Playing in the French Competition of the Cinéma du réel documentary film festival in Paris, director Julien Faraut’s L’Empire de la perfection [In the Realm of Perfection] is a dazzling lesson in montage, tennis and what it means to capture the real. An audiovisual archivist at INSEP [l’Institut National de Sport, Expertise et Performance, France’s national training centre for elite athletes], Faraut has cut a singular path for himself over the last 15 years making films that mine the institute’s collection of footage, exploring the intersections of sport and cinema. L’Empire de la perfection is Faraut’s second feature after 2013’s Regard neuf sur Olympia 52, a striking excavation of sorts of Chris Marker’s practically unseen and unheard of debut documentary on the 1952 Helsinki Olympics Games. If, as Faraut admits, he owes a certain debt to Marker’s protean imprint on the history of filmmaking in the last 50 years, it translates into a sensitivity and willingness to question images, a desire to go deeper into their possible meanings and itineraries across time that marked the latter’s body of work.

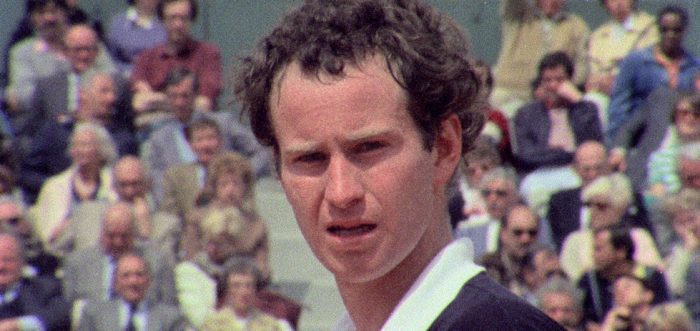

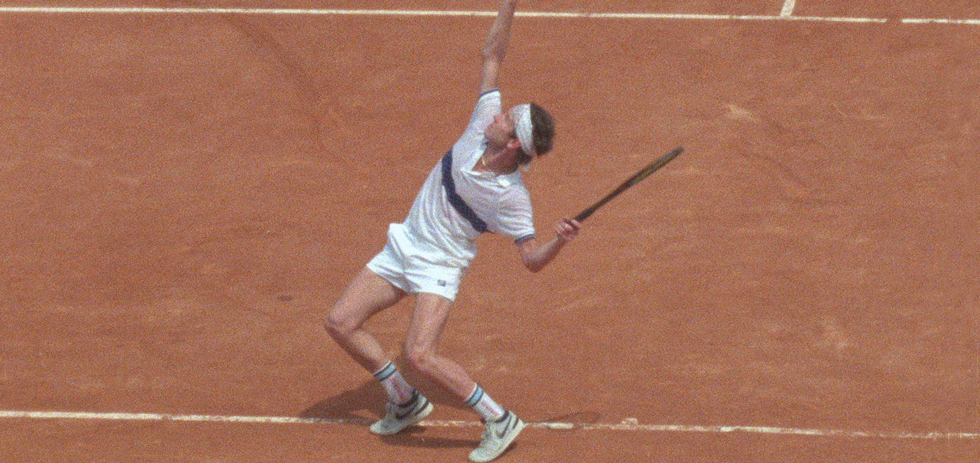

L’Empire de la perfection sees Faraut draw upon a rather unique wellspring of footage: that is, excerpts and 16mm rushes from pedagogical tennis films directed by the late Gil de Kermadec, France’s first ever National Director of Tennis. After first seizing upon the possibilities of improving the standard of French tennis via the medium of pedagogical filmmaking in the mid-1960s, de Kermadec began filming “technical portraits” of the great tennis players of the day a decade later, setting up impromptu film crews at the Grand Slams to record and analyse what made these players great. Here, Faraut hones in on de Kermadec’s vast collection of footage of the ex-enfant terrible of American tennis, John McEnroe, recorded at various French Opens in the late 1970s and 1980s. While infamous for his on-court outbursts and often antagonistic relationship with the arbiters of the game, McEnroe was also a consummate technician and possessed an impeccable understanding of the dynamics and geometry of the tennis court. De Kermadec’s footage captures the best player in the world fending off not just his adversaries, but the personal obstacles that stand between him and attaining perfection.

