky Mountain Express, opened last week at the IMAX in Darling Harbour, Sydney, five years after its initial release in the United States. We spoke to Low about his filmography, approach to working with a massive scope and the move towards digital capture in IMAX filmmaking.

I got a chance to see Rocky Mountain Express last week and I hadn’t seen an IMAX documentary since I was a kid, probably. So it was something of an eye-opening experience.

There are hardly any pure IMAX films being made anymore because of the cost of them, they’re so expensive to make.

Do you think that because of the fact that there are so few, the ones that are being made need to have some kind of educational value or be made for family audiences?

Well the science museums are the ones that run the documentaries not so with the cineplex or commercial theatres. The science theatres do have a mandate to run educational films.

Oh, right. I forgot that in the States IMAX is completely different to here. Here it’s just big standalone cinemas.

Oh, really? It’s a very unusual part of the market because almost all the theatres that are playing Rocky are big science museums.

For us here in Sydney I guess we’re a second or third-run IMAX theatre, we’re getting Rocky Mountain Express almost five years after its first release.

Four or five years, yeah. That’s not unusual because often theatres select not on the basis of newness but on the appropriateness for the theatre so these films go on for years and years. I mean, we’re still opening films that are 20 years old.

How often are you commissioned to make films by, say, tourism boards or by companies?

Not often anymore. Since ’08 things have been much more difficult to fund. We have three films that we’re working on right now but only one of them has a major sponsor. There just isn’t as much educational money out there as there used to be. IMAX is very expensive, a roll of film costs $6000 (USD). That’s the reason why there aren’t so many. We’re probably making, right now, the last of the pure giant-screen IMAX films using actual film, using 15/70.1 That’s what gives it its beautiful quality, this huge negative. No one is doing that anymore, film is too expensive.

That’s really disappointing. It seemed almost like this was maybe the one last hope for celluloid, IMAX film.

There are a few guys in Hollywood who trying to use it but it’s harder to fix than to use it because it’s so much dependent on light, beautiful light and dramas can’t afford to have 100 people sitting around waiting for the sunlight to come out. So it’s much more difficult. It’s very difficult in 35mm but you can light around it. A lot of films are shot with long lenses and so you can get close to the subject and light it. In IMAX with 120-degree angle lenses the light has to be a long ways away and so it’s very, very expensive. The night scene in Rocky was a couple of hundred-thousand dollars just to light it.

Wow.

Yeah, huge lights. Hollywood doesn’t even use those kinds of lights anymore.

In terms of recouping costs for a film as expensive as an IMAX documentary, perhaps one upside of large-format films is that there’s no real attack from the home video or streaming market. They’re an event experience in a traditional way. No one is going to try and get a rip of Rocky Mountain Express on their laptop.

We have resisted putting it out on video for that reason because it does get ripped off and put on YouTube and so we’ve tried to protect it but now we’re gonna release it because we need the revenue. The film has not made its money back and very few IMAX films really recoup. It’s not a business or anything to do with education. We pay back maybe a third of the cost of a film so we have to have sponsorship.

That big need to make back costs in home video does explain all the “IMAX 3D Blu-Ray” discs you see in video stores nowadays. I wanted to ask how you feel about the distribution of your films, specifically Titanica, which was recut for its DVD release quite drastically.

IMAX sold it to a studio [Miramax] and they re-cut it which, I shouldn’t have allowed it but I really didn’t have a choice. It was terrible, horrible actually.

I saw it on Netflix and started watching it and there was something off about it. It seemed so much like a traditional documentary – it had Leonard Nimoy doing voiceover, all of these talking head interviews. I stopped it after ten minutes to look up what it was like in IMAX and read about what happened.

It was really disgusting, actually but, you know, filmmakers are vulnerable in all forms. Directors get their films re-cut. There wasn’t much I could do about it. I probably should have done something but it’s too late now. Most of my films are intact, though. It’s just that one that was badly remade by a studio. You can’t win ’em all.

Do you hold out hope for retrospective screenings of your work?

