Reflecting on Women in Horror Month, Kate Robertson speaks with authors Alexandra Heller Nicholas and Emma Westwood about the gender politics of Dario Argento, found footage cinema, the ‘Final Girl’ and more.

Kate Robertson: Hi Alex and Emma! Thanks for agreeing to this discussion on my very favourite topic, women in horror. I thought I’d start with a quick reminder of the project I’ve been working on for a few years now (very slowly it turns out): “The Man-Eater: (Cannibal) Femmes Fatales in Contemporary Visual Culture”. I’ve been removing and re-adding the word “Cannibal” for a while now. So I’m looking at representations of women not just in horror films, but also in new media like music videos and games. I’m interested in women who seduce and devour – literally, sexually, metaphorically.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas: Such a fascinating area of research, Kate! I love the scope of this project – and the broadness of your case studies. First thing it made me think of, interestingly, wasn’t moving image culture at all, but Louise Bourgeois’ Spider sculptures. Although I guess Denis Villeneuve paid such a mind-blowing homage to those sculptures in his phenomenal 2013 film Enemy that it all comes back to film after all? It always comes back to film!

Emma Westwood: Hi Kate – thanks for inviting me to join this most excellent roundtable with you and Alex. Was thinking, with your project, have you considered Luc Besson’s Leon: The Professional? I always struggled with the male gaze in that film – the Lolita-like presentation of a young Natalie Portman made my skin crawl. Interestingly, can you think of any ‘male Lolitas’? I cannot. The younger man seducing the older woman, maybe, but a sexually mature boy seducing an ‘innocent’ older woman? No.

Kate: Emma, that’s an excellent point, and that problem of the male gaze is a nice segue to Alex’s new book Suspiria, which considers Argento’s film through a feminist lens. This is not necessarily a standard point of view, could you tell us a bit about your argument Alex?

Alex: It is and it isn’t. The big clichéd, oft-cited quote about Argento and gender is this famous one: “I like women, especially beautiful ones…If they have a good face and figure, I would much prefer to watch them being murdered than an ugly girl or man”. Carol Clover famously uses this quote in her foundational book Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (1992) as a kind of shorthand to say “sure, look, some male horror filmmakers are clearly pigs”. That she cited a secondary reference and not the original source (an interview with Alan Jones for Cinefantastique in 1983) at first gave me hope that she’d perhaps taken it out of context, but no, in chasing down the original citation it was pretty clear that there was no ambiguity about what he was saying.

This is clearly a pretty uncool thing to say, and obviously any attempt to try to undo or excuse it would be pretty gross. However, my feeling is that critical approaches that insist on reductive, clear-cut binaries between “progressive” and “regressive” are not just simple-minded, but they often do more harm than good by shutting down discourse rather than opening it up. For my money, for example, Argento has made one of the most progressive and also one of the most offensive rape-revenge films I’ve ever seen: The Stendhal Syndrome in the case of the former (which I’ve written about extensively, particularly in my 2011 book Rape-Revenge Film: A Critical Study – and Kate, I know this film is a favourite of yours too), and in the case of the latter, the short “To Love and Die” from his 1987 television series Gli incubi di Dario Argento.

So ultimately, I don’t think it’s productive to try to stake an ultimate claim on his gender politics because I simply think the work itself forbids such clear-cut distinctions. What I am more comfortable with—and I champion this at length in my book—is instead of trying to unpick what (predominantly male) film critics have made of Argento’s gender politics, maybe it’s more fruitful to look at how women themselves have responded to his films. Fans of Argento (and Suspiria in particular) include the remarkable Japanese author Banana Yoshimoto and the iconic late US feminist writer Kathy Acker. Acker is one of my idols, and she adored Suspiria to the point that she dedicated an entire chapter of her classic book My Mother: Demonology to a reworking of Suspiria called – wonderfully – “Clit City”. Suspiria, Argento and Italian horror more broadly has been championed by the feminist film theorist Patricia MacCormack amongst many others, and Argento himself has said that most of his fans are women: I can say first hand just from personal experience that this is probably the case. Perhaps the most important, final word on the subject quite rightly comes from Jessica Harper herself, who considers Suspiria a female ensemble film, made up of a diverse range of strong female characters, where the very few male characters are there to fill in plot details: they’re certainly not romantic interests, the film exists well beyond those kinds of clichés.