While extracting something of interest from what were essentially instructional films for aspiring tennis professionals may seem like a tall order, Faraut succeeds by dint of his sharp, rhythmic approach to editing and an ability to pull together ideas and images through discursive intellectual movements. Passages analysing the mathematical precision of McEnroe’s shot-making sit comfortably side-by-side with references to Daney and Godard; detours into the philosophy of the classic cinéma-vérité/direct cinema split rub shoulders with observations on the tactics of clay court tennis. What results is one of the more remarkable films on sport I’ve seen, and also a model object of archival filmmaking in a terrain that is in danger of being sunk by the worrying confluence of quantity and unambitious mediocrity.

I spoke to Julien in the foyer of the Centre Pompidou in between screenings, where the film has been well received by French audiences after premiering at the Berlin International Film Festival last month. We covered questions of cinema and television, film and video, and the pitfalls and joys of the archive. And of course tennis, that most noble inheritance of the fallen French aristocracy.

Note: this interview was originally conducted in French and has been translated by the author.

After Friday night’s screening, you spoke a little about the genesis of your film, L’Empire de la perfection, and its links with your job as an audio-visual archivist at INSEP. Could you tell us a little about the origins of the film?

Of course. As I sometimes say at these screenings, this project had a certain originality in terms of its conception as an “archival film.” The usual hierarchy [of work with the archive] was somewhat disrupted. Usually, the archive is first and foremost illustrative. Often in reports made for television, archival images exist as a kind of visual wallpaper, with this omnipresent voiceover telling us what we need to know. The archive is thus generally manipulated and exists in servitude to a pre-written narration. When one works on a historical, social or political subject, generally one works with what has been written about the subject; these so-called “archival” images are just reheated, so to speak, and served up with this existing historiography that comes from the written word. Also, often when one decides to make an archival film, it’s because one has a desire to work on a particular subject for which you go to the archive to find the images to illustrate your ideas.

But this happened in reverse for your film.

In reverse, yes. The images almost came to me.

So you found them by chance?

That’s right. So, my day job as you say is at INSEP’s film archive. INSEP is a public organisation funded by France’s Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sport, whose principal goal is to train elite athletes. It’s a training model that is unique to France, I believe.

So, in your department at INSEP, films are made for the purposes of training athletes that are then archived for future use?

That’s right. So the institute’s film archive was founded around the start of the 1960s.

Right around the time Gil de Kermadec started working for them.

Yes, exactly. It first collected some of the existing sport films produced before the institute’s creation, like [Chris Marker’s first film,] Olympia 52. Next, the institute turned to the production of their own films, including those co-produced with the French Tennis Federation that were directed by Gil de Kermadec.

De Kermadec was appointed in 1963 as the first National Technical Director of the Tennis Federation. At the time, this was a totally new position in France. He was in charge of the development of the technical aspects of the sport that were to be taught and then practiced by trainers and players all throughout France – I’m not sure if there is an analogue in Australian sport in this period.

And so these instructional films date back to that period?

Yes, that’s right. De Kermadec takes up the position in 1963, and his first film comes out in 1966: Les bases techniques du tennis.

Which we see a clip from in your film…

Yeah, right at the beginning. So, upon taking up this new position, de Kermadec envisages two big projects. The first is to organise a tour of Australia for France’s top tennis player. As you know, Australia was at the top of the tennis world in the 1960s: all the best players were Australian, and French tennis was far from the lofty peaks it had reached in the 1930s. So, Gil said to himself, “Right, we’re going to Australia, we’re going to rub shoulders with the best of the best, and we’re going to see how they train.” And so off they went.

