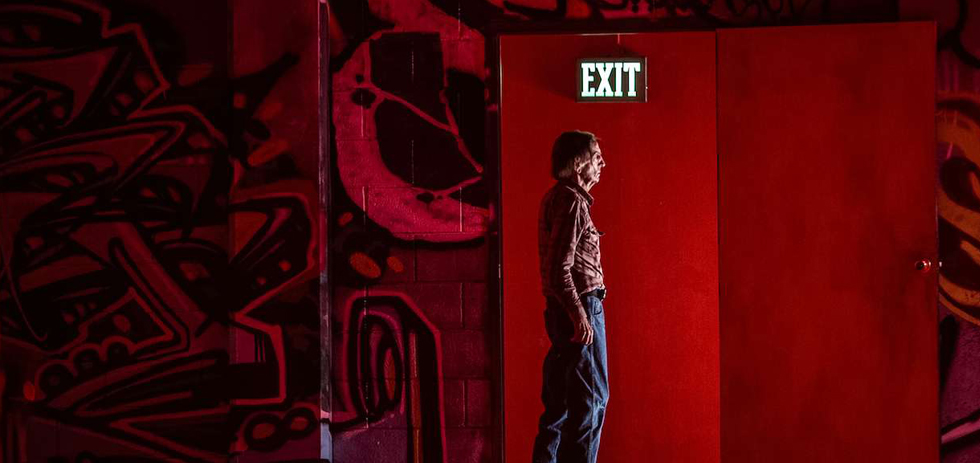

Midway through September this year, Harry Dean Stanton passed away at age 91, a little less than six months after his final feature film — John Carroll Lynch’s Lucky — had its world premiere at SXSW. Functioning as a swan song for Stanton, Lynch’s debut feature film draws on notable hallmarks of the late actor’s filmography; Lucky is punctuated by winding, dialogue-driven bar scenes, and the bar itself is in a romanticised desert town in America’s South West. For such a small film — one shot in merely 18 days — Lucky boasts an impressive cast and crew, who took on the project because of their own affinities for Stanton. This universal affection for the actor shines through in the most intimate moments of the films, when the scenes drift towards reality.

At Locarno Film Festival, we spoke to John Carroll Lynch about working with Stanton in Lucky, and the challenges of making a film about mortality so closely anchored to reality. Our conversation took place a month before Stanton passed away.

Note: This interview was conducted as part of a roundtable discussion with several other film journalist. For the sake of transparency, all questions asked by the other participating journalists are preceded by an asterisk.

You’ve been an actor for decades but this is your directorial debut. Do your experience as an actor has been helpful, now that you’re stepping into a position where you’re directing other performers?

John Carroll Lynch: I’ve watched for my entire career directors approach actors, and watched what was successful and what failed. What helps really great directors work with actors and what makes for the opportunity for failure? There were a lot of things that I observed and thought, ‘Those would be really helpful skills.’ And also as an actor, to be directed, there were times where I’d think to myself, ‘You’re taking the wrong approach.’

Actors are asked to adapt a lot in the work. That’s part of what you sign up for, part of what you want to do, is to adapt. And directors, I thought for a long time and it’s only recently come to my understanding that directors didn’t have to do that because they’re working on their own material. But after working on this with the actors that I got to work with — let’s describe them as mid-career professionals — you realise that you have to adapt a lot to say the things that they need to hear, not what you would need to hear as an actor. Because their approach is going to be different than yours, and that was particularly true of Harry Dean, because Harry Dean doesn’t accept that he’s acting at all.

That’s a primary tenant of his work: “I don’t act.” And that’s a really interesting place to be, because it’s like if you’re not acting, I guess I’m not directing. And yet I do have to direct you, so how exactly are we gonna come to that? And we came to it. It was a really fascinating thing, and it was exponentially made more interesting and difficult by the personal nature of the material, because the material is like exposing the brick and concrete of his life. So it was really vulnerable and really personal work for him, and it was taking pieces of his life, stories that he’s told, thoughts that he’s had, and rearranging them and attaching them to a totally different person. It’s absolutely crucial for the way in which he works to not be acting, to not be anybody else. So it was really fascinating. After a while I began to go, “Wow this is gonna be really tricky.” And it was really fun.

He worked on the story with the writers?

Yes, what happened was the writers wanted to write something for him from his work, from his life. There’s a documentary of him called Partly Fiction, and it’s so much of his life in the movie. He did serve in World War II, he did serve on a landing ship tank, he was attacked by kamikazes, he did shoot a mockingbird. It was his life, those stories are his.