Emma: Just like you, Alex, I’m a huge fan of Dario Argento’s work. I’ve got your book on my bedhead as we speak and I’m loving every word of it – us Suspiria fans thank you so much for writing it. You could say Argento was one of my ‘first crushes’ when it came to horror, despite being subjected to the savagely cut, Australian VHS releases of the ’80s. Inferno was the repeat watch for me, although Suspiria is right up there.

Alex: Emma, this reminds me of the pan-and-scan Australian VHS release of Deep Red that missed out on the important reveal of the killer’s face at the start of the film – you see it in the normal cut, but in the version that was available here for years, we had no idea that the killer was shown at the very outset!

Emma: Oh yes – that pan-and-scan version had ‘empty’ shots where the conversation was taking placed on extreme sides of the screen and the characters were subsequently cropped out. Sacrilege. When I finally got to see the widescreen, uncut version of Deep Red, I also noted the amount of dialogue that had been edited from the pan-and-scan Australian release – whole chunks of comedic exchange between David Hemmings and Daria Nicolodi – which really affected the tone of the film. You’d think more controversial elements (i.e. horror sequences) would have been trimmed to meet the OFLC classifications, but no, they cut dialogue.

Alex: Honestly, I’d be happy to do an entire roundtable dedicated to VHS aesthetics and the influence of things like pan-and-scan on the films that we saw here growing up – a subject I find eternally fascinating! But keeping the attention on Argento, I was almost relieved when I read that Argento himself found that the majority of his fans were female. Gave me a sense of camaraderie I didn’t expect…

Emma: It’s strange but I felt the need to justify my love of Argento to people – and, as a supposedly ‘normal’ young woman, I did find I had to actually justify, as opposed to explain, why I would love to watch something as gruesome and violent as a Dario Argento film, or anything termed as a horror film, for that matter. I’d say it’s because of the beauty of his films, everything about them – from the mise en scene to the production design, colour use, costumes, music. Watching an Argento film is akin to walking through an art gallery and being sucked into the works themselves.

Alex: Which takes us back to his film The Stendhal Syndrome from 1996, a film that does this exact thing in its opening ten minutes!

Kate: Alex I was thinking this exactly! What a glorious (and absurd) sequence. The art historian in me wishes I could experience that literal swoon.

Emma: Of course – yes, I didn’t even click to that correlation to The Stendahl Syndrome but that’s a poetic observation.

Alex: Argento loves art galleries – think again of The Bird With the Crystal Plumage. He gets that reflexivity between film and art very well: Deep Red’s reveal hinges on paintings and drawings, and Suspiria itself can be considered a giant, moving painting!

Kate: Yes of course, the attention to composition and carefully planned mise en scene – especially his attention to colour and light – is very reminiscent of a painting. I think that’s why I find his films so appealing: I can read them like a canvas.

Emma: I think my justification for liking Argento did little to convince my critics, though, other than make me appear weirder in their eyes. But yes, I can understand why the aesthetics of an Argento film would appeal to women and gain him a legion of female fans (like us). Aesthetics are something that I think women can generally connect with and appreciate fully, and Argento’s films are so beautiful you find yourself seeing glorious things in acts that should actually be repulsive. That’s how powerful he is as a filmmaker; of all filmmakers, not just the horror genre.

Kate: So, if we are thinking about the power Argento’s vision wields, I’d like to talk about the characters he draws. Let’s talk Final Girl. The ‘Final Girl’ is an obvious figure to consider when you think about positive images of women. What do you think about this character in film history? One thing I admit to finding problematic is that Carol Clover points out that this character is generally boy-ish – so, to be a survivor and a strong character, perhaps they can’t be especially feminine?

Alex: It feels almost sacrilegious to criticise Clover because she did such hugely important, foundational work – and her fundamental argument to me about gender fluidity and cross-gender identification in horror is as exciting to me now as it was when I first discovered it. But yeah, like a lot of horror academics of that particular generation, I don’t think I’d be the first to say that she was almost bit of a tourist – there’s some real skimming of the surface to look for points of similarity that just don’t hold up, some cherry-picking of case studies. For starters, she bases her argument around films like Psycho, Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 – none of which I would say particularly representative (or even typical) of the slasher genre more broadly. More problematically for me, I think the idea that the Final Girl is victorious just because she survives is frankly not good enough: if a “victory” is simply defined as not dying and (in the case of films like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Halloween) screaming and being covered in blood and probably destined to a living a life with ongoing PTSD, that’s hardly cause for celebration. That’s another really important thing that is often ignored with Suspiria – Suzy does more than simply ‘survive’. She walks away from the burning school at the end not just smiling, but beaming. Now that is a victory!

