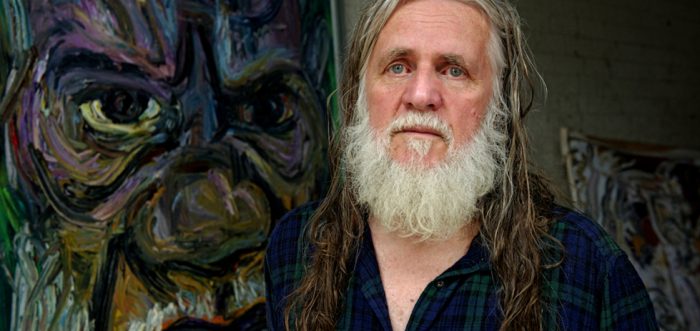

Not long after we launched 4:3, we spoke to George Gittoes at home in the Rockdale Yellow House, during the process of filming what would become Snow Monkey. At 66, Gittoes’ has continued to work with a frenetic sense of energy and ambition, maintaining a particularly unique approach to documentary filmmaking. From the first film of his trilogy, The Miscreants of Taliwood, the more upbeat Love City Jalalabad, to the director’s latest effort – both the most accomplished and wide-reaching of the three – Snow Monkey.

This conversation was conducted over a year ago at the 2015 Melbourne International Film Festival, however, the recording was misplaced for several weeks after the festival had concluded. With Snow Monkey now having played both internationally, most recently returning to Australia’s shores with Brisbane Asia Pacific Film Festival, we have decided to publish it – although, with this consideration, there are several marked parts throughout the conversation that refer to situations that are markedly different, and individuals who have since passed away.

In this, our second conversation with Gittoes, we spoke about the loopholes of funding in Australia, the shifts in approaches behind the scenes over the last several films, the dangers they face, the political landscape of Afghanistan, the manner in which the country is covered abroad, and the director’s vision for the future of the Jalalabad Yellow House and the filmmakers and artists in the country that have associated themselves with it.

It was really almost impossible to agree to be in the [2015] Melbourne Film Festival because we needed to work 20 hour days to get it finished—but it’s good to have a deadline—and the way we work is to edit a film, but still leave all the stems open; the sound stems and the editing stems. After watching it with two festival audiences, we’ll go back and change it. I showed a bit of it the other day when “I Witness” opened in Queensland—and there was one moment where I noticed people getting a bit distracted, and that was quite early in the film… so I took it out.1

I’ve done that with all my films. With Rampage, we did that at the Berlin Film Festival and then we made cuts. Then with Love City… there was a big mistake in Love City. We showed it in Sydney Film Festival and it went down well, but Nick and I could see a huge flaw in it.

What was that with Love City?

Well… the Norwegian film producers really insisted that we changed the beginning that Nick and I had, and put in something about me as a frontline war journalist—so we put in footage of me in Rwanda and cut that into footage of a riot in Jalalabad, over the Americans burning the Qurans. What I know about films is you’ve gotta let people know what they’re watching in the first 10 minutes, and Love City is a fun film; it’s about having fun in a war zone, and making films, and having a circus tent. This was sending out the message that this was like a Michael Ware movie, that was some frontline journalist thing… so we got rid of it all completely and it started winning awards and people started loving it a lot more. I think that’s the biggest mistake I’d made with a film. It recently won the Winter Film Awards Indie Film Festival in New York.

You’ve been able to get funding from Screen Australia for Snow Monkey. How significant was this in helping make the film in the way you envisioned it? It seems like a fairly major piece of funding to receive…

Well it was a thing called the Signature Fund, and you’d have to research this but I believe they’ve gotten rid of it now. But the idea of it was… it was a fund to encourage—I think Tom Tobruky and David Bradbury got one—adventurous film making. I don’t know enough about it, but I think they’ve gotten rid of it now. And it was a huge risk for me because the Screen Australia funding was $200,000 and the film budget was $500,000 so I had to guarantee a lot that myself. Fortunately, Fritt Ord—the Norwegian Freedom of Speech Foundation—has come in with money for the grade and the expensive parts of post-production. There was a big risk… if Fritt Ord hadn’t come in, I would have been paying the bank off for next 10 years.

