What does a historical site mean to us after the events that marked the annals of time have taken place? What signification does it take on as a product of this passage of time? This has been an exceptionally tense political question over the years, but it is a tension that is equally produced by questions of a philosophical and temporal nature. Almost by necessity, meaning comes after the fact — it is a synthesis that is born of looking back — and the entire discipline of history has grappled with how best to make meaning out of what the past leaves us.

The question becomes all the more pointed when what the past has left us is not a letter or a photograph but a place, one that people will return to and put to use. We continually layer new functions upon sites that have borne witness to history, functions that land traditionally somewhere along a spectrum that runs from commerce to commemoration. But each of these new functions — even the construction of the comparatively noble memorial — implies this same process of abstraction from the historical moment that is its raison d’être. Though it may guard the traces of the historical event that birthed it, the memorial shifts the historical site into the realm of historiography, into the telling of its own history. We might say then that a historical site has meaning only to the extent that we have extracted it from history.

Quietly recording the procession of tourists through the Sachenhausen and Dachau concentration-camps-turned-memorials, Sergei Loznitsa’s Austerlitz speak to these issues of place, time and commemoration in the typically restrained manner that the director has shown in his documentary films over the years.1 Across the film’s 90-minute runtime, visitors to the two memorials from around the world file across the screen, moving through the camps and the litany of atrocities that mark each individual section.

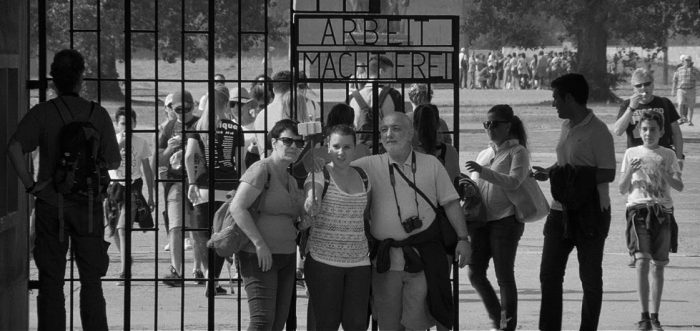

In documenting this collective movement, Loznitsa’s film offers up almost a catalogue of actions that we have come to associate with the international discipline of tourism: photography (of oneself and of others), wandering about with a mixture of uncertainty and a desire to feel more at home, the impromptu social microcosm of the tour guide and tour group. That these touristic gestures often clash harshly with the backdrop against which they take place seems undeniable but is also perhaps inevitable — what would we rather these people do? What would satisfy our yearning for the historically appropriate response? To my mind, Austerlitz is as much a criticism of the uneasy alliance between tourism and history as it is a document of the most recent iteration of an especially historically loaded site. Loznitsa captures the co-existing layers of past and present that define the remnants of the Sachenhausen and Dachau camps at their respective memorials, playing off the sites’ present socialised tourism against the physical, material structures that root them in history.

Loznitsa’s concern for depicting the co-existing temporalities of Dachau and Sachenhausen is first and foremost expressed stylistically, particularly in the director’s handling of the space and architecture of the memorials. While the film’s static camera setups, long takes, low-contrast black-and-white images, and eschewing of voice-over commentary has earned Austerlitz the (somewhat unhelpful) “austere” tag in reviews of the film thus far2, Loznitsa’s depiction of the camps resembles something closer to a mathematical logic.3 When establishing a point of view of the camp, the director sets up his frame to reflect a building’s geometric harmony or the graphic qualities of a corridor: his compositions continually favour the description of space over the people in it.

Loznitsa also seems to position his camera at just the right distance from the groups of tourists to make any moments of individual identification and human narrative development seem fleeting. Sonically, this calculation of distance seems to follow the same principle: we only ever hear snatches of conversation or expository tour guide monologues, the overlapping sounds of voices creating a precarious international aural stew. Loznitsa’s decision to keep his distance and to populate his frame with crowds makes the film’s handful of shots showing just one person in them all the more striking. Even then, the director keeps his distance, opting to keep his subjects in long shot and dwarfing them against their surroundings.

That Loznitsa tends to show the human activity of groups rather than individuals at these sites speaks also in a sense to the sociological undercurrent that runs through Austerlitz. The crowds of people that move through the director’s static frames constitute a kind of counter narrative to the architectural history, a document of the behaviour of people in the ambiguous site that is the holocaust memorial. Here, tourist photography becomes a particular point of interest. We cringe at the sight of tourists pretending to pose behind bars at the entrance gate bearing the Nazi camp slogan Arbeit macht frei (“Work sets you free”), and again when a middle-aged man imitates the hanging of political prisoners for a photo snapped by his partner. The feeling engendered by Loznitsa’s aloof vantage point is hard to shake, if not especially productive: we feel as if they simply haven’t understood or acted with the self-effacing solemnity that the situation demands. But what does Loznitsa contribute to this economy of righteousness in the face of past injustice? More than just a rejoinder to this behaviour, Austerlitz is a stark depiction of how human organisation finds its old banalities in these repurposed historical spaces.

Perhaps Loznitsa’s restrained sobriety won’t be to the tastes of viewers who desire a slightly more forceful directorial voice in their filmmaking. Yet it is precisely the director’s economy and calm before this loaded historical subject that makes Austerlitz all the more powerful, allowing the vagaries of past and present to unfurl fugue-like in counterpoint before our eyes. It is a worthy addition to a body of work that has continued to trace the contours of loss, memory and history.