Emma: Totally agree. To just survive as the Final Girl is not victory. In some of these instances, the ones who perished – and perished early – were the lucky ones. I particularly liked the reworking of gender and gender relations in Jeepers Creepers – and I’m talking about the film on its own terms, not associated in any way with the personal morality of its director. Right from the opening scene, it turns slasher/stalker convention on its head: i.e. you assume the teen couple in the car are romantically linked and most likely rooting (hence, why they should die); you assume the male character will be the one who is constantly saving her from peril and patronising her when she is ‘hysterical’; and you assume the female character is, ultimately, the intended prey. These are all incorrect assumptions. The female character also gets to be the Final Girl, she takes on the hero role usually reserved for male characters and yet still remains very much a woman – not ‘boyish’ at all.

Alex: I could kiss you for saying this! I really like a lot about the Jeepers Creepers films, but bloody hell are they difficult to tackle in terms of what we know about Victor Salva’s status as a convicted sex offender. I think there is a really important queer aspect to the Jeepers Creepers films, but knowing what we know about Salva makes it extraordinarily difficult to talk about them like this. I salute you for being so eloquent about them here, and honestly, for even being gutsy enough to bring them up: that old chestnut about the ethics of liking work made by thoroughly reprehensible people is one that doesn’t seem to get any easier. This is sticky, icky terrain.

Emma: Happy to throw the cat amongst the pigeons, so to speak. I try to separate the maker from the work when it comes to art. Those waters can get muddy and, sometimes, the dirt is so dirty it can’t help but stick… But I digress, we were talking about the Final Girl.

Alex: Yes we were, and I hope I’m not sounding too negative or dismissive about Clover’s hugely important work here – I think from an academic (and probably just broadly critical) perspective, it really is the epicentre of the work I do in gender and horror. But it’s certainly not without it’s problems.

Kate: I completely agree with this, and of course Clover’s work is still incredibly useful. One issue I had when I went back and watched some classic slasher women, like Laurie in Halloween, and thought (maybe unfairly) that I really wanted to see less overwrought screaming and more taking control of the situation.

Alex: I love that era of slasher, and Halloween especially is a really precious franchise to me both personally and professionally. But yeah, Laurie, come on! Is just surviving enough to make it a victory? I’m in a minority here but I’ve always really championed Halloween IV: The Return of Michael Myers (Dwight H. Little, 1988) as the real hidden treasure of that series: the final girl is young—hasn’t hit adolescence yet—and how that film ends and where it takes her is somewhere really fascinating. Tony Maylam’s The Burning (1981) is also another really important slasher for what it does in this regard: the idea of an effeminate Final Boy I think is quite radical, especially in the context of what at first appears to be just a standard T+A slasher film.

Kate: So then, we’re back to the male gaze. Considering representations of women in horror, what do you both think about the problem of the gaze? Has the conventionally male heteronormative gaze been shifted? Can we re-think images of women that are objectifying?

Alex: This is where Clover’s real strengths were: I often think about her exquisitely framed statement that in horror, “we are both Red Riding Hood and the Wolf; the force of the experience, the horror, comes from ‘knowing’ both sides of the story – from giving ourselves over to the cinematic play of pronoun functions”. I think the gendering on the gaze is often deliberately volatile and ambiguous in horror, and often even subconsciously calls upon us to tease out the assumption of simplistic binaries like male/female and masculine/feminine. It gets a lot of flack, but I honestly think found footage horror was an amazingly fertile terrain to nut out a lot of the dynamics of the gendering of the horror gaze. I wrote a whole book on this subject in 2014, and I didn’t intend it that way but I just kept coming back time and time again to gender: the bulk of those films (although of course not all) have men behind the camera, and almost always the camera fails to capture or protect the protagonists from the horrors they encounter. At its best, found footage horror is about the failure of the male gaze – one marked through a reliance on camera technology. The fly in the ointment here is of course one of the most famous found footage films ever made, The Blair Witch Project, a movie that while I love it to death I’ll never quite reconcile in term for how determined it is to punish Heather for the ‘crime’ of wanting to be a film director.