The problem with Australia now, if you don’t get a pre-sale, is that SBS—the only real venue for a film like this—are only offering a few thousand dollars, which is basically nothing. And I’m currently having my own little war against SBS, saying that in years to come historians will see them as responsible for destroying independent documentary making in this country by saying we’re only going to help the few that get the pre-sale. The difference is: the people who get the pre-sale have to do a scenario that the television stations like and it’s still just a scenario. The people who make independent documentaries are prepared to run huge risks for something they believe in—when they deliver it to SBS, it’s a finished product. There’s no more gamble. So I know as a filmmaker, you can put up something that looks good on paper and it can turn out to be a very poor quality film. So people who are willing to run huge financial risks themselves are being penalised, and only the people who can put it through their vetting process—which is what it is: agreeing on a pre-sale—are getting support. Then SBS will say “we supported X number of pre-sales, we are helping independent filmmakers”—that’s not true. They’re helping establishment filmmakers who are doing films that can get past a bureaucracy and get a pre-sale, and usually they’re on subjects that are in line with editorial policy at SBS.

I can definitely see that…. especially with something like Snow Monkey being such a challenging film. I remember you were saying ABC called Love City Jalalabad a “re-run of the hippie era” and you wanted Snow Monkey to be a return to that style like Miscreants of Taliwood.

In documentary worldwide, I’m seen as someone who pushes the limits and does new kinds of films. When I did Soundtrack to War it was seen as a new kind of film, same with Rampage. And then Miscreants… it was an unbelievably experimental kind of film. And we got it on SBS, but it was hailed around the world in the same manner as The Act of Killing was a couple of years ago: it was a new kind of film. With Love City, part of the problem was running the only film and art school in Afghanistan. So it was very much a film about the people at the Yellow House who are all learning to use cameras, like Neha [Ali Khan] who makes film for the first time. So it’s more of a film as a model for what art can do against the military. I wasn’t trying to make a film, in a sense, for myself—pushing the boundaries. But with Snow Monkey, my whole Yellow House group had reached a level of incredible maturity. So that Waqar [Alam], who I trained as a cinematographer, is now better than me. He’s got the main cinematographer role. They’ve all been to Australia, they came and saw Love City at Sydney Film Festival, and the whole group has matured. So it was time to do a Gittoes-style documentary with a totally Afghan crew.

If you look at the ‘Dope Fiend’ scene, the cinematography is incredible—you can see right down into the bag where the guy is picking up the bloody needles. To shoot that, Waqar had to actually lie on the filth of the rubbish tip, and get down on ground level; it’s really inspired cinematography. So really, Snow Monkey has this whole group I’ve worked with coming to maturity.

There’s a certain trajectory that comes with framing the films as a trilogy, with Miscreants creating that opening in Pakistan, to the upbeat shift into Jalalabad with Love City, to this broader consolidation of it all with Snow Monkey—with this central tenet of the power of art and cinema running throughout it.

In Love City, we tried to make a better quality kind of Pashto movie than what we were making. In the two films I made in Pakistan, with a lot of the same group, I tried to move them away from the action-violence stuff. Then in Love City, we start making films for women, with women characters that men will watch. You can’t put a gun to a Pashto man’s head and tell him to be kind to his wife. But if he’s watching movies where she gets inspired within her own home, and he watches them with her, you’re able to persuade them gently to get their children to go to school.

The huge multi-million dollar effort of Australia in Tarinkot has been a complete failure. The Taliban have moved back into Tarinkot, the schools have closed, the hospitals have closed. So the gun solution doesn’t work, but we’re still in Jalalabad and we’re still doing stuff. But I think the next thing we’ve got to do is use all of the talent, with me on board to work with them, to make a fantastic, world-class feature film in Afghanistan. We’ve got the computers and everything else. My dream is to see Neha, Amir Shah, and the kids to be walking up on the stage for Best Foreign Film, and I’m hoping I’m not even involved. Neha and Amir Shah have both been to Australia, and I’m genuinely committed to seeing this thing through.

I think when I was at the Rockdale Yellow House, when you were living there and we spoke last, I remember meeting Amir Shah very briefly. He was very jet-lagged, walked outside, and then came back inside and announced that he had to go to sleep again.

And Neha would’ve been there too—and we’ve got Waqar here for the Melbourne Film Festival. I’ve just won the Sydney Peace Prize, so we’d like to get as many of them out as possible for that in November, and then we’d all go back together to the Yellow House. Including the old Sufi, we’d like to bring the old Sufi out.

