Written by Conor Bateman and Jeremy Elphick, with additional writing from Jessica Ellicott.

A year ago this week, we took aim at Sydney Film Festival’s full program announcement for its safe choices for higher-profile screening slots, as well a pronounced lack of East Asian films. This year, not only have these issues been mostly addressed, the programming as a whole seems to have embraced the (relative) unknown: the most high-profile filmmaker screening this year is likely Spike Lee, whose last theatrical release in Australia was Inside Man in 2006.1

The line-up presented by festival director Nashen Moodley this morning seems focused on a future generation of directors. Only two directors in the Official Competition have made more than three feature films, and a noticeable trend across the program this year is debut films from ‘non-directors’: journalists, artists, assistant directors and producers of SFF films from years gone by, as well as directorial turns from actors (in shorts alone we spied Spear’s Hunter Page-Lochard and Lion’s Dev Patel).

For much of it, audiences will have to rely on some handy filmic connections to navigate the program; noticing Toni Erdmann star Sandra Hüller in rom-com In the Aisles, or the festival’s banking on residual love for Ildikó Enyedi’s 2017 Official Competition winner On Body and Soul to bring crowds to Zsófia Szilágyi’s One Day (which, also in competition, could land Hungary the first-ever back-to-back crown). The latter film, a domestic drama played as a “jigsaw puzzle” thriller (which makes it sound like a nightmarish version of Ramon Zürcher’s The Strange Little Cat), is a fairly good indicator of this year’s competition line-up as a whole: a measured move back towards the stated criteria of “audacious” and “cutting edge,” at the expense of big name directors.

In keeping with Szilágyi’s film, the competition is focused on stories told at the margins, narratives often glossed over, and accepted histories and truths that call for some sort of reconsideration. Milko Lazarov’s Ága sets itself in the snowy wilderness of Sakha, a Russian republic at the country’s northmost tip, where an Inuit couple struggle with the intersection between tradition and modernity, while Annemarie Jacir’s Wajib meditates on the conflict between two generations of Palestinians through the turbulent relationship between a father and son. The Heiresses, from Paraguayan director Marcelo Martinessi, takes on class and sexuality head on, telling the story of turmoil in a decades-long relationship between women in two wealthy families.

Kamila Andini’s The Seen and Unseen is one of several sophomore efforts in the competition, with the Indonesian filmmaker exploring states of childhood grief and mortality. Laura Bispuri’s Daughter of Mine is presented as a follow-up to 2015’s Sworn Virgin, which set between Albania and Italy — explored Balkan tradition and history, though its inclusion in the competition implies the film will work as a standalone piece. In the competition’s only standalone Australian inclusion, Jirga, a former Australian soldier returning to Afghanistan in search of penance puts his life in the hands of a village justice system — the Jirga. The festival is touting the real-life stakes in the making of the film, which apparently had funding rejected due to ‘political sensitivities,’ right as preparations for shooting had begun in Pakistan.

The most represented country in the official competition, taking up three of twelve slots, is the United States, with two Sundance premieres — Leave No Trace, from Winter’s Bone director Debra Granik, and Desiree Akhavan’s gay conversion comedy The Miseducation of Cameron Post — and, as previously mentioned, the latest from Spike Lee, BlackKkKlansman, a Cannes-bound thriller which follows an African-American cop (John David Washington) who infiltrates the KKK in 1970s Colorado with the help of a white colleague (Adam Driver). It seems set to be Lee’s take on the Blaxploitation genre and perhaps a rebuke to the freewheeling race rhetoric of Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight.2

Perhaps the most left-field competition choice is Matangi/Maya/M.I.A, a art documentary focused on the titular pop star. Its competition berth implies a provocative approach to the music bio doc, less lavish reenactment like the Nick Cave love letter 20,000 Days on Earth and more a feat of editing: the film was cut from footage in M.I.A.’s personal archive.

For our money, though, the most alluring competition title comes from the ever-reliable Berlin School filmmaker Christian Petzold. Transit, a thorny ethical drama set in Nazi-occupied France, seems to be a companion piece to 2014’s brilliant Phoenix; where the latter channelled Hitchcock’s Vertigo, this new feature seems enamoured with his The Wrong Man. It’s worth pointing out, too, that this will be Petzold’s first film written solo; since 1995, his feature screenplays have been collaborative works involving the late great filmmaker Harun Farocki.

Last year we felt that the Special Presentations section of the festival squandered some potential in its selection. The State Theatre is a tricky venue, though; it’s the biggest at the festival — requiring decent ticket sales — but it’s also the most unique and compelling screening experience on offer each year. The Official Competition sometimes manages to marry both concerns, as in the singular experience of watching Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights in 2015, but Special Presentations are, for the most part, focused on filling seats.

