Queensland Film Festival and the Institute of Modern Art (IMA), in Queensland’s Fortitude Valley, have partnered to screen a series of experimental film programs in 2017. The IMA, an independent arts centre established in the mid-1970s, was a venue for the inaugural Queensland Film Festival in 2015.

All three of the announced programs are concerned with landscapes, whether physical, digital or mental. The first program strand, Sheltering Islands, screened in February this year. The second, Speleogenesis, screened 29th April. The final program, The Unity of All Things, screens on June 3rd.

In this feature piece, Jeremy Elphick writes on the films featured in the final screening program, Could See a Puma and The Unity of All Things.

Could See a Puma, 17 minutes, 2011

Eduardo Williams can be a relatively difficult filmmaker to write about, considering the passionate reactions his work is frequently able to provoke. When I walked out of Williams’ debut feature The Human Surge at 1:30am in at last year’s Locarno Film Festival, accompanying me was roughly half, if not a third, of the audience that walked in. There were some of us who were enamoured with the film, and others who hated it. The latter were convinced it was their ardent duty to preach the film’s failures: it didn’t make sense, it was offensive, the camerawork was shaky. Up to a point, it’s arguable that Williams’ first feature could be a frustrating watch for those unfamiliar with his short film work, or the broader cinematic style that his films fit within. The Human Surge emerged as a culmination of a series of stunning experimental shorts that Williams’ has released over roughly half-a-decade, the earliest of which came in 2011, his short Could See a Puma.

In the run of four short films in the lead-up to The Human Surge—Could See a Puma, The Sound of Stars Dazes Me in 2012, That I’m Falling? in 2013, and I Forgot! in 2014—Williams operated within a cinematic universe very much his own. A scene of waves crashing up against the face of a cliff, until slowly, in the background of the shot, a person walks into the scene and asks “Do you know where I can find a cybercafe?”. A group of teenagers in Vietnam on a parkour adventure, before the handheld camera that has been shooting them suddenly lifts off into the atmosphere. Williams relishes scenarios like these, inherently surreal in content, but constantly tied, neatly, to the most common actions. These moments sprout and punctuate intentionally prosaic narratives; the images they map together providing the most lingering impressions within his work.

When Eduardo Williams released Could See a Puma a little over half a decade ago, it operated as a distinctly imaginative observational film. One of the most arresting aspects of Williams’ work is the way he captures and interprets the environments that encircle his characters. There are four locations in Could See a Puma, each bleeding into the next. The short opens with a group of friends, as they walk across a series of Argentinian rooftops that tesselate into one another, until they settle on one and begin to lay down.

From here, the short begins to drift into a subtle supernatural space. “Wanna play out of credit?” one of the boys asks. The other responds with a clear “No”. He continues: “Please I’m out of…” before suddenly collapsing. They all laugh. After this, a quick change of brightness twists the scene into something strikingly different.

“There are traumas from your past from which you can’t recover.”

“Yes”.

“You prefer to spend time alone.”

“Yes.”

“Can’t sleep due to bad thoughts”

“Yes.”

The questions continue, spiralling on and on until another one of them falls over – this time, we fall down too.

We emerge in a universe of mud, ruined buildings, and a marsh. Williams films the scene in a series of long takes, capitalising on the particulars of the space: the natural light of dawn or dusk, dominant pink hues, an expansive depth-of-frame littered with fragmented pieces of concrete, nothing living bar the subjects in sight. There’s few overt indications that this world isn’t in reality, but something feels distinctly unreal in the way Williams ties it all together. The dialogue winds on as the boys move through the landscape:

“How old are you?”

“13.7 gigayears”

“And me?”

“13.7 gigayears”.

Eventually we’re in a swamp, the same scarce light flickers off the dark water, muted by a handful of evidently deciduous trees. As one of the boys asks whether the air pressure has changed, it marks another specific shift in the film; we are now in a dark forest on a windy night. We remain here until the film ends in a collapse into itself.

Eduardo Williams was 24 when Could See a Puma was released, and there is astounding sense of depth in the work. It’s a film that becomes more impressive in when seen through a contemporary context, as a clear signposting of how Williams views and approaches cinema. Watching a scene or a thought from one of his short films reemerge in a later work is thrilling in a certain way. There’s a sense of artistic transparency at play, where Williams’ is taking concepts and ideas we’ve seen at their genesis and bringing them into new, complex landscapes: away from indirect absurdism and towards something more pointed and lasting.

The Unity of All Things 物之合, 98 minutes, 2013

While I am familiar with Eduardo Williams’ work, I hadn’t seen anything from the directors of the feature film his short was paired with. Alexander Carver and Daniel Schmidt’s The Unity of All Things has a lot in common with Williams’ work though: both films are shot overwhelmingly with 16mm film, with Carver and Schmidt also dipping into 8mm at certain points. With both films produced on low budgets, there’s a lot in the choice of using a format of celluloid over digital. It’s a more expensive format to shoot on, there’s a process to having the film development, and it lacks the ease of shooting digital when it comes to cutting each take since the format is substantially more finite.