Emma: This talk of male gaze recalls an incident, many moons ago, when I was making a short film with a former partner of mine. The female protagonist was presented for the bulk of the film as the hunted but, in the finale, we turned the tables and revealed her to be the hunter. I remember struggling to get the right performance from the actor for the finale. It just didn’t hit the mark in the way I wanted it to – it was too clichéd. In retrospective, the cliché was created by her playing up to the male gaze. It was only after we had wrapped for the day that I realised what had gone wrong: I needed to tell her to play the role as if she was a man. It’s as though all the patriarchal imagery of ‘assertive’ women (read: sexually aggressive women) that she’d seen all her life had infiltrated her subconscious so, when I directed her to act strong, she took that as being salacious. It wasn’t her fault – she was just copying ‘strong’ performances she had seen all her life in cinema – and I was neither insightful enough nor skilled enough as a director to correct it. But, in asking her to act like a man, I believe her performance would have resulted in, not a man, but instead a strong, commanding woman.

Kate: It is so interesting to be able to consider this issue from this vantage point of behind the lens of the camera. I also love this transformation from Final Girl to antagonist – films that shift the narrative are so fun to watch. This idea of found footage horror as a reflection of the failure of the male gaze is so interesting, because so often characters in horror are poorly rendered and difficult to engage with – found footage films are supposed to be more believable but they often suffer the same problem.

Alex: I think there are some really incredible found footage films – often quite radical, especially in terms of the ‘democritisation’ of production (ie: anyone can make one), but I think the glut of mediocre product really drowned out a lot of the more interesting, daring examples. I mean, in Australia at least, how many people have heard of Megan is Missing, Home Movie, Exhibit A or the found footage films of Kōji Shiraishi? The issues of authenticity and verisimilitude are really unstable across found footage history (if you consider that history stemming back beyond Cannibal Holocaust, at least). The real danger of these earlier variants comes from the whole ‘is this really real?’, but by the time we got to Paranormal Activity things like surveillance culture had become more the holder of the gaze – a kind of cold, institutionalised disembodied gaze, inhuman – and that’s what kept it alive. That these institutions, however, are often gendered male – and male dominated – is itself another area of interest. I’m not a huge fan of the franchise, but that first Paranormal Activity film in particular does extraordinary things with gender politics. Back on topic, there aren’t a huge amount of women who have made found footage horror films which I find curious, and as much as Blair Witch has an impact on me unlike very few other horror films (that ending still chills me!), I think it’s fair to say its depiction of women filmmakers is less than progressive.

Kate: What do you both think about the current work of female directors in recent films like Honeymoon or The Babadook? Do you think these films offer a different vision?

Alex: Honeymoon I really loved, and had a really interesting experience watching it: I knew it was directed by someone called Leigh Janiak, but I didn’t click that was a woman. When I found out afterwards it was not a male director, it actually made me rethink my take on the film: not dramatically, but enough for me to actually be really ashamed of my own tendency towards essentialism, the idea that women make certain ‘kinds’ of horror films. This is, of course, bullshit, and something I rally against, so it was necessary that I called myself as a bit of a hypocrite on this point, and I still feel really rotten about it. You only have to look at horror films by women like Kei Fujiwara, Mattie Do, Ursula Dabrowsky, Josephine Decker, Claire Denis and Mari Asato to make it pretty clear that trying to draw some kind of “women make horror films like X” is close to impossible. But, as Jane Campion said at Cannes in 2014, “It’s not that I resent the male film making, but there is something that women are doing that we don’t get to know enough about.” We need different stories, and women and people of colour need to be granted space at the table to have their range of different voices heard, even if those voices are telling us about killer clowns at Japanese theme parks.

Jennifer Kent, of course, is simply one of the shrewdest Australian genre filmmakers we’ve seen in years, male or female. Although it’s the only horror film I’ve ever seen that’s really successfully tapped into my own experience of motherhood, I hesitate to align that with some kind of essentialist ‘vision’ on Kent’s part: you only have to look at the praise she received from people like Stephen King, William Friedkin and Mark Kermode to know that this is no ‘women’s film’!

Emma: I really wish Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook had been released at the time when I was writing my Monster Movies book; it would have been a truly exciting and worthy inclusion – I mean, an illustrated monster… sublime! It’s so easy to fall into a trap of saying ‘women make these kinds of films while men make these kinds of films’ but filmmaking is such a collective experience that, even if gender perspective comes into the mix, it’s going to get diluted across the creative process. What if a woman is the producer, a man is the writer, another man is the director and another woman is the editor? Who is really making that film? Look at something like Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark or any of her non-horror films, for that matter. Does she make so-called ‘women’s movies’? Hardly. And this collective involvement can differ from one film to the next depending on how big the film is, whether the filmmaker gets final cut or works in multiple roles or operates as an ‘auteur’, etc. etc.

