There’s something almost sacred about the films of Jean Rollin. Straddling horror, erotica and European arthouse cinema traditions, they emphasise notions—both within the films themselves and through the loyalty of his fans—of ritual, devotion, and dedication. Above all, they are dominated by a cinematic poetry that virtually explodes from a predominantly wordless tension between the sacred and the profane. When it comes to Jean Rollin, the “cult” in “cult film” is no throwaway: Rollin fandom is a religion, a way of seeing at least (to borrow John Berger’s words) if not exactly a way of living.

Making his first film in 1968 with Le viol du vampire (The Rape of the Vampire), Rollin would direct movies almost right up until his death in 2010, capping off his close to 20-strong film career with 2009’s Le masque de la Meduse (The Mask of Medusa). While some films are certainly better known than others, Rollin’s cult reputation as not merely one of the most important French genre film directors of all time but one of the great European art filmmakers full stop stems from extraordinary movies including Fascination (1979), La morte vivante (The Living Dead Girl, 1982) and Le frisson des vampires (The Shiver of the Vampires, 1971).

Edited by Samm Deighn and published by Kier-La Janisse’s film/pop culture micro-publisher Spectacular Optical, the upcoming book Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin is at the time of writing the subject of an Indiegogo campaign to garner funds for its production through presales. The “lost girls” of the title refer not only to the legions of ethereal women who haunt the gothic corridors and desolate beaches of Rollin’s cinema, but to the writers themselves: proudly immersed in the gloriously disorienting and inescapably beautiful world of his cinema, the collection is penned by an all-women team of contributors. Lost Girls thus adds a long overdue perspective to a filmmaker whose work has often been falsely assumed to be of interest almost exclusively to an all-male demographic.

The following roundtable brings a number of these contributors together (myself included) with Deighan to discuss the book itself, Rollin’s broader oeuvre, and their reflections on their own experiences as both women cult film fans and critics.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas: So who the hell are you? Tell us about yourselves!

Samm Deighan: I’m a Philadelphia-based writer, associate editor of Diabolique Magazine, and co-host of the Daughters of Darkness podcast, among other things. And a Jean Rollin fan of just about 20 years now.

Alison Nastasi: I’m one of the editors of the arts and culture website Flavorwire.com, an author, and an installation artist. Over the past eight years, I’ve become known for my writing on a range of horror films, particularly European cult movies and giallo cinema. I contributed to Spectacular Optical’s Satanic Panic book and wrote about Cannibal Holocaust and wendigo mythology for a book director Larry Fessenden oversaw called Sudden Storm.

Kat Ellinger: I am the editor-in-chief for Diabolique Magazine, and co-host of the Daughters of Darkness podcast (with Samm). I also regularly write about film for various other outlets. I am currently working on a couple of books, one for the Devil’s Advocates series on Daughters of Darkness.

Alex: Why Jean Rollin? What lead you to this particular directors work?

Samm: I discovered Rollin through Living Dead Girl, which I bought as a 15 or 16 year old from this bootleg catalogue that introduced me to so many cult and horror films. I really connected with the film because, especially at the time, I was primarily watching Italian genre films (particularly Argento and Fulci) and had never seen anything like it. The way Rollin dealt with sex, violence, and his female characters is so unique, so it drew me to seek out more of his work, even though that was really a challenge for awhile.

Alison: Like Samm, I discovered Rollin at a still young age. Fascination was my introduction. I was transfixed by this vampiric coven of powerful women who used men as objects to be consumed. Rollin’s films had the poetry of Jean Cocteau and the theatrics of the Grand Guignol, which I was obsessed with during that time. I found the film irresistible.

Kat: I found out about Jean Rollin’s work through a series of programmes shown here in the UK in, I think, the late ‘90s (Eurotika, produced by Mondo Macabro’s Pete Tombs). It took a while before I finally got to see any of the films, but the images stuck in my mind as being particularly beautiful. I have always had a fascination with the fantastique, and dark fantasy, which is something Rollin was really good at evoking and so I was absolutely seduced by him before I had even seen a single one of his films. My first Rollin, like Samm’s, was Living Dead Girl. It exceeded all my expectations and took me to a place I had only dreamed of until then.

Alex: I find it really interesting that we all discovered Rollin when we were younger—certainly I am the same (Living Dead Girl on Australian TV station SBS in the 1990s), and while it took me some years to gain full access to his back catalogue, those early images I saw as a teen really clicked something in my brain, and was hugely formative in the development of own cine-aesthetic taste. What other stuff were you discovering during this period, and how did it synchronise with what Rollin offered you then as young women? And what do you get out of Rollin’s films now that you didn’t when you were younger, now you’re a little bit older?