I thought one of the interesting things that has been present—I guess, in most of the things you’ve been doing, but especially in Snow Monkey—has been this focus on the children in the community. Throughout this one it was really special how close and constantly you were working with them and inspiring them.

What happened was in Love City, we took the crew out into the outer areas. We discovered that these children, because of Taliban influence, hadn’t even been told fairy tales. They’d never seen film and they were not getting educated and everything else. So we made that film, where we had the little girl, the kid, which was our first children film. But in reality, what happened in the film happened. I got back, and we’re going to try and do something about the switch-over of power, with the end of the Americans and stuff. We’re interviewing all these people, and constantly, there was that horrible ‘Happy Birthday’ tune going past and cutting into our things, so we’d go out and tell the kids to go away, and we film… Then I finally decided to get to know them.

So that’s not made up. That’s actually how it’s went. So they hijacked us and got our attention. Then I discovered that they’d had to find their own money to get a franchise. So they have to rent those carts they have, and they have to invest in the ice cream machines. They don’t get given them. So it’s like a little mini-McDonald’s franchise, you know what I mean? So they’ve had to work on all sorts of jobs to get that because their parents have nothing. So in a way, the ice cream boys are… It’s like a selective process. They are little entrepreneurs. They’re very intelligent. They’re not going to school, but to get that together, and they’ve gotten that together on their own without any help, you know what I mean? So when we finally got them to go to school and IQ tested, every one of them had way, way, way above average IQ. The great moment, although it’s a very sad moment for me, is that when the terrible bomb went off and all those people were killed—

Near the bank, was it?

Near the bank, yeah. Well, Kabul Bank is next to the ice cream store and everything else. It’s the centre of town. It’s only a few blocks from the Yellow House. All of our kids were there, and thank god none of them were killed, you know, in that vicinity. That’s where the boys go to collect their ice cream stock and stuff. It’s where Steel and stuff go to pickpocket people when they come out of the ATM. Zabi and Salhudin, we were off doing something else. Rushed around and got the cameras, and they filmed that terrible stuff. I’m amazed I got back in time to shoot the interview with Zabi. By then the police weren’t letting us get near where the bomb had gone off. Zabi says, “well, this is why I learned camera work because I want to be able to do… show the world what’s happening.” He got that story, what he’d shot, onto Afghan news. So he’s only 13 years old, that’s pretty good isn’t it? So he’s already seeing himself as a professional journalist, and of all the kids, he’s not missing school. He’s working incredibly diligently and he’s got amazing ambition.

In his case, his father had been shot in the face by an American shotgun, lost his eyesight. So normally his father would have sent him to school, but Zabi, the oldest, had to go out and work to keep them fed. There’s no social security in… The Americans should compensate for people they do that too. In reality, if it was America, and cops went in, they break into the wrong house and they shot someone, they’d be in a lot of trouble. They’d have to compensate that family. But in Afghanistan, they just don’t even take them to hospital. If you saw that movie, Lone Survivor, the American one… In the end, the American’s been shot and so has the Afghan. The helicopter comes to the American, and he says, “Oh, but you should take my Afghan friend.” The chopper says, “No way. That’s not going to happen.” Well they would have shot Zabi’s father in the face and just left him there, more or less said, “oh, we made a… we fucked up. We fucked up.” Moved on. So it’s interesting. His father is a good man. So even though his father’s been blinded, he has got that family support. They’re in a more rural area, they have got a bit of the farmhouse. So he could end up being a great cinematographer.

The problem for Hellen and I is that we’re completely emotionally tied to all of these people from Steel to Zabi. So we have to get back there and make sure everything’s going well. This is an incredibly dangerous time. They’ve just announced Mullah Omar’s been killed. A lot of the Taliban are switching to IS, and the good Taliban are fighting IS. The new leader of the Taliban, Mansour, has always worked… he’s Pakistani and has always worked with Pakistani Intelligence, ISI. It’s the Pakistani Taliban who send death threats to Hellen and I. Like formal ones. So it’s a dangerous time for us to be going back, but we’re going back. But when we’re there, we upgrade the social awareness of all the people we’re working with, because I’m old and the police commissioner and all these people respect me. So in a sense, we create an umbrella of official protection for everyone in our group. When we’re not there, that starts to disintegrate.

You’ve spoke to members of the Taliban when you were filming this, correct?

