Oliver Hermanus’ The Endless River, the third from the South African director, is a slow-burning work that offers palpable reflections on the notion of violence. Tension and restraint are paramount features of the work, with the nuance that has defined Hermanus’ previous films as present as ever. From the mindset of Afrikaner society he depicts in Beauty (Skoonheid), the class divisions of Shirley Adams, to the rural side of South Africa shown in The Endless River, Hermanus’ decade in filmmaking has been unique, challenging, and distinguished. We caught up with Hermanus at Sydney Film Festival to discuss his most recent film, working within South Africa’s film industry, and the way his experiences within the country have shaped his own approach to filmmaking.

It was interesting to watch The Endless River after seeing Beauty [orig. Skoonheid] a few years ago, and being familiar with the subject matter of Shirley Adams. As three films that are very distinct in their concerns, style, and what they want to say on topics like inequality, perceptions, tensions in Afrikaner culture, and in your latest work this constant idea of violence — what informs the process of you choosing a topic to cover, and how you build these stories?

I think it changes from film to film, and also it changes depending on where I am, or my age perhaps – which was a big influence on Skoonheid. And I think when I make a film, it’s because I’m making something that’s the opposite of what I made before. In terms of the subject, they each function as portraits. So that’s kind of what binds them in some way: the perceptions of realities of different South Africans who could be living at the same time, who do live at the same time in the country, but their universes are quite separate. So if you compare the three of them, it’s trying to generate that understanding of how complex South Africa is. And I haven’t even made films about the lives of black South Africans, and that in itself is going to be a completely different world.

Filming these opening scenes in your most recent work, there’s this tension established so quickly, both in the dining room and in the second scene in the robbery. As a director approaching that kind of scene, how you choose to film or capture violence in a way that you do throughout The Endless River?

Well, producers will always freak out about those sorts of scenes, because they’re always so scared they’re going to effect the audience in a bad way or be labelled as too brutal. But because I had done a sort of rape scene in Skoonheid, a lot of this was trying to do something else. A different way of trying to demonstrate horror, or suffering, or terror, but not in the same way as I did before. I was looking for a house where the camera could move around in a circle, which is related to the sound as well. The base idea was to be able to float between seeing the violence, to leaving it, and coming back to it – so we did shoot it in one complete take.

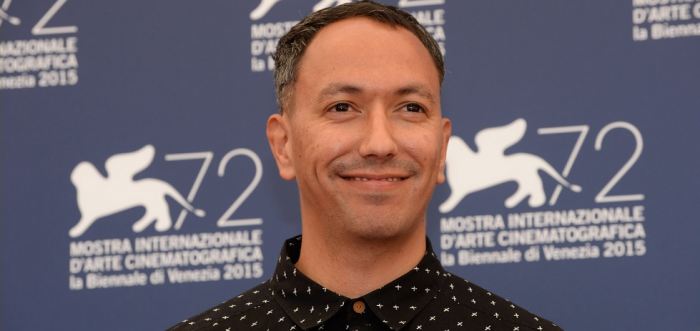

With the lead actress, Crystal-Donna Roberts, she was the first South African Actress to be nominated for a Golden Lion.

Yeah, because we were the first South African film to go to Venice.

What was the process like of working with her?

It was good. She’s very hard-working, she’s very trusting and never says no to anything. She took all the risks that she had to take. For me, working with an actor is about a relationship where the actor is prepared to jump off a cliff blindfolded, and she did. She would never resist any of my instincts to push her emotional state to a limit.

In your approach to film-making, I read an interview where you pushed back against the idea of being the “first South African auteur” and the idea that you would be making a film in regular intervals, rather than at a pace that felt more natural…

Yeah, the industry in South Africa is very small, and the fortune of being an auteur is that you can make films for five people and you will always be funded. But the only reason auteurs exist in Europe is because they’ve got infrastructures that afford them. In some senses the word “auteur” just means “author”, and so I definitely see myself as a filmmaker who chooses what he makes, and it’s connected to me in some way. So in that sense I do work that way, but I wouldn’t want to be like Woody Allen, I think, where for him it’s just habitual and some films are good and some films are not. I think probably just because of being from Africa, you spend so much more time convincing people to invest in your work that you can’t really take the risk of making sub-level stuff.