Samm: During those early years (14-17), I was obsessed with generally Italian films—primarily Fulci, but also Argento—and I think Rollin provided an important counterexample to them. Certainly Fulci has some dreamy, surreal, and even nonsensical films, but I don’t think I discovered those more obscure titles till a bit later. Really I think Rollin provided an important segue into my budding love for directors like Walerian Borowczyk and for the more surreal, arthouse films I discovered in college that subsequently took over my life and became (and remain) my primary passion as a fan and a critic.

Alison: In my teens I felt a strong draw toward European genre films, which had a lot to do with my Italian father and also Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs’ incredible book Immoral Tales: European Sex & Horror Movies, 1956-1984. I spotted it in a shop and could not resist the title and outrageous posters. I worked my way through Immoral Tales and tried to watch as many of the movies I could find. It was a profound influence on me.

The Italian and French films in the book were my favorites. Like Rollin’s work, they were visually stunning, provocative, poetic, and philosophical at times. I was already familiar with directors like Argento and Fulci, but I discovered Jess Franco, Joël Séria’s Don’t Deliver Us from Evil, Walerian Borowczyk, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and others. These movies all shared an intoxicating atmosphere and defiant perspective that resonated deeply with me.

What captivates me most about Rollin’s movies now is the outsider artist spirit of his films and his commitment to his personal vision. He was never interested in making mainstream movies and never steered away from his strange imagination and lo-fi aesthetic. The money was never there, but these shortcomings only seemed to fuel him more.

Kat: I have always been drawn towards European cinema and I’m not sure if this is to do with my cultural background, being British. As I was growing up, largely thanks to the BBC and Ch4 in the UK, I was fortunate enough to be exposed to an alternative to Hollywood genre film.

It will probably seem cliche to say, but around the same time I was finding work by other European filmmakers, Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, Jess Franco. This lead me into deeper territory, Zulawski’s Possession (mainly because of the video nasty label on that, an unexpected delight) Mario Bava (who at the time was still relatively unheard of, a fact that sounds crazy now), Jose Larraz and so on and so forth. It started a love affair which has only grown over the years.

Initially what I loved most about these films, especially as a young woman finding my sense of identity, especially in terms of a sexual sense, was the fact that European film didn’t seem to harbour the same puritan morality values as its American counterpart. There was a genuine feeling of liberation to be found, the message you could be sexual AND powerful. Plus, smoking a joint wasn’t going to get you a machete to the head. In addition I also loved the fact that a lot of Eurocult followed dream logic, and allowed you the freedom to develop your imagination, rather than force feeding you the answers.

As I’ve got older my feelings haven’t changed. I just feel incredibly lucky to have spent so many hours with these films over the years. I never grow tired, especially not Rollin. He is one director who rewards me each and every time I revisit his work. There’s always something new to find. He is also a filmmaker who exhibits this sense of freedom I love so much, more so than many of his peers.

Alex: Rollin—alongside Jess Franco—has always felt to me to be a director who has resisted feminist critical models like “the male gaze”: these are unapologetically sexual films that focus on the female body, sure, but there’s something about their almost aggressively dreamlike subjectivity that feels so inherently aligned with the feminine to me. A book on Rollin is one thing, but a book written by all women film critics is quite another. What sparked this idea, Samm? Alison and Kat, as contributors, what are your feelings about being involved in an all-woman collection like this?

Samm: Hilariously, this idea came out of a brief, very spontaneous online discussion of Rollin’s work in general, but specifically on some of the other books on him. Someone suggested to me that I should head the project because of my role at Diabolique and access to a lot of female genre critics/film writers and even though I think it was meant to be a passing suggestion, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Though, to be honest, this is something I could never have imagined myself doing until literally the day of that discussion. My world is almost exclusively male—family, friends, etc.—and it’s really just in the last few years that I seem to suddenly have women in my life. Weirdly, I think as a teenager I tended to gravitate to cult and genre films about women or with a lot of female characters, because it was my way of trying to understand other women, who were and largely still are a mystery to me.

Alison: I’m rather excited to introduce audiences to an oft-overlooked female perspective on Rollin’s stunning films. As a longtime viewer of these movies and a range of genre cinema where womanhood is vital to the film’s appeal, I have always searched for writing by women first. I remember doing exactly that after watching Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People for the first time. Rollin’s appreciation for women and their mystery is extremely evocative.