When I got involved as the director we started talking about, “Well these speeches, these scenes, we need to tie them into a construct, we need to tie them into a story that the audience is going to follow from beginning to end.” We didn’t want it to be a story where many of the things that happen in movies about age and about living at this time in your life happen — where you’re gonna go back and you’re gonna say you’re sorry to old lovers or you’re gonna try to somehow make it right.

I liked the fact that we weren’t gonna make it about making it right. We were gonna figure out how does a guy look at himself, as somebody who’s dying at this moment in time, and still live fully? And do that without any safety net, without any God, with no second act? his is it. And I love that. I mean I loved that about the drama of the movie. So it was tying Harry Dean’s personal world and personal relationships into that construct. That was the work of it with he and I during the process of making the movie.

*How is he?

I mean he’s incredibly fragile and tenacious at the same time. He’s lucky, that way. That vitality, that sense of hanging on, that sense of “I’m not leaving” is still a part of who he is, at the same time that the door’s narrowing as it is for all of us. It’s just we somehow seem to accept it as being more present when you’re 91, which of course it is, you know? Because the numbers, the odds are against you. But one of the things I loved about it was it’s just a matter of distance. It’s really what everybody’s… when I get up in the morning, I don’t know what’s gonna happen. If I’m really facing it, right? If I’m really gonna face it and make my life fully true and real, if I’m gonna face the realism of it, I’ve gotta live today like I’m on penalty time. I don’t know when the ref’s gonna call it.

I remember that line “realism is a thing” and how it goes on to frame the narrative the film navigates. Towards the end, there’s this particular blend of what’s real and what’s performed; the actors seem at their most sincere and convincing when it feels like they barely need to perform — where,for instance, it could just be a scene of David Lynch talking to Harry Dean, rather than the characters they play. I think that was most pronounced when the film was most emotional, in those final scenes.

Harry Dean’s character is coming to the realisation of how he’s gonna do it right? Like he’s come to the realisation of how he’s gonna face that empty — face the desert in some ways, without having to make up something that he can’t believe in. He’s not gonna make up what he thinks is a fairy tale to make it okay, and he’s telling people that. He’s talking about what he thinks, that the truth matters. And the truth is that there is nobody out there, that we’re spinning; there’s a line in Partly Fiction where he says: “Did you ever think about the fact that we’re moving around the sun at 17,500 miles per hour right now? You ever think about that? Doesn’t that scare you that we’re actually going 17,500 miles an hour right now? And we can’t feel it, and how fast is the spiral arm of the Milky Way going while that’s happening? It’s like we’re on a huge massive celestial octopus at an amusement park and we can’t feel the movement of it. The little car is spinning but we’re just sitting there like ants in the car thinking what we’re doing actually matters.”

That’s how he thinks about it, so he’s getting people who are at one level or another willing or unwilling to actually go to that place, and Beth’s character is the one who’s most rooted in the need — she owns her space. She’s fighting for it in that scene, and that’s why she became so emotional because he wins the argument. He wins. And she’s got to face that thing, but he gives her what he thinks the answer is.

I’m interested in how that translated to actually shooting the scenes with the parallels to his own life. Was it quite an emotional shooting experience?

There were many times where it was very emotional and difficult for him, and where he resisted. He resisted for many reasons, many of which were absolutely right because you’re acting a piece of material — even if it was fiction you would have sensibilities and perceptions and you’d be bringing yourself to the role. An example is I was talking to him about Bertila Damas’ character — the bodega owner whose name is Bibi in the script — and the writers took the name Bibi from Harry’s longtime housekeeper Bibi. He loves Bibi, you know, they’ve been together a long time, so when we were shooting those scenes I kept on going to him, and he’s a guy who’s 100% certain he’s not acting, so it’s like “This is not your Bibi, this is a different Bibi,” and he’s like “No man, it’s gotta be my Bibi. It’s gotta be mine.” And he was adamant about it, and I was like, “Okay I’m gonna have to back up and create something else,” because he does not accept imaginary circumstances. This actor will not accept imaginary circumstances.

Okay, okay, then I’ve gotta figure out a different way to approach him, because that’s my job. My responsibility was Lucky. So we found ways to find the moments that we needed, that the story needed, that were with that incredible truthfulness that he never abandons. Which is the reason why every single person came to the set — to work with that guy, and to work with that artist who just will not lie.

What’s the experience of working with him as an actor?