Is the structure of the film industry in South Africa quite scarce?

There is funding for work, but the government is more interested in trying to kick-start an audience and commerciality. So they’re trying to fund what they think is important, which is genre; very straight comedies, romantic comedies. No one in South Africa really has an understanding of complex cinema. The government is not going to have very intellectual conversations with directors about their work in a timeline of cinematic art. They’re going to just be like “okay, it sounds like a rom-com, let’s give you money” – and they don’t give a lot of money. So we’re just producing a lot of low-end genre films that they’re hoping will stick with the audience.

Does that effect distribution within the country? How widely is your work seen in South Africa?

I think now the work is seen more, because the more you make the more the international attention arrives. That then gets publicised in all the South African media, and then people become aware of me, and then at some point when that movie comes out they’ll just remember it from “oh, that was that movie that was in the newspapers for a long time, we should probably go and see it”. But I don’t think it attracts a mass market at all.

How is your work perceived, then, in South Africa? I remember when Beauty came out, there were some reactionary responses from certain communities –

Just purely because of the content.

How has a story like The Endless River [been received]?

It only comes out in three weeks, so we’ll see. But you have to have very limited expectations, you know? South Africans go to the cinema to escape, and this is not escapist cinema. It’s very hard for them to go to the movies and then be entrenched in something that feels very real to them, maybe because it’s obviously got certain attachments to their own reality. It kind of goes against the grain of what South Africans want from the movies, so to make this kind of cinema is counterproductive to being famous and rich.

For your writing process, are you inspired by certain issues or do you have a more instinctive approach in the film-making process, with messages implicit in your movies?

I think certain messages come out of them as you construct them. The more you work on scripts, the more you sort of think about things. South Africa is a country full of constant criticism, and the country is very critical of itself, especially now. Everyone is very opinionated, so if something happens the backlash can be huge. It seems like a lot of the urbanised part of the country spends a lot of its time just creating wars on social media about someone who makes a racist comment. It’s very easy to make a wrong move if you’re in the public eye as a politician, or a sportsperson, or anyone who makes a comment on their social media. You can become notorious very quickly.

This is constantly happening in the background, so when I’m working sometimes you think about certain incidences that you’ve heard about, and they sort of become subtextual in your brain. Particularly with the police in this film, there are two kinds of police. There are the black police officers that the French character physically attacks, but just because he doesn’t seem to trust them or believe that their doing their job properly. Where he gets this can only be from his own assumptions about them. Then the white police officer, who feels obligated to help him more than he’d help another South African, but his help is often misplaced and wrong, and causes more problems. And the way that that same white police offer helps her is very different to that as well. South Africans… our relationship with the police is always very fraught, and you never really feel like they’re there to protect you. You almost feel like you should be very suspicious of them.

Thinking back to Beauty and the sectioned off neighbourhoods, there’s this sense of division that your movies capture quite starkly…

I think this country… the geographies of these cities is still quite like that. Shirley Adams lives in a slum in Cape Town. Certain South Africans will know that that’s their understanding and that’s their reality, and they will see it and they will believe it – and then white South Africans will watch that film and have no reference to that. In Skoonheid, white South Africans will have complete reference to his world, but black South Africans won’t. In Endless River, you’ll have coloured South Africans who will look closely at the rural parts of that film and understand it, but again, black and white South Africans won’t necessarily.

I feel like a lot of South African cinema is built on a lot of this tension…

Again, there will always be criticism of a filmmaker where if you’re a white filmmaker and you make films about black people. That’s sort of something that becomes very problematic these days, because it’s a kind of trying to reform so much about how history has told narratives, and told stories. The industry right now is complex, because white South African filmmakers who want to make films that they feel are relevant to the world about South Africa assume that has to be about black people. So they make those films but then they’ll get criticised by South African black people who are like “why” – because I do question it myself. I wouldn’t say any three of my film aren’t connected to me personally in some way. Purely based on how I wanted to make them, or why I made them and why I wrote them. But I do find problems with white directors who have no relevance to the worlds that they tell on screen. It’s more like they’re using them because it’s what they assume it will attract international attention.