Alex: I’d also add here the absolutely inescapable influence of long-time Martin Scorsese collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker, or even the work of another editor, Margaret Sixel, and her incredible donation moving the visual language of action cinema forward in George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road. That’s a film about monsters of another kind, I guess, but Emma I know horror monsters specifically are your forte?

Emma: Yes, you guessed correctly there, Alex, I used the representation of The Monster itself as the fulcrum of discussion in my book – there was even a debate with the publisher about whether to call it ‘Monster Movies’ or ‘Movie Monsters’ – and, in general, I didn’t pay much attention to whether the films I chose featured a female monster or a male monster, or were made by a woman or a man either. Tokenism is something that really irks me and I didn’t want to represent female characters or female monsters or female filmmakers out of political correctness or ‘just because’. If the book was called ‘Female Monster Movies’ then that would have been a different story.

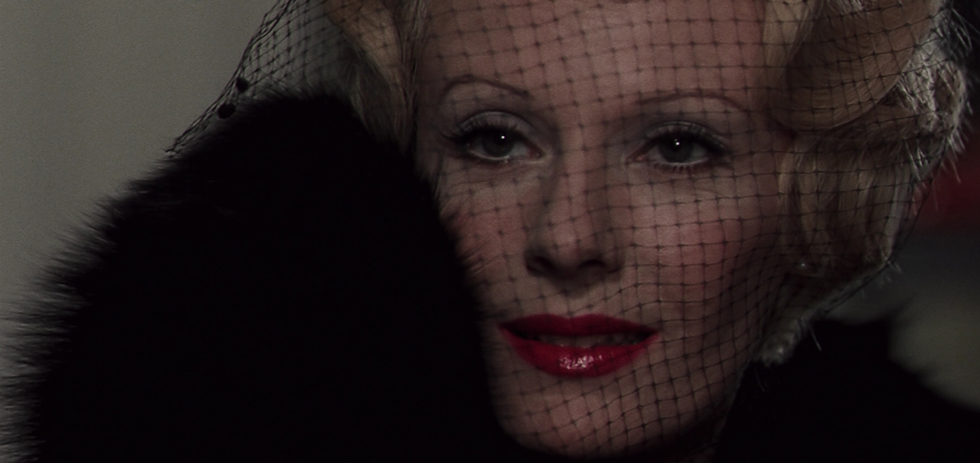

What struck me, though, was the lack of iconic female monsters in horror film history, given there are legions of female monsters out there not many have crossed over into mainstream consciousness like, say, Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, King Kong and Freddy Krueger; and gender-neutral iconic monsters like Godzilla and Jaws. The notable exception is Elsa Lanchester as The Bride of Frankenstein and, maybe, Medusa. Similar to her male counterpart played by Boris Karloff, The Bride is more likely to be recognised by people who would not normally watch the horror genre, which is what makes her ‘iconic’ in the broader sense of the word. And she only appears in the finale of the film for a few brief minutes, and is never actually threatening as a monster – au contraire, she is terrified of everything around her! Despite her brief appearance on-screen almost a century ago, it’s not uncommon to still find ‘Brides’ at Halloween parties with the tell-tale bolts of lightning zig-zagging up their mammoth, teased beehives. Dress up as Delphine Seyrig’s Countess Bathory from Daughters of Darkness and you’re more than likely to have people scratching their heads wondering who you are!

Alex: It’s curious to unpack how Barbara Creed’s notion of the monstrous feminine fits into this – I sense that there’s a really important distinction you’ve made that almost challenges her argument for the ubiquity of monstrous femininity in horror through the relative absence of literal female movie monsters from this broader pop cultural perspective. Honestly, off the top of my head the only other figure I could think to add to Elsa’s Bride of Frankenstein would be Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz!

Emma: Yes, of course, my aunt, the Wicked Witch of the West(wood)! I would not be so bold as to challenge Barbara Creed—she’s right on the money with the monstrous feminine—but there’s an inherent public acceptance of something when it crosses over into iconology. The iconic females in history – the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Bettie Page, etc. – are highly sexualised so the male gaze appears to be playing a large role here in making them ‘acceptable’ as icons.

Kate: I don’t know why Daughters of Darkness is not more widely known – I was surprised by how enjoyable it was to watch and Elizabeth is such a wonderful femme fatale. She should be an icon! Something that has struck me in my work is that female monsters represent in sci-fi horror – I’m thinking the alien in Alien, the ants in Them, the Borg Queen in Star Trek. This brings me to the last thing I’d really like to discuss: the monstrous mother.