Kat: It was an honour to be part of this project. I think it is a vital book, and one that offers a much needed feminine perspective on a subject that is often guarded by male critics and fans, and seen as being off limits for us. Yet so many women connect to the work of Jean Rollin, our voice needs to be represented in film criticism surrounding his work. As a female writer, who tends to gravitate toward Euro-cult and exploitation cinema, the female perspective is lacking in the field. It is sorely needed, especially when it comes to reading themes of female sexuality in a positive and personal way, for female fans. I think this book will go a long way towards changing that. I also think Rollin would have heartily approved.

Alex: One of my favourite things about Rollin—again, similar to Franco—is the general ambivalence, often indifference, with which he represents men. I wrote a chapter for Lost Girls on one of his lesser known movies, the rape-revenge film Les démoniaques: there are men in positions of power in this film, sure, but on both sides of the moral equation they are heavily mediated by women who are either more powerful, smarter, or more intuitive. How do you perceive Rollin’s relationship with men in his films?

Samm: It’s surprising, at least to me, the degree to which Rollin doesn’t really engage with male characters. Sure, he has some male protagonists (such as in The Nude Vampire or Lips of Blood), but his worlds are almost exclusively female. When they do appear—and they are peppered throughout most of the films—the male characters often feel relegated to the sidelines: Requiem for a Vampire is a strong example of this. Even though the two “virgins” are meant to be inducted into an undead cult by an aged vampire, he has little to do with the actual action of the film. As far as genre directors go, I think Rollin is one of the few who uses female characters equally as protagonists and antagonists.

Alison: Men in Rollin’s films are always peripheral. His female characters either choose them as partners or exploit them for their needs. In Requiem for a Vampire, the male characters come across as horny buffoons, and the girls use this for their own purposes. You find an element of this in almost every movie. Rollin had an appreciation for women’s intuition, elevating this to a mystical quality in his movies. Outside of that, I’d like to think he realized women are often forced to use a level of that intuition and strategy from an early age to preserve themselves in a male-dominated society.

Kat: It’s almost like men in his films are just there as part of the furniture, with very little power. Of course there are exceptions, like the Grandmaster in La Vampire Nue, but even he is mostly passive. Rollin seemed very critical of men in this respect, showing them up for their violent tendencies, and then mocking them openly for their weakness—be it either sexual or otherwise. I think this is part of what makes him such an important filmmaker in the field of Gothic film. He took narratives, vampires for example, which had been used to support a male dominated environment, with men as powerful, sexual predators, or saviours. Rollin’s world was a mirror image of a pre seventies Hammer Horror universe. A bold move, but a vital one for the era.

Alex: We’ve talked about distinctions between male and female in his films, but for me one of the most striking features of his work is how he utilises landscapes – I guess most famously beaches or bodies of water. To you, how do these more natural environments (or environments more generally) fit into the vision of the world Rollin constructs in his films?

Samm: I think this is what first really drew me to his work. Certainly landscapes are crucial to a lot of horror literature and cinema, particularly anything that could be described as Gothic, but Rollin really makes them his own. He frequently set films in medieval French castles, on his favorite beach at Dieppe, or in cemeteries, and there is something almost revolutionary about the repetitive use of these locations; like the forests and cottages of a lot of fairy tales, you immediately know you’ve been transported somewhere magical.

Alison: I love the fairy tale association Samm made. Rollin described The Iron Rose that way. It makes perfect sense since he was influenced by the stories of his youth, which I mention in my chapter. Just trade the forest for an overgrown cemetery. His otherworldly settings and landscapes are so appealing to me, because they are the Rollin psyche laid bare. The fact that he chooses natural environments speaks to the way he prioritizes the irrational mind and emotions over logical narratives and also gives his work a sense of uncomfortable familiarity. I also read that uncanniness and his fascination with bodies of water, in particular, as another feminine element in his films.

Kat: I adore these aspects, but that’s probably the pagan in me. The way he used rural landscapes, and these buildings that seemed to exist as part of nature and the land (tucked away in the middle of nowhere) or his use of the sea, conjures a true sense of the sublime in a Gothic sense, and a magical sense. His use of cemeteries are just pure Graveyard poetry in living form. So beautiful. I think this all ties into Rollin’s deeper roots which are relatively underexplored, back into Gothic and Decadent era literature, to poetry, to art. To a time where post Enlightenment society was rediscovering their pagan roots and realising just how beautiful nature was.