Well, we are. The official leader of the Taliban for our whole region is Mullah Haqqani, and he’s in the movie. The good Taliban, in my opinion, are really good.

That involves him, or is he—

He is. He’s good Taliban. The great thing for us is if Jalalabad reverts to Taliban, he will be the leader, and he has endorsed the Yellow House. So that’s great for us. We feel that even if there’s a change of power to the Taliban, all the work we’ve done won’t be lost. His endorsement extends to the fact that two of his sons come to the Yellow House to learn editing. So there are good, reasonable Taliban, and all the world propaganda has tried to make them all… tar them all with the same brush. The irony is that America and the world will now be looking to the good Taliban to fight IS, prevent IS taking over Afghanistan. If IS took over Afghanistan, it would be one of the most destabilising things in the world because they’ve got a huge number of supporters in Pakistan. From Afghanistan, they could work on Pakistan. Pakistan’s got nuclear weapons. So these people that Australian and American soldiers are killing, we’re going to have to be… already, we’re trying to talk to them about being allies against IS. I’d hate to be an Australian family whose son or father or brother was killed in Afghanistan fighting the Taliban, and then within a few months read in Australia that we’re counting on the Taliban to fight IS. You think, “Well, my son or brother or father lost his life for nothing.” That’s sad.

I was interested in what effect the election of Ashraf Ghani was having on the region as well. Because—

Ashraf Ghani is great. We support him. You couldn’t get a better qualified man to run Afghanistan. Everyone at the Yellow House who could vote voted for him, and generally Jalalabad is pro-Ashraf Ghani. Even Haqqani, the Taliban leader’s pro-Ashraf Ghani. So in our region, there’s no question. Even if you’re talking to the Taliban, you can praise Ashraf Ghani and they’ll agree with you. So the reasonable elements of the Taliban want to function with Ashraf Ghani. If we don’t want to see war in Afghan… the worst thing that could happen in Afghanistan is that the peace talks between Ashraf Ghani and the Taliban break down, and the Taliban start fighting Ashraf Ghani. Then there’s that old saying: “divide and rule.” Well, they’re fighting each other, like what happened in Syria between Assad and the democratic forces: in the fight between two legitimate groups, the bad guys move in and… sort of stab them in the back kind of a thing. That would be a terrible thing, so I’m hoping that that won’t happen. Ashraf Ghani studied at Columbia University. He toured at John Hopkins and California University . His focus is on “Fixing Failed States”… There’s no better person in the world who could… His wife’s a Christian, and his daughter’s an artist in New York. You just couldn’t approve of more, but the Americans were backing Abdullah Abdullah, who was only half-Pashtun. That might be nice, but the political reality is that the majority of people in Afghanistan are Pashtun and they’ll never vote for someone who’s not—

A Pashtun.

A full Pashtun. The great thing about Ashraf Ghani is that he wants to do even more for the minority groups, the non-Pashtun groups than Abdullah Abdullah would. Abdullah Abdullah just wanted to help the people from the Panjshir where… he’s from that area, whereas Ashraf Ghani’s got a national view of helping all the minority groups in the country. So he’s good. What’s actually happening is lots of provinces… The thing that America created was unsustainable. It trained the Afghans to have one of the largest armies in the world, and they didn’t develop any other aspects of their economy. So once they left, there was no way that the new government could fund an army as big as that.

So lots of the provinces, the soldiers are earning nothing. They’re getting no food, you know what I mean, and it’s coming apart. So in those areas, when the Taliban walk in, they have a meeting. They don’t pull out guns, and they say, “you’re married to my wife’s sister and we’re not really enemies. We don’t want to kill you. Just lay down your guns and go back home.” That’s what’s happening all over Afghanistan. The unpaid soldiers, government soldiers who’d been trained by the Americans are laying down their guns and walking away from their police stations and their fortresses and the Taliban are coming back. It’s quite likely that could happen in Jalalabad where we are, and I would not imagine it would be a military thing. I’d imagine they’d all sit down and have jirgas [a term for an Afghani tribal council], and come to the conclusion that the national government’s not working out and they’re better to have Taliban rule.

The tipping… There’s this lovely term that’s come into popular culture these days: “the tipping point.” “Tipping point” this and “tipping point” that. The tipping point in Afghanistan is always corruption. There’s a point where corruption sort of metastasizes and becomes like a deadly cancer in a society. So the majority of the people don’t want the Taliban, but under a weak government, when corruption becomes too much for anyone to function, then they ask the Taliban in, because the Taliban do get rid of corruption. That’s always the fear.