Around this same time, he decides that his other pet project would be to start making instructional films in order to analyse the fundamentals of the game and to thus improve the technique of French tennis. So in 1966, there’s the first film. Gil has an office at the Institut National de Sport [which later becomes INSEP]. There he has all of the technical equipment, cameras, and all of the camera operators who work for the national sporting federation.

So these were shot by professional camera operators?

Well I mean they didn’t work for the film industry, but they had a good level of training. They were trained to film sport, which is to say they knew 16mm technology well and, above all, they had made some forward strides in high-speed camera technology, which allowed them to record in super slow motion. So there was a degree of technical expertise there.

Moving back to the production of my film: in 2011, a colleague of mine, Nicolas Thibault, was making a film about Gil de Kermadec. At the time, Gil was nearing the end of his life and was quite sick. He was suffering from Alzheimer’s, and he needed concrete things to jog his memory. Nicolas asked me to take Gil to the INSEP film archives, which you see us doing in my film. So I found myself in this place – this “cemetery of forgotten films” as I call it – and it was there that I found my new treasures: the rushes for Gil’s instructional films.

Gil’s working methods were very particular, which made the process of sorting through these canisters of 16mm rushes particularly difficult. In making his films, he was not at all interested in the matches themselves that he had filmed. What interested him was the players, the way they hit the ball, their topspin, volleys, slices, returns of serve, and so on.

So his aim was to capture the actions of individual players, not a match between two opponents.

Exactly, it was to capture these actions as they appeared over the course of a match. So over time, he accumulated these images of players, starting in 1977 and finishing in 1985, which became these sorts of individual technical portraits, if you will. As McEnroe’s portrait was the final one he completed, McEnroe was the player for whom he had accumulated the greatest quantity of rushes. There were literally kilometres of rushes: 25 canisters filled with 600 metres of film.

What’s interesting is that these rushes are almost always destroyed. The film laboratories preserve the photochemical elements with a view to striking a print. At the end of the editing process, when the director has come up with a final edit, the lab makes a master cut and working copy, but the rushes are destroyed. But, for whatever reason, we had these ones. So, what followed was a long process of cleaning up the films and exploring them bit-by-bit. What was particularly arduous was the fact that I had this accumulation of very brief shots that I had to physically tape together with scotch in order to make a sequence. The other problem was finding the sounds that matched with these images. As you can imagine, there isn’t a huge amount of difference between the sound of a backhand and forehand…

Right, I can imagine…

But slowly, I began to explore the images and started piecing them together. The film was born almost surreptitiously. Each time I discovered a new batch of images, I had the impression that these common thematic elements were beginning to emerge. So I started to group them together. I waited to see what the rushes had to say. The first great revelation came after stitching a sequence of images together for the first time – without even knowing if I was following the continuity of the match, I might add. But it was the fact of creating a sequence of images of tennis out of 16mm footage: that is, to see this filter that created a prismatic view of an event that I already knew. I was too young to have seen McEnroe play in person in 1984, but I’d seen a lot of the images of him playing that were broadcast for television.