Once more there are clearly targeted demographics — daytime subscribers are going to pack out the 14 June screening of The Wife, for instance — and a trio of perhaps unnecessary American inclusions — the indifferently-received new Gus Van Sant (Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far On Foot), a Maggie Gyllenhaal-starring remake of Nadiv Lapid’s The Kindergarten Teacher, and an adaptation of Nick Hornby’s limp novel Juliet, Naked. But there are also films like Lynne Ramsay’s deeply disturbing You Were Never Really Here, which sees Joaquin Phoenix play an Iraq War vet who rescues young girls from sex trafficking rings, and Gustav Möller’s gripping thriller The Guilty, which took home audience awards at Rotterdam and Sundance. We’re also pleased to see a handful of films from the teaser announcement — Foxtrot, The Insult, West of Sunshine and American Animals — screening as part of the State Theatre selection.

There’s a strong presence of Cannes films in the Special Presentations series too, with the latest from Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, 3 Faces, and a new anime feature from Summer Wars director Mamoru Hosada, Mirai. Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s The Wild Pear Tree (which will premiere in the Palme d’Or competition he won with 2014’s Winter Sleep) is one of our most anticipated films at the festival, and it’s a welcome presence within the Special Presentations selection. Not so welcome in the State, though, is the latest documentary from Wim Wenders, Pope Francis – A Man of His Word, a Vatican co-production with an Interrotron-like approach that gives His Holiness a direct line to film viewers. Given what is happening in Australia right now, with the prosecution of charges of historic child sexual offences against the Vatican’s third in command, it seems a touch tasteless to be putting this film in the festival, let alone the most cathedral-like venue. Giving its State slot out to Lucretia Martel’s highly anticipated Zama, an interrogation of Spanish colonialism in the late 18th century, would be a step in the right direction.

One of the most surprising inclusions announced for the festival comes in An Elephant Sitting Still, a four-hour debut from the late Chinese director Hu Bo, which was posthumously assembled. Set over the course of a day in the Northern Chinese city of Manzhouli, the film focuses itself on the nature of solitude. Turkish director Tolga Karaçelik’s previous work Ivy had no shortage of flaws, but the 36-year-old’s psychological thriller had moments of potential that threw him on the ‘to watch’ radar, making Karaçelik’s return to SFF with his latest, Butterflies, highly anticipated. The LGBT love story Rafiki, from director Wanuri Kahiu, will come to SFF off of its premiere at Cannes, continuing a run of abroad screenings while the Kenyan director’s film remains banned in her own country. We’re also very excited to see Andrew Bujalski return to SFF with his latest comedy Support the Girls, which sees Regina Hall (Girls Trip) lead a cast of women working in a very familiar-seeming sports bar. His last SFF feature, Results (2015) was a nuanced and fascinating turn on the rom-com, so hopes are high he can achieve something similar here.

Despite some very mixed reviews, Adina Pintilie’s Touch Me Not arrives in Sydney after taking out the Golden Bear, the top prize at February’s Berlinale. Reviews can’t dissuade what has become an essential informal programming partnership: since 2011, every Golden Bear winner has played in Sydney.3

Last year we criticised the festival for a “questionable absence of East Asian films”, with a single film from China the starkest example of the neglect. 2018, by contrast, has seen a huge move in the right direction. Where 2017 featured a total of seven films from East Asia, 2018 has eight from China alone. Alongside Hu Bo’s aforementioned An Elephant Sitting Still, Lav Diaz’s Season of the Devil is one of the most exciting announcements from the Asia-Pacific region. The legendary Filipino director’s latest borders on four-hours (which falls on the shorter end of his works) and captures the Marcos-era in 1979 through a part-noir part-rock-opera.

Kazuhiro Soda looks to build on the fading traditions he captured in 2015’s Oyster Factory with his latest documentary Inland Sea, which continues to explore the lives of a group of fisherman — something he revealed to us when we spoke with him in 2016. Xin Yukun follows up his amusing 2014 Coffin in the Mountain with the noir-heavy Wrath of Silence, while Pengfei Song’s The Taste of Rice Flower and Huang Hsin-yao’s The Great Buddha+ mark two of the more exciting directorial debuts at the festival.

It’s hard to judge the quality of documentaries profiling artists, movements, or figures but degree-of-access is often a fairly reliable indicator. With Stephen Nomura Schible’s Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda there’s a degree of intimacy with the two spending five years together, a period wherein Sakamoto was diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer. Schible was born in Japan and studied under legendary documentary maker Kazuo Hara, making this one to keep an eye on — especially for fans hoping for a documentary doing Sakamoto and Yellow Magic Orchestra’s legacy justice.

