Jan Gasmann’s Europe, She Loves offers an insightful reflection on the intersection between love and politics in Europe. The blurring of borders and boundaries in Gasmann’s work, along with the line between documentary and fiction, expresses political ideas through aesthetic choices, with a final product that offers a coherent and romantic look at the continent. We caught up with Gasmann at Sydney Film Festival to discuss the countries, couples and crises his most recent work navigates.

I wanted to open by asking what drew you to making a film about this idea of Europe and love, but specifically the cities in focus?

I think at the beginning for me, it was a moment where, on one hand, I have always been very interested in the idea of a couple-relationship – and then at the same time there was already all this politics going on. So for me it was an obvious choice to want to put those two things together. I also believe you can’t just have politics in the air and a personal life with nothing to do with it. So I decided ‘okay, I want to see what’s up with Europe’ in a way, because I live in the middle – even though Switzerland is not part of the European Union. There was a time where you heard a lot of stories in newspapers and magazines, and it was always about this sort-of “lost generation”. And at some point you just wouldn’t read anything about it, it was just gone, and it was like “what’s up now? Is everything fine again?”

So at that point I started working on this film and the cities I chose… at the beginning I was thinking “I should go to Berlin, I should go to Paris”, you know, like the obvious kind of choices – and at the end I ended up with the idea that I want to travel on the frontiers of Europe; like on the frontiers culturally, like Thessaloniki which has been Turkish and has been Greek. The same with Svertao and the Soviets and Talinn. So I chose places that I’d never been before. I went there for the first time for the casting. Usually I had like two or three phone numbers from friends of friends and you could send them a really long email about the whole project but it was really hard to explain this. But when I went there and I sat down with them they would kind of get the idea, and my energy, so they’d take out their phone and they’d say “this is a couple” and “this is a couple” and “meet them”. By the end I met about 100 couples in this whole kind of process, and also to find out what kind of movie I wanted to do.

I was curious about this, a lot of Europe, She Loves runs somewhere between a film and a documentary – the couples you shot, then, were actual couples. Were these stories written for them or were these stories recorded and edited?

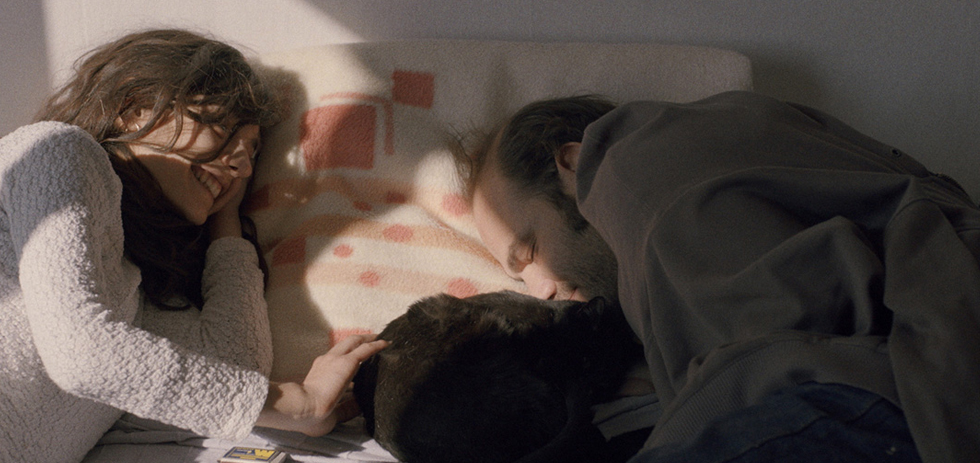

They’re actually couples, yeah. So the fictional part of this film is hard to describe. I mean, it’s a question that comes up a lot and I don’t have the perfect answer to it. We lived with them, and I was shooting 12-14 hours a day, so there was very little directed in that kind of a way like “do this” and “do that”. But then at the same time, in the way of editing and putting stuff together, it has a sort of fictional feel to it, or the its being filmed and how we portray them. So I think it’s in between those two things. But for me the difference between fiction and documentary is not so important.

Yeah –

It’s something that came now when the movie was done. When it was released people had to put it in a box, that’s their job – so, okay. For me, I also worked as a cameraman on other documentary films and we’d tell people to walk from here to there; with this this it was more like “we missed it, let’s try and get the next image.” So we didn’t try to put them somewhere, you know?

It was definitely interesting to see this grouped as a narrative film, despite being in a certain way very alike to a documentary.

I think it’s also a thing where there’s very little documentary films on love, or love-related, without any ‘experts’. So I think the kind of narration you expect is more from a fiction film, because a fiction film is a lot about love, so you get the same sort of triggers.

Definitely – and moving the stories outside of Paris and Berlin, or major European cities in general. When you were talking about the frontiers, are you talking geographically in Europe?

Yeah, from Switzerland you would go to Seville, then up to Dublin, then we drove all through Sweden to Estonia – on the Russian border – then down the East to Thessaloniki; then through Italy back to Sweden. So we basically did the round… and the whole trip by car.

One of the other things that links the majority of the countries you shot in is the degree to which they’ve been affected by the crises in the last decade – was this kind of at the centre of your mind when you were looking for these locations? It definitely becomes a major part of the film.

Of course, that was right at the beginning. I think, also at first, I was thinking more in a topic kind of nature… I would say “I need a couple that is facing big debts” or this and that. I also spoke a lot with activists as well. But I realised a lot through the casting, that it was more than the poorest of the poor affected by the crisis. Even if you look at the middle class, there’s no future for them. Like if you think about Spain, they studied… but they do about 10 jobs at the same time to get somewhere. So I moved a bit away from the explicit idea that the political aspect has to be so strong, to more of the intimate aspect. I think that this kind of feeling that they have, is that if there’s no future, if it’s not open, it’s really hard to live a relationship as well.

The way in which the scenes would bleed from these intimate moments within a relationship into a protest in the street was very effective in portraying that. Since we’ve got to wrap up, I’m interested in how you feel about the way Europe has been constructed on film – and how you think Europe is going to be viewed in the future in this sense?

Well I think in Europe, there’s not a kind of European identity so far. We all have these strong cultural backgrounds – also with immigration, to places like even Australia. With Europe, there’s something to be done about that, without losing that background. Right now, how it is, the democratic involvement of the people is really low. So basically, this whole continent is ruled by some leader from other states or just economic pressure on what you have to do. If I had to think about a positive, optimistic, portrayal of Europe in 10 years it would be that people actually get more involved and get to talk with each other. I think that the open borders, to be together, to work together… I think that’s something really strong. The movements we see now, the right wing movements where everyone goes back to the nationalistic level, are very dangerous.The European Union is 20 years old; it’s very little, so it’s too early to just say “let’s just be French again” or “let’s just be Polish again”… for me I think it could be another 10 or so years for us to be European before we abandon the whole project.

I think your film definitely plays into that idea with these tensions and growing pains shared by that European idea as well as the couples you focus on – and I think that Europe, She Loves does a great job of articulating those concerns. I think we’ve got to wrap up but thanks so much for the chat.

Thank you.