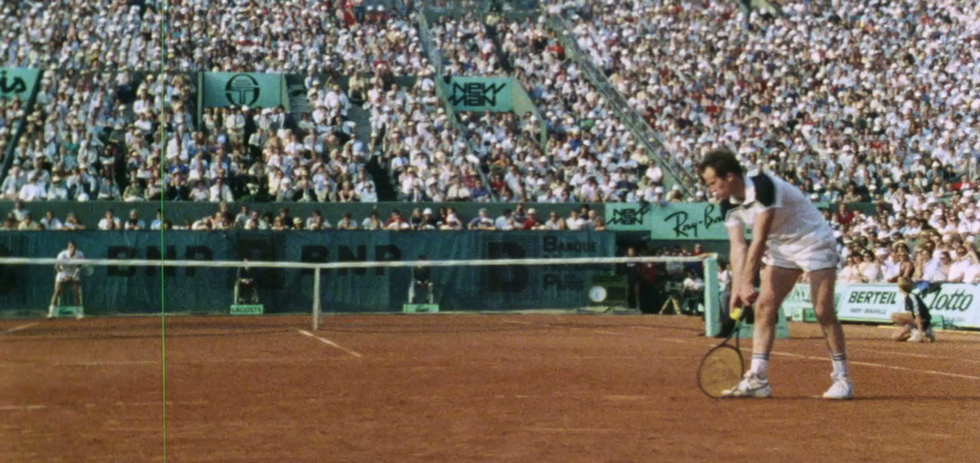

The 1980s was the period when video technology takes over for television, and it is very rare to see tennis from the mid-80s shot on 16mm film. So, the first revelation was the strangeness and ambiguity of these images: the physical support recalled the cinema, not a televised broadcast of a match. That created this ambiguity, which was, “What am I watching here? Is it a film about McEnroe? Wait no, it’s a real match at Roland Garros!” That gave me a number of directions to pursue in the film. Right then, I knew I wanted my film to be shown in cinemas; I didn’t want to make a film for television with interviews etc. I later found out that Gil had really fought to film the matches in 16mm. The French Tennis Federation wanted him to just use the footage of the match from the television broadcast, but Gil wouldn’t have it.

But de Kermadec’s films remained within the sphere of institutional, instructional cinema, that is, they still had a largely pedagogical function?

That’s right, they were for players, but there was a certain level of ambition there… With the 16mm cameras, what really interested Gil was to devise his own shooting positions, putting him in control of the angles that he would later piece together and study. For example, he created these bunkers at the back of the court from which to shoot the match, which don’t exist at any of the other Grand Slams. Those bunkers really angered McEnroe, who was totally against them.

They were a distraction to him while he was playing.

That’s right. You have to understand the proximity of these cameras – they were even closer than the guy sitting just over there [Faraut gestures to someone sitting about 5 metres from us]. And the cameras would make a good deal of noise too, you’d hear this [imitates sound of film camera recording noisily].

But from the bunkers, you could see the subtle rotations and bounces of the ball exceptionally well, the topspin, the slice etc. From the side of the court you miss that.

So that’s why he wanted to put himself down there. But we also see in your film the other cameras he had positioned around the court.

Yes that’s right. There was another cameraman shooting at a three quarter angle from the sidelines. He would ignore the match but focus intently on the movement of the player’s feet.

And the third?

The third would sit up in the stands, giving us a more general view that resembled what you would see on TV. He was on tactics: the length that the player hit the ball, how they made their opponent move, how long they would wait before hitting the ball to the other side of the court.

So, Gil wanted his cameras. And he also really wanted to be able to film in slow motion, something that you couldn’t do as well for television. With the 16mm camera, you could film at 400 images per second, which would allow you to play back the images in very slow motion when you projected them [at 24 frames per second].

So, there were certain things that Gil wanted that television couldn’t give him. You watch a broadcast of a game to see a match, so that’s what they’ll show you. Gil instead wanted to make technical portraits of players, slowly accumulating them performing every type of shot over the years. He wanted us to understand the players, the choices they made, their bodies, in order to understand the tennis that they could then produce.

It’s funny, and we see this a little in my film, Gil started from an idea that you can teach people to play tennis a certain way, that there is a method that everyone can learn and eventually master. But when you watch the champions of the sport play, there are no two that play the same way! So he changed tack. Instead of saying “Ok, now turn this way, move your feet like that,” he said, “Here’s how the great players do it. Take your pick!”

And me, as an aspiring athlete, I would say “I’m more Lendl than McEnroe”…

Right, right. He understood that it was up to people to develop their own technique. Are you Navratilova or Hana Mandlíková? And so on.

Going back to Gil’s footage, I was also really struck by its strangeness. I’ve been watching tennis on TV since I was a kid. In a television broadcast of a match, there’s an aesthetic that exists there, a rhetoric of images if you like, that goes from the position of the camera to the little close ups on the players’ faces at the end of points. With your film, we have a totally different way of watching the sport. Not just with the physical support of 16mm film, but also the moments that we are privy to and the manner in which we see them.