Alex: Rollin is one of those directors who I’ve always felt really earned the label ‘cult’ in the sense that his fans and admirers have an aspect of the genuinely ‘devout’ to them, it really feels like belonging to a kind of secular, smutty, beautiful religion. This book is very much a solid example how cinema can lead towards the formation not only of fan communities, but professional and even ideological ones: picking up on what you guys have said here, are there other filmmakers in your mind who are urgently needing a similar kind of formal articulation/identification of an appreciative women audience?

Samm: I think for me—and this is a heavily weighted personal bias, as I’ve written extensively about both of them and have been, to a more limited degree, involved with recent Blu-ray releases of their films—Walerian Borowczyk and Andrzej Żuławski. Both are often described as cult directors and they do in depth explorations of female characters and themes like romantic relationships, sex, and love. Like Rollin, their films in general are concerned with notions of personal freedom, particularly as that concept is connected to sexuality. It might be a bit more controversial, but I would also say Alain Robbe-Grillet, and another obvious choice—though he’s arguably more arthouse than strictly “cult”—would be Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Alison: I agree with Borowczyk, Żuławski, Robbe-Grillet, and Fassbinder. I would also add Jess Franco, because of his history with muses and how they contributed to his vision. His films explore female voyeurism, violence, and transgression from an equal protagonist/antagonist point of view like Rollin (as Samm previously stated). I think there’s a lot to dig into about women with the films of Jacques Tourneur, Ken Russell, Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls, Tinto Brass, and Russ Meyer.

Kat: I think I am going to have to agree on Jess Franco, Borowczyk, Żuławski and Robbe-Grillet for the reasons already stated. I would also agree with Alison on Tinto Brass and Russ Meyer. All of these filmmakers portray female sexuality as a source of power. Jose Larraz is another interesting filmmaker, because of the way he portrayed older women who are largely desexualised in most cinema, even in Euro-cult. Larraz made many films in which women in their forties and beyond played interesting sexual roles.

Alex: I would absolutely kill to write essays for the bulk of these suggestions (and would add Abel Ferrara and Radley Metzger into the mix for good luck!). On the subject of ‘dream writing’, more generally, who are your favourite women film critics or film books written by women?

Samm: There are so many, though my tastes admittedly lean towards the academic. Barbara Creed’s Monstrous Feminine and Martine Beugnet’s Cinema and Sensation are both cited in this book (for good reason). Other favorites include Linda Williams, particularly her writings on hardcore pornography (Hardcore: Power, Pleasure, and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible’), Millicent Marcus on Italian cinema (both Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism and Italian Film in the Shadow of the Holocaust), Mira Liehm’s work on The Most Important Art: Eastern European Film After 1945, and so on. Susan Sontag, in general, has been a huge influence on my own writing. And of course Kier-La Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women!

Alison: Barbara Creed and Linda Williams are also favorites. I have read Julia Kristeva’s Black Sun and Powers of Horror many, many times. Maitland McDonagh’s Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds is the Argento bible. Robin R Means Coleman’s Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present should be essential reading for anyone interested in studying horror cinema. Pauline Kael, Kim Morgan, and Karina Longworth, to name a few.

Kat: I love Colette Balmain’s books on Asian cinema because she writes with such authority on a subject that’s so underexplored, really digging into cultural associations and the history. Patricia McCormack’s Cinesexuality was a landmark text for me. She makes dense philosophical theory sound so sexy, and also provides a case to re-evaluate many Euro-cult classics on feminist terms. I need to join in on the Linda Williams lovefest here. Your writing Alexandra, of course. The essays of Angela Carter, who although not specifically a “film writer”, did sometimes write about cinema and shared my love of Eastern European fantasy film (her Sadeian Women book is just beautiful in arguing for a feminist reading of de Sade, and acceptance of pornography as a valid artform). B Ruby Rich’s Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of the Feminist Film Movement contains vital insight into the women’s film movement. I also love A Skin for Dancing in: Possession, Witchcraft and Voodoo in Film by Tanya Krzywinska.

Alex: For you, who is Rollin’s most important or intriguing woman character?

Samm: This is nearly impossible for me to answer, but I think I’m going to have to go back to Living Dead Girl’s Catherine. I love the way he interprets monstrous characters throughout the second half of his career—such as the bevy of female monsters in Two Orphan Vampires—but Catherine really embodies a lot of his themes. She’s completely innocent, because she first has no memory beyond her childhood, but is a strange vampire-zombie hybrid. She is still able to feel love and, later, regret, making her one of his most tragic characters, and she exudes an agonizing sort of loneliness that I think is part of what makes the film so powerful.