It’s wonderful and frustrating and delightful and angering. He challenges you. He wants to be directed, and he does take direction, but you have to earn it. He’s gonna make you earn it, and I don’t mind that one bit. Because it’s come to my understanding that in the heat of it, for some actors, that can be where the magic happens. And he has to be both feet in and has to be real and he will not accept anything but that. That was what I wanted, that was what everybody wanted, and that was why everybody wanted to write the story and make the movie because we wanted that truth. And that’s how he makes it, so okay, let’s make it your way. Essentially that’s what it was: Fine we’ll make it your way, because it’s your life. We need you. So that was part of what I went after, and what my job was.

*I think that’s one of the most effective parts of the film, that he’s reconciling with himself, not necessarily reconciling with some external kind of truth; it’s all within himself. And it’s all okay for it to be sort of intangible as well.

Yeah, I like the fact that you say he’s reconciling with himself. It is intangible because it’s an intangible thing. The beauty of how he works and who he is and what he brings is that an audience can experience that intangible thing as concretely as a brick to the head. He somehow makes you be with him and you’re there, and that was what we wanted to create was that journey of being with him, being with Lucky.

*It’s not usual that we see David Lynch acting. How was it for him?

I’ve experienced him as the actor he would come to set as every day. He prepared himself in the way he would want actors to prepare themselves, and he made the choices he would want actors to make. And then he’d come to the set and be willing to take direction the way actors he’d like to work with would take direction. We had conversations that he needed to have because there were things that weren’t clear —and in some ways I was trying to be the director that I’ve always wanted to work with, and have worked with, to encapsulate those virtues and the work ethic of the directors I have had the good fortune to work with. He has a lot more experience obviously as an actor than I do as a director, so he has a few more hacks at the plate than I do in terms of the new relationship to the material — but he was everything one would hope to be in an actor and more, because he’s also intuitively aware of the frame line, of the cut points, of the focus. He was just fantastic. He comes in and you see him and you know, that’s David Lynch. Then when he’s asked, “Howard what’s the problem?” and responds “President Roosevelt’s gone”, you’re in his dilemma, and then you just completely forget it’s him. I completely forget it’s him. And I think it’s a tribute to collaborate on the work. He did a great job, and he came for Harry. He came for Harry Dean. If Harry Dean were to do something else and Harry Dean asked him to I think he’d do it again. I have no doubt. Because he just loves him.

*The gay couple at the bar, and obviously the owner of the bar is a woman. Did these elements come from Dean’s own character? Would you consider him to be a bigot in that sense?

No, I’ll tell you a couple stories about that I just love. But first and foremost Lucky, the construct of Lucky is a man in his time right? I really wanted to have a scene… I was like I love this Liberace speech but I need to have some context for it. I said, “What if we have a scene where we have these three young people sitting in his seat so he couldn’t sit in that seat, and then you think you understand that the woman and the man are together, and then the man kisses the man. That way you see he was a person who, he’d get frustrated but you wouldn’t necessarily know whether he was mad at the fact that they were — and Harry Dean was great about it.

The writers were really reluctant for a while, but I wanted to set that speech up about Liberace, I wanted the audience to have that sense of a guy who might be homophobic in their mind when they began that, and to get to that end thing about like, “I wonder why I was even worried about that. What was I even thinking about? What difference does it make?” I wanted them to be thinking about it, in that intuitive sense, I wanted it to be laid in just a little bit.

Anyway, we were working on the material and he goes, “I don’t understand, why am I mad at these two guys kissing again?” And I was saying, “Well this is what I’m trying to set up,” and Logan says to him — longtime assistant, 20 years they’ve known each other — he’s like, “Uh yeah um, you know Harry you’ve never felt this way but people of that generation, a lot of people were homophobic,” and he goes: “What are you talking about? Of course I felt that way. I was in the Navy in World War II, of course I felt that way. We used to beat those guys up. Of course we did. But then I got to think to myself what the hell am I worried about?” And he said basically the same thing, “What difference does it make to me? Let them fuck whoever they want to fuck. Good for them,” that’s basically what he said.

He kind of talked himself into the thing, the correct position. So we get to the day and we’re talking about exactly the right level of frustration, where he came to that beautiful realisation. Because for me it just reads, “Oh this again. This too? They’re sitting in my seat and this?” and it’s a comical moment. We need one after what he’s been through. After the setting up of the story we need some more humour, so it’s funny the audience laughs. So after we’re done with the scene, we go “Okay Harry thanks, you can go home.” He got up and he walked over to all the actors and he gave the woman a hug and gave both guys kisses on the lips, and said, “Bye you guys.” It was fantastic. And Mikey, one of the guys in that scene, was the on-set dresser, and he came from Richmond, Virginia because someone asked him to come and told him it was a Harry Dean Stanton movie. He slept on her couch to work with Harry Dean Stanton. So from David Lynch to Mikey, everybody came through.