Yeah, where it becomes a certain ego-driven –

Ethnography. It’s colonialism in some weird way, because they don’t see it how they sort of are South African. But there are realities for white people South Africans, they have their own stories to tell, they are part of a society. So I don’t know why they wouldn’t be introspective and tell stories that are [from] a more personal place. Directors making films about black surfers or gangsters or, I don’t know, something that just seems so far-flung from their realities. I think that a lot of South African directors still make work that is essentially ethnographic. They’ll read a book, they’ll empathise and they’ll want to make it into a movie. I suppose it’s also a training thing – they don’t have training to know that they have to find an emotional centre that resonates with them personally. It’s a question of honesty. I think a lot of directors don’t realise they need to be exposed in their films as much as their actors.

Do you think there’s any change in this trend happening or not?

Well, technically it wouldn’t be because the government isn’t necessarily encouraging directors to be introspective. It’s like make a version of a Drew Barrymore film, or a cheap version of Sex in the City or something.

I find the structure of South African cinema so fascinating in that way, where every film I’ve seen from there has been so…

Different. (laughs)

Yeah… and it’s always grouped as South African cinema when it’s at a film festival or something, but –

They also don’t interact a lot, the directors, that’s very strange as well. Like, Johannesburg and Cape Town are separate cities and… I don’t know if you have that in Australia, where you’ve got a Melbourne scene of film directors and a Sydney scene of film directors, or if their work ever relates or if they ever really interact, because we don’t interact.

Looking at your history as a director, it seems like you mull over ideas, and they evolve in quite a natural way over time. Where do you see yourself going cinematically as a director from here?

So this film is set in the Western Cape, which is an area outside of Cape Town. I want to make another film set in a different part of the province; a film that’s about this festering anger that South Africans have, which is basically the product of twenty-two years of democracy and everyone feeling like not enough has changed in their lives, and that they’ve sort of given up on the hope that it will get better tomorrow. And they’re sort of now just… angry, and annoyed, and violent. It’s almost as if all the fears that we had when the country changed in ’94 – which was sort of put to bed because we never had a civil war, we never had mass violence, we sort of all just got along – all of that seems to now be rearing its ugly head. We’ve discovered it’s a delayed reaction, not we necessarily extinguished that reaction.

So that’s kind of where my head is at. You sort of find yourself being angered by everything; angered by still encountering racism, or corruption, or just all those things that South Africans swallowed whole, like this assumption that we were a rainbow nation; that we were this perfect integrated country that was an example to the rest of the world about reforming terrible state laws. I don’t think the headspace of South Africans have changed.

I feel that’s quite a recurring notion with lots of colonial nations. There’s definitely been this popular discourse in Australia where there’s a huge ignorance towards the ongoing injustices, especially in regard to the indigenous population.

I mean, I don’t know how vocal the indigenous people of Australia are – how much presence do they have in the headspace of the average Australian? How much media do they own? How much access does the average person have to works that are for indigenous people and indigenous languages?

They’re very vocal themselves, but the media landscape in Australia is very heavily controlled by groups like News Corp.

That’s very dangerous, because in South Africa it’s similar. I mean like, you’ve got the white population is 5%, but they own all the media. So all the movies, and the majority of genre films that are being made for publish, are for Afrikaans white people.

I read that statistic this morning, and from a lot of the films I’ve seen out of South African, I was honestly quite surprised by how small a number it was for how much control there clearly is over these industries.

And remember the white population is divided into two: you’ve got the Afrikaans white population and the English white population. So the Afrikaans white population, which is the more wealthy… the biggest media companies are Afrikaans media companies. I mean, they’re a percentage of that 5%, 4%. If you look at the magazines themselves, and you look at the biggest TV studios. It’s all of that media for that small population. Those things are angering people. You can still see so many things that haven’t changed. You can still see that coloured people… ’cause I’m coloured, so you don’t have a legacy of media ownership. You don’t have streams of TV shows and cinema and art, being produced by generations of coloured artists, whether that’s in a formal fashion or whatever. So you still have to kickstart non-white creative work, because there’s no legacy of it.

I feel like The Endless River definitely conveys so many of the complexities you’ve spoken about today, and I hope it does well at the festival. I’m excited to see what you do next. Thanks so much for your time today.

Thank you.