I can see that beginning to happen everywhere in Afghanistan, where jobs are not going to the right people. The last election was fixed. Even though Ashraf Ghani won, the representatives in different areas paid for their victory. They just paid electoral officials to misread the vote. So our concern is not… I think I’m doing my job at the Yellow House, as a person who wants to see an art centre there and a place where all these creative people continue their work, is that I’m hedging my bets. I even say that in the movie. When there’s a function in Jalalabad, and someone wants to give medals to brave police officers or community workers, the police commissioner gets me around to the function because I’m the foreign dignitary. I’m the foreign representative, and I put the medals on their chests and congratulate them. I’m loved in that community by the police, and it’s the same with the Taliban. When Haqqani had his last son, he didn’t know who to celebrate with, so he came around to the Yellow House. We all had nice food, and we all celebrated the birth of his 14th son. He’s got 14 sons. That’s my job.

I can’t really… I want the Yellow House to continue. I can’t really… If Haqqani was a bad person, I’d have to leave… And I didn’t like him, then I’d have to say, “We’ve got to give up this wonderful dream of the Yellow House.” But as I said, the local Taliban led by Haqqani in Jalalabad seem to be okay. We’re lucky, you know? You’ve got to understand. I was in Afghanistan under the Taliban before 9/11. All the negative things that were said about their reign, most of them are not true. Australia had army engineers there clearing land mines, and I went over there to help them with a Mine Awareness campaign.

Yeah, I guess one of the big things that I noticed, or felt at least, was towards the end of Snow Monkey. Even though one of the things throughout that I really picked up on was the strength of community had really come a long way since even the start of Love City, where it was kind of like a fish-out-of-water coming into a community thing. In Snow Monkey, it felt so natural and so together, but then kind of exactly like in Miscreants, when everything is going right, there’s the bombing. Then in Snow Monkey there’s also this bombing a bank, and I feel like those scenes really articulate the kind of horror and tragedy that is still part of all this experience, without centralising it in a way that takes away from the stories you follow.

Well, thank God the only one injured was Bulldog, and he got some glass in his eye, which we got out. The kids were splattered with body parts. The psychological damage to children was terrible. But the thing… People often ask me if it’s hard to come back to Australia. One of my problems is turning on the news. They’ll have a story without even usually pictures saying, “There were two car bomb attacks in Baghdad today. There was a suicide attack in here, blah blah there.” Then if you go to the internet, you’ll find that in these attacks, 154, 160 people, 120 people are killed. Yet when the Lindt Cafe happened, and it was a bad thing, and two people killed, but it was… dominated world news for a few days, and the same with the Charlie [Hebdo] thing in Paris. I think this is leading to a terrible misconception in our society that the only victims of these fundamentalist terrorist groups are the West. In reality, it’s… other Muslims are 100-fold more the victims.

So I think our film shows how… everyone, the boys have just finished their film, and everyone in the city’s happy. There’s… No one in Jalalabad’s particularly religious, you know what I mean? They’re like Australians. You can see that from the film. They don’t get out and pray five times a day. Then suddenly, that happens. There are two reasons why I left all that bloody gore in the film, was… One was to address that thing that it’s not enough to say “there were two car bombings in Baghdad today” and then leave it, but spend a couple of weeks on the Charlie Hebdo thing in Paris. So yes, it’s to try and get people to realise that Muslims are suffering more as a result of this crazy Wahhabist stuff that’s all coming from Saudi Arabia. Shias are not involved at all, for example. It’s all a minority Sunni group.

The other thing is that it’s so important to the story of the boys. They’ve made their own film, they’ve learned to use the cameras, and now… Like Salhudin says, “These people should go to Hell that do this sort of thing.” But he says, “Well, now I’ve realised why I’ve learned to use the camera.” He’s going out every day at 13 years old and shooting stories. He’s not strapping a suicide bomb to his chest, and I think that interview that he… I don’t participate in that interview. It’s reached the point in the movie that by the time we interview the failed suicide bomber, it’s the boys doing the interview, and I think they do a great job.