Oh, we’ve had a few. Titanica was played in Detroit last year or the year before and I went to that, that was a lot of fun; a lot of fanatics and Titanic people had come to that. You know, these films have had good runs so it’s not like the normal sort of documentary world where you get only a few dozen people looking at them. Millions of people see these films, millions of people have seen Rocky Mountain Express and so that’s very satisfying. I think going forward there’s good news in the sense that projection will get a lot cheaper in the future because of the new digital systems, the Laser system that IMAX has pioneered, which in fact was better than film in playback because it’s steadier and sharper and a little more contrast, brighter. So the wonderful thing is that what used to be $40,000 prints are gonna be $2000.

Projection is kind of going out in front of capture. Capture has diminished in IMAX because film is so powerful and a negative is so big but projection is getting better so there’s going to be a future for anything shot with a big negative. That’s kind of a nice turn. It’s easier to project something than it is to film something, for some reason. So that part of it is good. You know, science museums don’t have a lot of money and although these projectors are expensive the running costs are a lot lower. Our prints for Rocky, that’s like a $30,000 print. Sometimes they get damaged and so the theatre has to pay for that. Anyway, I think there’s good things coming. The internet has changed the world for everybody.

What made you first take the leap from making documentaries for the National Film Board of Canada to doing IMAX shorts at Japanese expos in the ’80s?

My first Film Board film was for a producer by the name of Roman Kroiter. He was still working at the Film Board but he was a partner in IMAX, one of the founding fathers of IMAX. So the first film I made (Challenger, 1980) was kind of revolutionary, a film about building an executive jet; a business romance, if you will. And it was a huge hit, it went all over the world and it won many awards. So Roman asked me to do a film for Suntory, the Japanese World’s Fair in ’84 or ’85 and that was successful as well so that sort of kickstarted my career. I’ve been very lucky. I’ve made many IMAX films and I’m lucky to still be working at it. A lot of my contemporaries at the Film Board, their careers fizzled out because funding for documentaries is always tough. IMAX was a wonderful thing for me and it’s the ultimate canvas.

You got in reasonably early too. The first IMAX film, Tiger Child, was in 1970 and your first IMAX film was Skyward in 1985.

Yeah, I worked on Tiger Child and I worked on a space shuttle film with Graeme Ferguson (Hail Columbia!, 1982), another founder. After I finished my Film Board film there was interest in having me do IMAX, even early on. So I worked on Hail Columbia! and learned a lot from watching Graeme work. Then my father (Colin Low) did an IMAX film shortly after that. He did the first ever 3D IMAX film (Transitions, 1985) and I learned a lot on that and then I did the second one (The Last Buffalo, 1990). I did a lot of 3D but I’ve kind of reverted back to 2D because, for me, the 3D undermines the scale, the beautiful bigness of things, like the mountains. So I’ve kind of become a 2D enthusiast. 3D is very complicated to do well and it’s projected badly a lot of the time.

2D also puts a lot more focus on framing. In Rocky Mountain Express there is a lot of really nice, neat framing. The front of the train and the perspective from the front of the train, for instance. Are you at all familiar with the Norwegian Slow Television phenomenon?

It sounds familiar. What is it?

It’s this sensation on television over there where they film seemingly banal things in one take for a very long amount of time. It started in 2009 when their public broadcaster, NKB, bolted a camera to the front of a train going cross-country and broadcast all seven hours of it.

Yeah, I saw that.

When I was watching Rocky Mountain Express that came to mind. That awareness of time and movement.

Well a lot of people have come up to me and said “thanks for leaving the shots long enough”. Modern cinema is all about hyper-cutting and even IMAX – Hollywood guys who do IMAX, they cut too fast and it’s annoying. You have to like the old sort-of Lawrence of Arabia style where the shots are allowed to live and breathe and evolve. You can’t always do that but if you’ve got a good helicopter crew and you time things well enough there’s some shots in there where it evolves as you’re going. The train appears inside the shot and you follow it and let it evolve. We did that quite a few times.

A lot of your films seem to either be about letting the viewer experience something in the now – Fighter Pilot, The Ultimate Wave, Rescue 3D – or an act of restrospectivity, where you educate the audience on the history of a practice. Rocky Mountain Express seems to do both.