Right, that was the other big revelation for me after the 16mm: the fact that I was face-to-face with these rushes. The rushes are all the images that we have during a production; the start and end of sequences that aren’t edited into the final cut that subsequently end up on the cutting floor. As it’s very rare to see these rushes, even for me in my work, I was really surprised to see how much you could see going on in these off-cuts. What we see is not just a document of the object that is being filmed, but a document of the filming itself, because we see the crew discreetly communicating and signalling for the start and end of takes. This created a kind of permanent double reading [une lecture double permanente] of the images that is also made possible by the small size of the tennis court. When McEnroe takes a seat in the break in between games, he ends up in the same line of sight as the sound recordist sitting a few metres back.

Right, it’s not like a game of football or cricket where you have to set up those drone cameras to capture what’s going on.

And the thing is, the sound recordist, even in a documentary where the process of filming itself is normally scrubbed from the final product, is usually out of shot. But there, all of a sudden, something which belongs to the off-frame world is in frame. At a certain point in the film, I started to show McEnroe and the sound recordist in the same shot – I loved seeing them together. It gave an added richness to the footage: it took on the appearance of a “making of” that was paradoxically constituted by the images of the film itself.

The film and its construction alternate.

Right. I also began to notice that the relationship between McEnroe and the cameramen was often exceptionally tense – I didn’t realise that he had lashed out at them physically, for example. So this, then, became a subject in my film.

Yes, there is a turning point where you start looking at how McEnroe would act in front of the camera.

Yes, this becomes a thematic interest of my film. Because we see that Gil changed what he was doing after the early instructional films of the 1960s: now, instead of imitating the gestures, he is capturing reality, that is to say he is capturing players performing these gestures during the match. If Gil needed footage of the player hitting a smash to complete his portrait, and the player never hit one, the crew would sit there for two hours without filming a metre of film! So, now things are happening that are out of his control.

But in following this line of thought, that led me to another problem that I wanted to confront in the film. I wanted to take up this question of a cinema of the real [cinéma du réel] but to think about it in terms of a reciprocity between camera and subject. This is to say, it is difficult to film the real, because we don’t control the real. But conversely, the real is affected by the presence of the camera. In the film, McEnroe starts to get angry because he feels the sound of the camera is encroaching upon his space. Even physically, at one point he shows that their proximity is bothering him as well. So I found it interesting to bring that into the film.

I find that the documentary film is more dishonest than fiction, because it rarely speaks to the manner in which it deforms the reality it films. The example I give to students or to young people who are starting to get interested in documentary film is Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922). We explain to them that the igloo was constructed for the film…

…and the outmoded method of hunting Flaherty had Nanook perform.

Exactly. I feel like we’re still there in 2018. You see a lot of documentaries where the camera’s presence is totally effaced, and people leave the cinema saying to themselves “I felt like I was there, in that war, like I lived through it.” It’s never said, but there was someone there behind the camera, who made the choice about the angle to shoot from, someone who also makes editing choices. All that disappears from the project with the film. What I found fascinating in the rushes was that one couldn’t get rid of the film crew’s presence because they were physically in the frame. So I stopped cutting them out. It truly fascinated me.

In making what people sometimes call a “compilation film” or an “archival film”, that is, a film based on images shot by other people, the question of manipulation is perhaps even more pointed. The question becomes about imposing (or not imposing) a meaning or a reading of these images that isn’t there.

I think I manipulate quite a lot. I play around with the images at my disposal. From a viewer’s perspective, these “archival films” can be very regimented. You know my previous work, I feel a lot closer to A Grin Without a Cat (Chris Marker, 1977) than, say, the T.V. series Apocalypse (Isabelle Clarke, Daniel Costelle, 2014) on WWI. I think we can be playful – I don’t think you have to be too respectful either. It can be amusing to make use of images, or to put to them to re-use [de pouvoir exploiter, réemployer]. I owe a great debt towards Marker, especially with this notion of the re-use of images that runs through all of my work.