Yeah. I remember that line where he says, “My brother’s arms are broken and my father’s skull is cracked.” It was just being like… Just completely shaking everything. Then bringing it back, though, with that still kind of perseverance to go on and make these films—

Doing the interview, yeah. And doing the things, yeah, and that’s how it has to be. Like I was reading in today’s paper that in Australia now, a new party’s formed, which is the ASD or something… Some party which is going to go to election on an anti-Islamic platform; that Islam is a dangerous ideology. Islam isn’t an any more dangerous ideology than… If you looked at yesterday’s paper, there was a fundamentalist Jew went and stabbed people at a gay—

Yeah, I saw that.

Yeah. All religions have got that… Christian religion, Muslim religion, Hindu religion… Hindus have gone and killed people. So that’s really bad. What our film shows is that it’s a minority group that are doing this, and they’re probably inspired by intelligence organisations. The suicide bomber explains that the people who kidnapped him whipped him with generator wire, threw him in a pit for two days as only a little boy, and then you saw the other little boys that are training. They’re all ex-Pakistani Special Forces and ISR people. ISR is their version of the CIA. The normal Muslims are the biggest victim of what’s going on in the world today. That’s one of the big messages of our film.

Also, I’m finding that people are terribly misinformed about the Taliban. They find it hard to believe that there’s such a thing as a good Taliban. Yet, it’s so hypocritical. Pakistan, America, Australia, and China are all backing the peace talks between the Taliban and Ashraf Ghani’s people. So what do they want us to believe? Do they want us to think that… “We think there should be alliance between the Taliban, even though the Taliban are bad, evil people and we’ve been fighting them for 15 years”? It’s important to see a film like mine for them to realise that the kind of Taliban people they’re talking to are people like Haqqani who sees… He’s got 14 sons and seven daughters, and he would never agree to the idea of a child being used as a suicide bomber. He’s not being dishonest about that. He is against… he’s saying Afghan Taliban against terrorism. But our news, just like with the thing about not reporting the violence done to fellow Muslims by these minority groups… It’s sort of like you never judge America, because… There’s a movie in this festival about a small company town that has been taken over by the Neo-Nazis…

Neo-Nazis. You wouldn’t judge America on the basis of that one white supremacist group. ISIS is a big Muslim supremacist group, but the rest of the people are just victims.

I think one of the really important parts about this film is how kind of contemporary its relevancy is and how you see all of these really graphic images, but not in a way that’s gratuitous in any way because it’s something that is being shown for a reason, because it’s so kind of under-covered, where you’ve got… Like the mass shooting, as you said, in the Lindt Cafe being covered for days and days and days, and then that getting nothing.

Well, I doubt whether that made it into the news in Australia.

I don’t think it did.

That is… The same people who did the Lindt Cafe did that. Imagine if that happened in Sydney. It’s equivalent to the Bali bombing. It would be huge. So it’s racist, in a way, where we’re covering what these Islamic supremacists, which is what they are, fascists, are doing to us, but not what they’re doing to fellow Muslims. Is it because we see fellow Muslims… In other words, the media generally is creating misconceptions which are very dangerous, I feel. I think that Snow Monkey helps… Everyone who’s been along and talked to me have had their eyes opened to a degree by Snow Monkey and I’m happy with that.

I remember only a few years ago… It wasn’t mentioned on the Australian news that it was Ramadan or Eid. Now just in the last couple of years, they’re mentioning that it’s Eid… Well, they’re as big an event as Christmas to Muslims. The fact that these things aren’t mentioned just has led to general ignorance and misunderstanding. Now, Australians will be… I drove past a place the other day, and I knew it was Eid. I went and bought packets of chocolates and lollies for all my Muslim friends in Sydney. I was driving through Sydney and I saw all balloons up, like over a fence, and thought “oh, that must be for Eid.” Because it was Eid. But most Australians would go past and think it was a birthday party. They wouldn’t realise that today is Eid. Yeah, the level of ignorance is incredible. We’re starting to see a few little breakthroughs, but you know, like at the airport at the moment, I saw the other books, there’s a biography of Saladin. The great Saladin… the General who fought Richard the Lionheart.

Well, I really believe that our schools need to have more inclusion of Persian history. When I went to school, we’d learn about the Greeks and Thermopylae, and how we fought the Persians, but we didn’t learn anything about the Persians. Yet we look at Mesopotamia and what a great culture it was. Babylon. I don’t think the world cared much when Nineveh got destroyed recently, but that would be equivalent to destroying the Acropolis in Greece. If people had knocked down the Acropolis or the Pantheon, the whole world would have been up in arms. But it almost went unnoticed. They’re more concerned about the Buddhas being blown up in Afghanistan. The Buddhas were relatively new. They’re like a thousand years old, whereas… That was the first great civilization.