Alison: It’s incredibly tough to choose, but it probably goes back to Brigitte Lahaie’s Eva in Fascination for me. She’s an icon of Rollin cinema and everything he loved about women. She lends a powerful physical presence to every scene she’s in. Her expressive performance style helps Rollin straddle the line between dream and reality that makes his work so intriguing. And her popularity as an adult film actress during the ‘70s introduced new audiences to his work.

Kat: This is a mean question (laughs). I almost don’t want to answer because no matter what I say, I will no doubt want to come back and change it five minutes later. Ok, intriguing…Isolde, from Le Frisson des Vampires because she has this mystical association with goddesses and occult magic. Hmmm but then so does the Vampire Queen from Le Viol du Vampire. And don’t get me started on Fascination’s Eva…

Alex: To finish up, then, for those yet to be indoctrinated to the Church of Jean Rollin, where would you suggest they begin and why?

Samm: Probably Shiver of the Vampires, because it’s a solid example of his early, surreal vampire films, which everyone seems to associate him with. I’d also say Living Dead Girl, because it’s one of his most accessible (and was my personal first), and Fascination, because it’s so iconic and unusual, while still being a horror film.

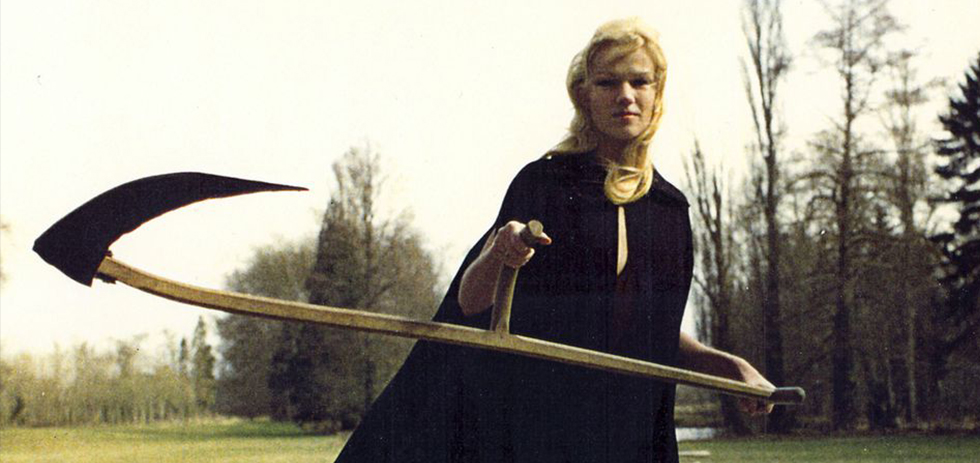

Alison: Fascination would be a great place to start. It feels like the most accessible Rollin film in the vampire series. There’s a hypnotic quality carried over from his early works, but the story and performances are far more naturalistic. Rollin’s muse Brigitte Lahaie makes a sexy grim reaper, giving us one of the most iconic images from European horror cinema.

Kat: I am going to have to agree with Samm and Alison and go with Living Dead Girl and Fascination. Both films are great primers, contain all his main themes, but are slightly more accessible than his, shall we say, more surreal works.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas (@suspirialex) is a Melbourne-based writer, an editor of Senses of Cinema, a regular contributor at 4:3, and the 2017 AFIRC Research Fellow. Her books on film include recent monographs on Ms. 45 and Suspiria.

Samm Deighan (@sammdeighan) is a Philadelphia-based writer, an associate editor of Diabolique Magazine, and a co-host of the Daughters of Darkness podcast.

Alison Nastasi (@alistasi) is a Los Angeles-based author, an editor at Flavorwire, and an installation artist. She writes on a range of horror films, with a focus on European cult movies and giallo cinema. She contributed to Spectacular Optical’s Satanic Panic book and wrote about Cannibal Holocaust and wendigo mythology in the Larry Fessenden-edited book, Sudden Storm.

Kat Ellinger (@moonmin_stiggy) is a Philadelphia-based writer, the editor-in-chief for Diabolique Magazine, and a co-host of the Daughters of Darkness podcast. She is currently working on several books, one for the Devil’s Advocates Daughters of Darkness series.

For more information on LOST GIRLS: THE PHANTASMAGORICAL CINEMA OF JEAN ROLLIN, the Indiegogo campaign is online here.