That’s what we see with Marker and a few others that crop up around that period: we have this impression that we are seeing a re-use of images. They are not there to be stuck to words, but rather to be understood again. Yet it’s not quite a question of détournement in the Situationist tradition either…

Sure. Sometimes, though, I practice that kind of détournement, like when I interrupt the film using the image of the woman holding up the clapperboard. But yes, a détournement ought to be funny, or ought to give rhythm to the editing, but it should also be there for a reason. And in that sequence with the recycled clapperboard lady, there really was a stop in the flow of the match! McEnroe stopped playing, he insisted that the court was unplayable, that there was too much bounce, so he sat there and wouldn’t play. The cameramen stop filming, the spectators don’t see the match, so I wanted to stop my film too.

I’m really at home when it comes to editing, and I take a lot of pleasure in it. The benefit of working at INSEP is that, as I’m often occupied with tending to the archives or teaching, my projects often develop over long periods of time. While I stop working on the editing, the film is left there to mature like wine. I’ve been making films for 15 years now, and I’ve learnt the importance of periodically abandoning the editing process and then taking it back up again. You come back feeling fresh, feeling like working again, and solutions begin to appear to you. It was particularly arduous work, going through all those reels, and the work with the material itself took an exceptionally long time. L’Empire de la perfection took three years to make, and several months to edit. But at the heart of it, as you say, it’s an archival montage – in the noble sense of term!

I don’t have any experience in making these kinds of films, but I imagine that a potential frustration might be that you want the image to say something that ultimately just isn’t there. Sure, you can manipulate it through editing and say, “look here, he’s hitting the ball up the line, then there’s a backhand” and you invent an imaginary point. But you seem to have wanted to avoid doing that. Is there also a level of frustration that exists in working with other peoples’ images?

Of course there is a level of frustration. Sometimes you want to find the images that you are missing, that you would like to have. But on the other hand, when you find an image – whether you were expecting it or not – this can create a great feeling of satisfaction and joy. Like when I found the footage of McEnroe approaching the bunker saying “Piece of crap! Get out of there!” – it’s extraordinary! He looks straight down the lens of the camera and it feels like he’s coming right for us. Those types of things are real finds… I found a couple of shots right at the end that I just adored, like when McEnroe plays with a cardboard cutout of himself [during a photo shoot]… So I don’t find everything that I want, but I also find things that I hadn’t at all expected to find. There’s a certain joy in letting things happen, in accepting that the images are what they are.

So the pleasure comes in the lack of control?

Absolutely. It’s also a learning experience in terms of teaching yourself to understand and appreciate things as they are – because in the end, you don’t have everything.

It seems to me that there is a whole tradition of directors who follow this philosophy when it comes to archival images. You get this feeling that they want to exploit this very chance-like aspect of their having found them, and to see what these images have to say rather than imposing themselves on them. That’s what I liked most about your film, in the end.

To change tack a little, I wanted to ask you about the excerpts from Serge Daney’s texts that appear in the film. Were they familiar to you before you started the film or were they something you sought out during the production?

Well as I’ve been working at INSEP for 15 years, and having worked a lot on the subject of sport and cinema, [his texts] seemed to be an obvious reference point to reach for. I knew some of his writing, but had never fully immersed myself in it before the film. As a starting point, I wanted to pose the question: what was the editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinéma doing [at Roland Garros]?1 Why is he writing about tennis?