Yeah, I like that style. We first used that, well, it’s kind of a Canadian style, my Dad made a film in the ’50s called City of Gold which was a very famous film in documentary circles for both the Gold Rush and the Yukon. That film used a mix of beautiful 8×10 stills intercut with sort of live-action trips through the Yukon. That’s what Ken Burns used as a reference when he started and I think it’s a marvelous kind of style. I find the real people looking back at you are so wonderful, their faces – in this film the Chinese guys who built the railway, you know, individuals. And on the giant screen with a big negative it’s just wonderful. You’re almost reaching back to them. To me, the steam engine was the perfect guide. Its whistle, its presence. It’s able to bring spirits out of the woods.

Before we made the film, we never had proper funding for the film, so it was a huge leap of faith for us to make it anyway. I was in that place where the pillars are, the valley of the Illecillewaet, with my wife and we heard the whistle of the locomotive coming up and we were tracking the steam engine. It was so evocative that it was almost like it was calling back the spirits of the builders, the guys who built the railway and really saved the country. It just seemed so evocative to me that I had to do it, whether we were funded properly or not. The more I got into that film the more incredible it seemed. Some stories kind of fall apart the more you know about them but this one – the more I knew from flying in a helicopter and being up high and seeing the scale of the work it just seemed more and more unbelievable to me and remains so, that these guys built that with their bare hands and those little tiny woodfired steam engines climbed those mountains in the 1880s – it seems incredible to me.

You’re telling these big stories (construction of the railroad, saving Canada) but you’re telling through quite an intimate lens (shots inside the train, the stories of the men involved). It’s really sobering actually, to see the faces of the Chinese and Japanese workers who died building this Canadian railroad alongside a look at the scope of mechanical success. You’re film isn’t just a celebration, it makes people consider its history in a literally big way.

Yeah, it’s kind of a celebration of young men, these young guys that built the railroad and the courage that was necessary to build those trestles and the dynamiting and all of that stuff. It’s hard for men to be heroes anymore. The film has done extremely well in military museums, in Pensacola, Florida. It’s because young people, not just men, love the idea – they’re there volunteering for service to make a sacrifice, to be somebody important. That story of their young colleagues 100 years ago resonates with them. I think everybody wants a chance to be a hero in some respect and it’s harder and harder in this world.

What has your experience shooting The Red Rocket (short, 2014) on digital been like?

It was a lot easier to shoot digital and in many ways a lot more fun; you can leave the camera rolling, you can mount four cameras on a streetcar or something. I’m really enjoying it. I’m doing a film on international navies of the world, we were filming on an aircraft carrier last week. It’s really fun to use digital but it’s a lot lower quality. It’s actually exactly ten times less but there are advantages to digital in terms of sharpness, so it’s complicated. I guess it depends on the funding. There’s advantages, I mean in theory you can make an even better film if your equipment is lighter and easier to move and sees in the dark. There’s all kinds of advantages to that. I’m hoping that in the coming few years the quality of digital will catch up to film, it hasn’t really happened yet. Well, it’s happened in 35mm but it hasn’t happened in IMAX yet. But it might. It depends, I guess on the physics I guess, it’s a lot of data to store.

Here’s hoping.

Yeah. I’d like to mention that one of my favourite films is an Australian docudrama made in the ’70s called A Steam Train Passes. You ever see that?

No. I haven’t even heard of it.

Well it’s on YouTube. It starts in a roundhouse in the early morning and this green Australian locomotive pulls out and goes racing across the country. I saw that when I was 25 years old. It was always an inspiration for me because it was a poem. It’s not a drama it’s more a documentary poem and I’ve always liked that genre.

I see that A Steam Train Passes is a short film. You’ve done a few of those too, IMAX-made short films. We don’t get many of those screening at IMAX.

Yeah I like the short form, the short form is wonderful. 40 minutes isn’t too bad but ten-minute and 20-minute genres are fantastic. They’re harder to make – the shorter it is the harder it is – but they’re marvelous. Well maybe that will come back too when the prints aren’t as expensive.

That would be great. Thanks for taking the time to speak with me.

Thank you very much, I appreciate it.

Rocky Mountain Express is now playing at IMAX in Sydney. You can find out more and purchase tickets at the IMAX website.