Emma: The film that immediately jumps to mind when you say ‘monstrous mother’ is David Cronenberg’s The Brood – and what a film that is! It’s interesting because Cronenberg has been accused of fearing women’s genitalia, something he vehemently denies though. I personally feel Cronenberg uses his brand of horror – ‘body horror’, where the horror is derived from some form of aggressive mutation of the body – to show how powerful women can be. In The Brood, Samantha Eggar is such a powerful force she actually gives birth to her emotions (primarily, anger), birthing them in a physical form of dwarf-like creatures that then wage revenge on her behalf. Quite impressive work by her, indeed.

I’ve been looking a lot into David Cronenberg lately because I’m writing a book on The Fly for Devil’s Advocates (the same series that Alex has written Suspiria for) and I found this great conversation between Cronenberg and filmmaker Bette Gordon. He tells her he considers his films omnisexual rather than presenting perspectives down strict gender lines of male and female. If you look at The Fly as an illustration of this, it’s as though the male gaze has been reversed: the female protagonist is the one who looks on and witnesses the scientist’s mutation into a fly, even through a camera lens at times. The scientist effectively gives birth to himself, just as the ‘monstrous mother’ in The Brood gives birth to herself or, at least, her anger. So, as you can see from the juxtaposition of these two films, giving birth is something that’s not reserved for just women in Cronenberg’s world. He’s an equal opportunity filmmaker.

Alex: To say I’m looking forward to what you cook up with The Fly and Cronenberg more generally is an understatement, Emma – your monster book was extraordinary, and you have the rare gift of being a great writer as well as a great critic. This talk of The Brood leads me to another of the great ‘male directors working through an ugly divorce’ film, Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession from 1981. This is a very topical film, as Żuławski himself just passed away earlier this month.

As juvenile as it perhaps is for a professional film critic to have a ‘favourite film’, this is absolutely mine: the only Video Nasty to win an award at the Cannes Film Festival, Possession is just alive, its hysteria and energy just radiates off the screen. Żuławski saw the film as his way of working through a particularly nasty divorce, but lead actor Isabelle Adjani just bit and fought and wrestled and made it just as much her own – and if the rumours are true, it very nearly killed her doing it (there has for years been rumours that she attempted suicide after filming). If you’ve not seen the film, you’re in for a treat: in short, Adjani plays a woman who wants a divorce from her husband, and the film follows her desperate attempt to find a way to express herself. She feels defeated by language so turns to her own body to find a way. There’s an energy of pure gyno-fury in Possession that I have never seen anywhere else. Adjani lets her body literally go out of control, she totally surrenders to a kind of primal chaos that is both ultimately feminine and feminist as it is pointed explicitly towards her character transcending what she feels is a repressive situation. This scene in particular says more about female monstrosity – and, what Creed misses I think, the hugely cathartic, radical value of embracing, of owning that monstrosity – and that Adjani’s character is also a mother and that this is loosely a kind of supernatural miscarriage scene just speaks volumes about the kinds of issues we’re talking about here:

I can’t underscore how important a film this is when talking about gender and horror, and I finish with it today because this scene alone really challenges in a sense questions about male authorship: as a performer, this is as much an “Adjani” film as it is a “Żuławski” one. She turned this movie into something uniquely her own, and something that still captivates and holds its power over 35 years later.

Kate: This seems a perfect place to stop (though I think we could keep going, and going). Thank you both so much for this fantastic conversation!

Kate Robertson is not that kind of doctor. She teaches art history and film studies, writes about arts and culture and compulsively watches horror films.

Emma Westwood is a writer, journalist and lover of horror cinema from Melbourne. She is a former Arts Editor for street press magazine Inpress (now called The Music) and former performing arts columnist for The Age. She has written for the likes of Empire (Australia), Filmink (Australia), Fangoria (US) and Screem (US). Her cinema writing also includes the book Monster Movies (Pocket Essentials, UK, 2008) and she is currently working on a book for the Devil’s Advocates series on David Cronenberg’s The Fly.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas is a film critic, co-host of Triple R’s Plato’s Cave movie review programme and co-editor of the film journal Senses of Cinema. She is the recipient of the 2016 Award for Best Review of an Individual Australian Film from the Australian Film Critics Association, and writes books and articles about cult, horror and extreme cinema including Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study (2011), Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and the Appearance of Reality (2014), Devil’s Advocates: Suspiria (2015) and is currently working on a book about Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45 for Columbia University Press’s Cultographies series