In reading his articles on tennis, which were collected in a book entitled L’Amateur de tennis (POL, 1994), the thing that immediately attracted me to them was the sharpness and pertinence of his thinking on the sport. Same with Godard, for that matter. Daney could sometimes be a bit of a provocateur, taking aim at intellectuals and such, but that’s not at all why he was there. He wasn’t there as an intellectual who was covering something as mundane as “the tennis” to seem younger or cooler or something – because that happens here in France. You get intellectuals, people who come from the world of culture, who are invited to write about the Rugby World Cup or whatever, and it’s all very superficial. But Daney, he really had a sharp mind when it came to tennis – just like he did when it came to cinema – that revealed a great sensitivity to the technique and strategy of the sport.

The thing that surprised me the most was that he had managed to find the common denominator between tennis and cinema, which was the question of duration. He talks about this a fair amount, but it almost never gets brought up when people mention his tennis writing. Why do people love tennis? Because, contrary to football or rugby, a match isn’t 90 minutes long or two 40-minute halves in the case of rugby. It can be anywhere from 21 minutes to 11 hours and 30 minutes, if we take the two extremes in the history of the sport. You can be down two-sets-to-love and come back to win a match two hours later. When we ask ourselves, what is it really that constitutes the specificity of tennis, it’s the fact that the players create the time of the match – they subtract from it or keep adding to it.

There’s a quotation of Daney’s that we didn’t manage to put into the French version of the film but that will appear in the English version. It’s really a beautiful, colourful way of defining McEnroe’s game. He says, “Borg places the ball in the spot his opponent has just left. McEnroe places it where his opponent will never get to.”2 And it’s true. When you watch McEnroe play, he hits these angles that no one else could hit. No other player had the same trajectories as him, and his opponents would be played off the court. I didn’t put this in the film, but I think that it’s probably for that reason that he was poorly judged by the lines people: the balls are following these improbable trajectories.

Maybe that’s why he was always getting angry!

Well, you see it in my film, the French umpires and lines people [at Roland Garros] weren’t professionals: they weren’t trained for the elite level of the sport. The thing is, when you watch closely, in the majority if not the totality of cases, McEnroe is right about the line calls!

Anyway, that was something of a digression, but in any case, I wanted to show that I wasn’t just including Daney for Daney’s sake. His writing about duration in tennis was a philosophy he had of the sport, but which found its most fitting manifestation in McEnroe’s game. McEnroe was an attacker, he decided when the point was over. Even with the return of serve, he would hold up his opponent until he was ready to go. He’s controlling the clock [il a les manettes du temps]; there was a technical domination at play, but there was also a temporal and spatial domination there.

At the end of the film, you finish on a reconstruction of sorts of the 1984 Roland Garros final between Borg and McEnroe. We spoke earlier about how Gil de Kermadec worked, and how his instructional films focused on the gestures of the players and not at all on the recording of a match between opponents. Could you elaborate on the process of making that final sequence?

Well, in tennis, the first thing that comes to mind is the dramaturgy of the sport that is so unique, the way a match can completely change shape in a matter of moments. In a best-of-5-set grand slam match, it’s almost like a Greek tragedy in 5 acts. That element of drama was absent from my film up until that point; I was lacking its essential element, the dramaturgic – and, by extension – cinematic element of tennis. So it was necessary to turn towards narration.

Gil didn’t film the 1984 final in continuity. As per usual, he regularly called cut, often for quite obscure and seemingly trivial reasons. For example, a cloud would pass by overhead, and so he would stop shooting because at that moment, he wanted to shoot a slow motion sequence for which he needed a certain amount of light. Or, at other moments he felt that the player was going through a bad patch and wasn’t about to produce the tennis he was looking for, so he wouldn’t shoot. Often he was looking for shots he hadn’t been able to capture. So he would film in a very fractured, stop-start fashion. For a long time I wasn’t sure whether I’d be able to tell the story of the final. Would I have the images to do it?

As if something were missing from the story.

Right, something that would allow me to recreate this dramaturgy. There was a narrative that already existed of course, which made things complicated. In the first two sets of the 1984 final, McEnroe is ultra-dominant. But if I happened to find a point from those first two sets where Lendl had the upper hand – because he managed to scrape a few points together, all the same! – then that wouldn’t work within the narrative of the match.