Was this in Raqqa, was it? Near Syria?

No, that was later. In Mosul, in Baghdad.

Oh, right. Yes.

They destroyed the ancient city of Nineveh, which is the greatest… It’s the one with the winged lions with men’s heads. The great Assyrian art. I’ve been there a few… To me, it was the most important archaeological centre in the world, because it was thousands of years ahead of the Greeks and everyone else. But our ignorance about their culture and that history is incredible. These nutcases within their own culture are now even destroying their own history. A lot of people… this is something that you could be interested in. A lot of people say to me… I was having an email with Michael Ware this morning, you know—

Yeah.

Hardened war journalists like him and Hugh Riminton and many others… I was friends with Hetherington before he was killed. He used to write for Vanity Fair. He used to do photos and stories for Vanity Fair, so we knew each other. All of those guys say to me, “George, you’ve got better access than anyone and yet you’re making a film about ice cream boys in Jalalabad. Why didn’t you do something on the first elections which were on?” Well, I did. Historically, I interviewed all the candidates, but I just don’t make that kind of film. But if anyone wants it, I’ve got the footage. The kind of films that I make are human, and they’re not about news events, they’re about how creativity can be used to solve problems better than war. That’s been consistent through all my work. You know, Soundtrack to War with the soldiers and their music, the Iraqis and their music. Rampage, and the boys with their rap in the ghetto, using that instead of guns. Right back to my first film, Bullets of the Poets, which was Nicaraguan women poets. It’s always been me focusing on the creative in war, and I’m criticised for letting the big stories go. Not covering the big story. That’s not what I do.

I’m not sure if it’s the end of the final cut, but the end with them all on the hills letting the balloons go into the distance… I thought that was the perfect way to end it, in this kind of resounding hope and positivity, in light of it all.

That’s right, well, we’ve got a new cut, not of that, but the end. One of the greatest changes was possible because of this film, in that when we first came to Jalalabad, all of the billboard things were all just shiny metal, because billboards weren’t allowed, because they’d have very aggressive human beings on them, and that was seen as against Sharia law. Gradually, the billboards have come back, and even the Taliban agree with them. When the first ones went up, people threw mud at them. Now you’ll even find billboards which are telling women to come to refuges if they’re getting beaten by their husbands, and others with pictures of men and women. Most recently, there’s one went up where there’s a young lady telling that you don’t have to marry the person you don’t love. That’s huge. Arranged marriages are not law. So that’s a big change.

A young entrepreneur put up an electronic billboard, and his first customers were the Taliban and the religious, and they started immediately using this new technology to put up verses of the Quran and when to come to prayer and when sermons were on. So it became like an instrument of fundamentalism. Being extremely cheeky, I went down and hired time to put our music video up, which is the one you see at the end. So now we’ve cut the end so you’re aware of what’s happening, rather than just being abstract. So immediately, we had some of the nastiest fundamentalists surround us. I had all of the boys there watching the music video, which is like a short version of the film. I let them rant, and then I said, “But here are the children that are in this film. This film was about their future. It could be your children’s future. You know who he is. He probably has played at your weddings. There’s nothing wrong with this video. If you can find something wrong with it, you tell us.” They all pulled their horns in and thought about it a bit, and they said, “Yeah.” So the conclusion was that, “while ever you’re doing that kind of work, we will even take out our guns to defend your right to put it on our billboard.” So that was fantastic.

Now if the Americans wanted to put any kind of American propaganda thing, no matter how worthy it might be, even if it was about sending girls to school, they’d need 100 soldiers with guns and tanks to defend the billboard, and even still, it’d get shot by snipers and destroyed. They would not accept it. But the way we do it is we’re so integrated in the community, it is the community, they can’t deny that. So it gives them a sense of ownership. That even the worst elements in that city now felt ownership of our project. It was a brave thing to do, putting it on the billboard. But it’s absolute transparency. We’re not hiding away in the Yellow House. We’re bringing the product of the Yellow House, and we’re putting it right on the billboard where the Taliban put their own messages up. And I’m going back.

Thanks so much for this interview. It’s been incredible to watch these films building into this in the last few years.

Well, thank you.