It’s a curious year for Australian cinema — no guernsey in Opening Night or Closing Night, eight fiction features spread across the program — and documentaries reign continue to supreme, with the Documentary Australia Foundation Award again the biggest source of new feature-length works from local filmmakers.4 We do want to single out one fiction feature in particular, though: Strange Colours, from one-time 4:3 contributor Alena Lodkina, which had its world premiere late last year at the Venice Film Festival, alongside the aforementioned West of Sunshine.

If last year’s We Don’t Need A Map forced white Australians to reflect on privilege and a collective willful ignorance of Indigenous history, another NITV/SBS production — Dean Gibson’s Wik vs Queensland — looks set to ensure we remember how much has changed within our own lifetimes; it has only been 22 years since the landmark legal decision which grated native title to an indigenous community in Cape York.

The focus on redressing Australian history gains steam in the minor retrospective ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’, which celebrates 25 years of Screen Australia’s Indigenous Department. Curiously, the series comprises only short films (the longest is Ivan Sen’s Wind, which at 34 minutes long doesn’t quite cut it as medium-length), but that decision is truly intended to provide a survey of works across decades. You’ll see some familiar names in the credits of these: siblings Warwick Thornton (with shorts in 1996 and 2002) and Erica Glynn (whose In My Own Words was a crowd favourite at last year’s SFF), Sydney Festival director Wesley Enoch (who wrote and directed the 1998 short Grace), actor/director Wayne Blair (Black Tale in 2002) and ABC Head of Scripted Television Sally Riley (who wrote the 1995 short Fly Peewee, Fly!).

The ever-extensive collection of documentary films boast the most interesting American work at the festival not by someone named Andrew Bujalski: Frederick Wiseman’s three-hour ode to New York’s Public Library Ex Libris and Robert Greene’s hybrid film about racism and labour, Bisbee ‘17. There’s always an inescapable trend of eco-docs but of late the other emerging trend is documentaries about tensions in the Middle East. We noted this in our initial teaser piece, though two films added to the program today seem to be uniquely compelling:

Kurdish-Syrian director (now based in Berlin) Talal Derki’s Of Fathers and Sons heads to SFF on the back of taking out the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance (his second win after 2013’s Return to Homs). Derki follows a father of eight as his 10-year-old son Osama and Osama’s younger brother Ayman begin military training with the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Al Nusa. The documentary looks to offer a rare and intimate portrait of a family within what was one of the most prominent armed opposition groups within Syria. On Her Shoulders, on the other hand, follows Yazidi activist Nadia Murad — whose village in Iraqi Kurdistan was overrun by ISIS militants — as she works to become raise awareness towards the genocide of Yazidis in Iraq.

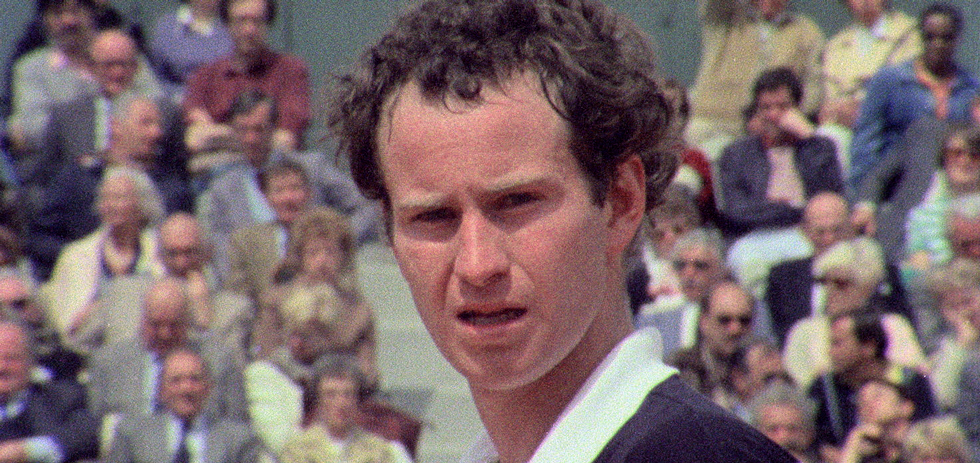

Despite the number of documentary films selected, there’s a distinct lack of notably experimental non-fiction features. Wang Bing’s confronting Golden Leopard winner Mrs. Fang was not selected (despite ‘Til Madness Do Us Part being one of the true highlights of SFF 2014), nor Denis Coté’s part-documentary part-fiction A Skin So Soft. The divisive Harvard Sensory Ethnography film Caniba might have been seen as too confronting for audiences (or, depending on who you ask, too interminable), but the lack of Travis Wilkerson’s Did You Wonder Who Fired The Gun?, which would have bolstered the festival’s undercurrent of history reckoning, is particularly frustrating. We’re also sad to see the exclusion of Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football, which is less experimental but would have paired nicely with Julien Faraut’s John McEnroe cine-essay In the Realm of Perfection, and Khalik Allah’s Black Mother, which wowed audiences at CPH:DOX and True/False earlier this year.