That posed an interesting problem for me. There are, ostensibly, two ways to watch the sport of tennis. One, you buy a ticket and go watch the match in person in the stadium, which to me is the best way to do it. The second, the most common, is to watch the match at home on the television, where we watch a selective, edited broadcast of the match. But I was choosing a third way, which was making people go to the cinema to watch a match. Wouldn’t I then have to invent a third way to watch the sport?

The other problem was that I had to tell the story of an event of which most people knew the outcome. Well not all, I suppose there are people that don’t know who won in ’84…

I didn’t know! I’m too young…

Well, there you go. But many do! And so I said to myself, I’ve just got these bits and pieces, so it almost corresponds to a spotty memory of the event. Memory comes through in patches, it doesn’t run continuously, we have images, flashes that come to us. We remember a point – so I thought about it as a remembering of the match.

Then I said to myself, if there is something that differentiates a television broadcast from the cinema, it’s once more the question of time. Cinema is first and foremost the art of the ellipse: we sometimes see the story of an entire life told in 90 minutes. Yet it feels continuous. A rugby match on television, you see two 40-minute halves, there are some ads, but you don’t miss anything. And so when I thought about the fragments of footage that I had, it was no longer a frustration.

You were obliged to work that way, in a sense.

Right, exactly. And then I noticed that the television broadcast was totally occupied by the result, the score, the numbers. It’s the same thing for every sport. When you watch them on television, there’s the time that winds down in one corner, with the score next to it. For me, [with the footage I had,] that wasn’t at all the case. At the beginning instead I had trouble situating each moment as corresponding to this or that point.

So you had to go back to the television broadcast…

Right, exactly. But I told myself, “OK, I don’t have the score stuck to the image, so I’m going to hone in on the dramaturgy of the images themselves.” On their cinematic qualities, if you will. The dramaturgy of a match and the score of course aren’t always in sync. Say you’re playing a game of football. Your team hits the post three times, but your defender scores an own goal, and the ref gives an absurd penalty. You lose 2-0. The people that didn’t see the match will say, “2-0! Pretty clear winner.” The people watching will say, “You should have won 3-0!” It seems obvious but it bears repeating.

In watching this footage, you notice that each point is its own little story, and you watch – without context – to try and figure out who has the upper hand. In the film, you see McEnroe lose his footing, a shot that I repeated three times. I felt there that the tide had swung irresistibly in Lendl’s favour and there was no stopping him. This was my way of fashioning this cinematographic version of tennis.

Based more on duration than the score.

Yes, and also on little moments. With the music as well, I wanted to work with the emotions of the players and what they were feeling.

Right, because the ending of your film is truly tragic. I remember leaving the cinema with a real feeling of sadness. I mean, sure, McEnroe was a professional tennis player who won millions playing the sport, he’s probably going to be fine. But you get the impression that that loss at Roland Garros in ’84 really hurt him.

It was totally traumatic for him. As a competitor, he had few equals in the sport, and he was one of the greatest players of all time. But he never won Roland Garros, and thus never entered into the pantheon of players who completed the grand slam, all because of that match. In 1984, he lost two matches. Two. He played 104. He lost one right at the start of the season, and then the Roland Garros final. And nobody thought Lendl had a chance of coming back to win that match! It was a disaster, and it remains so to this day for him, for this perfectionist who was in the end unable to attain perfection. That’s why I wanted to put that record [of 104 wins and 2 losses in a calendar year] up at the end of the film, to show what the cost of perfection is.

For me, the film is also a portrait of elite sport in general. When you see elite athletes, you are often struck by the ease with which they perform, the fluidity of their movements. But we forget what that takes. In my work, I see their training, I see the sacrifice, the harshness of their everyday training. I think it’s important to talk about elite sport in those terms, in terms of the incredibly high psychological stakes.

Absolutely. Let’s leave it there. Thank you, Julien.

Thank you, pleasure.