In Could See a Puma, the celluloid dictates the length of the film’s long takes, giving the work a sense of only slightly distorted reality that consistently throws off the audience. That’s an approach more at home in the slow cinema genre in The Unity of All Things: careful framing, scarce use of handheld shots (opting instead for tripods, jettisoning any unnecessary panning), and prolonged still shots with the subjects on screen serving as the catalyst for the transformations in the images over time.

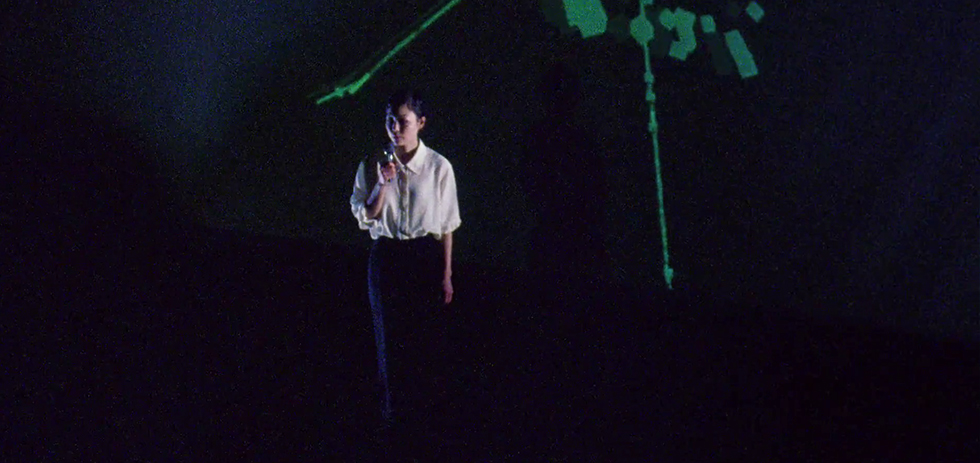

Carver and Schmidt’s film is an experimental take on the sci-fi genre, deconstructing the form and typical tenets of such films before reconfiguring them into something more abstract and hallucinatory. Fittingly, there’s an overwhelming emphasis on technology, with the opening scene centered around an object called the International Linear Collider – an obvious riff on the Large Hadron Collider of our universe:

“Why don’t I belong here? How do I find my place at the new collider?”

“You don’t have imagination or vision. I do like you. I don’t know where you belong. You lack all ambition and I am full of passionate intensity.”

There’s an eerie, calculated nature to the dialogue, something also prevalent throughout Could See a Puma. It feels intentionally robotic, every phrase is measured carefully; less concerned with realistically mirroring how we talk, the directors instead work on cleanly severing the work from certain realms of reality. It builds and feeds into an atmosphere often difficult to define: is it right to feel paranoid? Is this a form of communication to yearn or fear?

“The tone of your voice shifted. It was felt in the audience.”

“I became distracted. I was thinking of our recent paper on accelerator-based global communications systems. I was overwhelmed. Though, it is funny to share such radical thoughts with an audience of anonymous men. Men who are entirely unmoved by the implication that these thoughts may have for the society in which they live. Without a unified leadership within our community about the polyvalent, applied-design, potential of acceptable science, I see no reason to build something as big as the ILC.”

“I love when you talk that way, but you must broaden your focus.”

There’s a loneliness that flows through all of the shots, a disconnection that feels almost impenetrable at times. In one scene, a woman watches old 8mm shot from a Gondola going up Tianmen Mountain, reflecting on her youth with a pointed nostalgia. This is the future now, she is surrounded by technology, and she is reminiscing on this old footage, cut into the film in a way that clearly capitalises on its 8mm format.

Chunky old ViewSonic monitors are positioned against these new technological developments in the Collider, framing the film with a certain internal dissonance: it’s advanced in so many ways, yet in others, gargantuan pieces of technology dominate. It’s a collision of sorts, with these little head nods to how the future was viewed in the 20th century, against reality of advancements we live with today. This is our world, where particle accelerators are steering electrons, shaping research and progress. This world shot through 16mm, with CRT monitors as a status quo.

The locations of the film—like Williams’ aforementioned debut feature (which jumps between Argentina, Mozambique, and the Phillipines)—are spread out, as an almost thematic necessity: both filmmakers hone the strength of their critiques, their images, and their ideas around technology and globalisation through the ease of movement between place and context. The seamlessness with which this is achieved distinguishes them from a dearth of filmmakers who attempt the same thing.

There is a scene at dawn or dusk on a beach in The Unity of All Things that is reminiscent of the opening shot of another Eduardo Williams short, I Forgot!. Figures float in the ocean, as waves crash over and cover them. They eventually reemerge, with next to no reaction. These are the most sublime images of the work, terrifying, and beautiful in a way that is hard to pinpoint. The jarring cuts back and forth between these scenes and shots of computer hardware and factories makes it more pronounced. In its title, The Unity of All Things says a lot about how it operates as a film: it weaves these fragmented images and scenes into one another, creating a work that is captivating in the cohesion it achieves without compromising on the scope of its vision. It’s a smart pick to screen alongside Could See a Puma, as both works push against the limits of the mediums they operate within.