Another aspect of the festival we’re struggling with is this year’s Freak Me Out line-up; The Ranger’s punk rock premise leaves us wishing for another Deathgasm (SFF 2015), while What Keeps You Alive sounds like a lesser Honeymoon (2014). The kitschy local action film Upgrade, from Saw director Leigh Whannell and Blumhouse Productions, might come closest to the usual FMO fare, but it’s outnumbered by psychosexual thrillers (the Ryu Murakami adaptation Piercing and Locarno Jury Prize-winner Good Manners) and anthology films. The team behind The League of Gentlemen serve up comedy Ghost Stories, which sees Martin Freeman investigating the psychic troubles of a gothic England, and the genuinely appealing omnibus The Field Guide to Evil actually brings in the directors we’ve come to expect in this sidebar: Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala (Goodnight Mommy), Katrin Gebbe, Calvin Reeder (The Rambler), Agnieszka Smoczyńska (The Lure), Peter Strickland (The Duke of Burgundy), Yannis Veslemes, Can Evrenol (Baskin) and Ashim Ahluwalia.

Perhaps responding to our ire at the token inclusion of Julian Rosefeldt’s gallery installation Manifesto last year, a bonafide art film sidebar called ‘Flux: Art+Film’ is in this year’s program, in lieu of a substantial second minor retrospective. Curated by producer and SFF Competition jury alum Bridget Ikin (An Angel at My Table, Sherpa), the screening series is a fascinating mishmash of works, each film intended to stand alone rather than function in any clear dialogue. That approach has allowed for films as diverse as Abbas Kiarostami’s final work, 24 Frames, to sit alongside Soda_Jerk’s cut-up agitprop Terra Nullius and Xu Bing’s confronting surveillance film Dragonfly Eyes.5 Other standouts in this strand include The Pure Necessity, Belgian video artist David Claerbout’s de-anthropomorphised version of Disney’s original The Jungle Book, and Sari Braithwaite’s archive film [CENSORED], which takes on the history of film censorship in Australia by repurposing clips excised from films between 1951 and 1978.

While we hope the new Flux sidebar will continue in years to come, we’re glad to see the return of the European Woman in Film series, which has provided some of the best surprises of the festival since its 2016 beginnings. Of the ten films, those that stand out to us this year are journalist Sinéad O’Shea’s Joshua Oppenheimer-produced A Mother Brings Her Son To Be Shot, which documents a confounding act of violence in Northern Ireland, and Georgian filmmaker Ana Urushadze’s debut feature Scary Mother, which we covered last year at Locarno Film Festival.

In light of this sidebar, though, the festival’s Focus on Italy should probably raise a few eyebrows. Of the six films selected, only two are from female directors, and both of those films appear in other sections (Daughter of Mine in the Official Competition and Nico, 1988 in Sounds on Screen).

Aside from the previously announced Essential Kaurismäki main retrospective, discussed at length in our teaser announcement write-up, and the Indigenous shorts sidebar, the remaining retrospective titles are comprised of a scattered grab bag of Classics Restored, featuring both canonised classics and lesser-known films. A screening of a restored 35mm print of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991) is a particular highlight. Widely regarded as a great masterpiece of Taiwanese cinema, prior to its World Cinema Foundation 2K restoration in 2009 and Criterion 4K restoration in 2016 it was only available in a low-quality abridged version. Gaston Kaboré’s God’s Gift (1982) provides a rare opportunity to see an early example of Burkina Faso cinema, the second film ever produced in the nation.

While digital restorations of Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 cerebral sci-fi Strange Days (which screened at MIFF 2017), On Body and Soul director Ildikó Enyedi’s My 20th Century (1988) and Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career (1979) raise the representation of female directors, together they lack the focussed curation of last year’s stellar ‘Feminism & Film’ program of pioneering Sydney female filmmakers. With top-rate retrospective programming at both the inaugural Cinema Reborn festival at AFTRS and Cinema ‘68 film series at AGNSW (Ruby Arrowsmith-Todd’s first as curator), Sydney has been unusually blessed by celluloid offerings in recent months, raising the bar for SFF to match.

While we eagerly await the usual late-minute Cannes additions to the festival program, the decision to focus on lesser-known names in high profile slots is a step in the right direction for broadening cinematic horizons in Sydney. The Competition alone is one of the most unpredictable in years, and for that alone we can’t wait to explore the festival and the works of its filmmakers, in even greater depth.

Disclosure: editors Conor Bateman and Jessica Ellicott were on the Film Advisory Panel for Sydney Film Festival this year. A similar note to this will appear at the bottom of all of the pieces they write during the festival, though they will not write about any of the films they viewed during that process.