Late in Warwick Thornton’s We Don’t Need A Map, Professor Ghassan Hage of the University of Melbourne is talking about stolen land. It’s to be expected in a documentary addressing white Australia’s entrenched ignorance of indigenous issues, ideas and history but Hage isn’t making a point about ignorance, rather one centred on a knowledge that runs to the heart of Australian colonialist identity. Fear of boats and refugees mask a collective psychological panic: our land will be taken from us. “You know it can be stolen,” Hage says direct to camera. “Because you did it.” Half an hour earlier, the academic explains the merits of the catch-all epithet “fuckwit”. That’s the kind of film this is.

Commissioned by NITV as part of their ‘Moment in History’ initiative, the playfully slapdash documentary is ostensibly about the iconography of the Southern Cross; the very making of the film was prompted by a national controversy Thornton stirred in 2010 when he suggested that the constellation was becoming akin to an Australian swastika. “I’m starting to see that star system symbol being used as a very racist nationalistic emblem,” the director told the AAP, a statement seen as abhorrent despite coming a mere half-decade after a series of anti-Muslim race riots in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire that brought to the fore the racism simmering beneath the veneer of popular nationalism.1

When Thornton focuses on the Cronulla Riots in one of the film’s many digressions, audio plays from John Howard’s infamous post-Riots press conference. “I do not accept there is underlying racism in this country,” the Prime Minister said. It’s a memorable soundbite, distancing the persecuted Muslim community and the furious — and furiously paranoid — great white horde from the rest of the population. In We Don’t Need A Map, advertising executive Dee Madigan speaks to this kind of sloganeering political deflection: ‘Stop the Boats’ is good, ‘Children Overboard’ is bad. Remove references to people, focus on ideas and objects. That’s as much political spin as it is Australian history: until 1967, the indigenous population of this country were considered flora and fauna.

This emphasis on soundbites is at the core of Thornton’s subtly woven thesis.2 Indigenous history and the history of white Australia run on perpendicular lines, but the disconnect isn’t merely substantive. The indigenous Australian history Thornton explores — in Yirrkala, Katherine and Alice Springs — is united by form: oral storytelling. We hear of songlines that lasted a week and mapped out the land of neighbouring nations, beautifully impassioned odes to Djulpan (as the Southern Cross is known to the Yolngu people) and stories of Dreaming passed down from grandparent to grandchild. In contrast, the history of white Australia is one of co-option and carefully selective denial, a sputtering remembrance of past guided by the then-contemporary political climate.3 It’s an issue of scope. Writer Bruce Pascoe reflects on millennia of Australian history and reaches a salient point: all we ever talk about is “sheep and a lost war.”

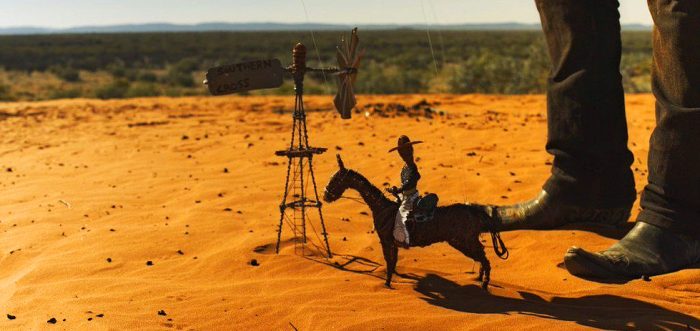

This reductive view is well within Thornton’s sights when his film is at its most irreverent: every 10 minutes or so, he plays puppeteer with figurines made of copper wire, acting out an idiosyncratic Australian history (a sign reading “Fuck Off, We’re Full” features twice in the pre-1967 era, for instance).4 These sequences — at first daggy, then quite funny — work to puncture any overt self-seriousness, as does the amusing tactic of filming both interviewee and interviewer. Many a time we watch Thornton — camera on his shoulder and camera assistant Drew English adjusting the focus — work to get the best possible shot. At points the Aboriginal custodians interviewed openly note the artifice of the film; Rev Dr Djiniyini Gondarra of the Golumala clan pauses his story about a cultural meaning of the Southern Cross so Thornton can get the framing just right.

Levity is an easy takeaway in a documentary that manages to address a broad range of pressing contemporary discussions on race, history and identity. Thornton’s scattershot approach enables this; though the film feels long for its 90-odd minutes, it’s never dull or prescriptive. This seeming lack of forcefulness may offer superficial comfort to a white liberal audience, but as the laughs subside, what remains is a sharp prompt for self-assessment: you are “inheritors of theft” — of land, ideas and symbols — and you have so very little to show for it.