It’s become a standard part of our Sydney Film Festival coverage to write about the films we’re most excited to see – as well as those we want others to catch. With 2018’s program amongst the strongest in years, there wasn’t a shortage of films to choose from. In our annual Staff Picks piece, we look to do just that, offering up an eclectic and broad range of films that we think you should seek out when the festival kicks off tomorrow.

Conor Bateman: To my mind, the new art film sidebar, called “Flux”, is easily one of the most compelling features of the program. Though anchored by international festival favourites 24 Frames and Dragonfly Eyes, what appealed most were the lesser-fêted films, like performance artist Amy Jenkins’ Instructions on Parting, an experimental and diaristic account of grief and loss within an American family, and [Censored], Sari Braithwaite’s archival documentary about Australian film censorship between 1951 and 1978. I’m hoping that the latter will prove to be strongly political, but the other Australian film in that sidebar assuredly is: Soda_Jerk’s Terror Nullius, a sprawling account of Australian film history that challenges the pervasive myths of white supremacy and exceptionalism embedded in our national culture. It was saddled with some controversy in Melbourne earlier this year, when the Ian Potter Cultural Trust, which commissioned the film, withdrew support days from the world premiere, allegedly after calling the film “un-Australian” in a private meeting. Let’s hope Soda_Jerk ushers in a renaissance of un-Australian cinema.

One documentary that caught my eye, if only for its title, is Sinead O’Shea’s A Mother Brings Her Son to Be Shot. A deeply confronting look at life in Northern Ireland, told through the struggles of one family in the town of Derry, O’Shea’s film struggles to hold onto the journalistic impulse that prompted filmmaking, and the sense of the unknown throughout — from sudden violence to narrative dead-ends — makes for uneasy viewing on several levels.

Jeremy Elphick: Lav Diaz has become a reliable fixture in Sydney Film Festival programs in recent years (Norte, the End of History, From What Is Before, and The Woman Who Left), which is surprising when considering that he’s easily one of the least accessible filmmakers to play any Australian festival. These days Diaz seems fixated on stylistically reinventing himself with each passing film: moving to (relatively) shorter run times and exploring clearer cut narrative-driven approaches to filmmaking (as in The Woman Who Left). Until Season of the Devil, I’ve never seen anyone describe a film by Diaz as a “rock opera”. While this label is likely a lazily critical descriptor, it suggests another change-up from the Filipino master. As one of my favourite filmmakers, that alone is enough to put Season of the Devil near the top of my ‘to see’ list.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is another of the directors who I’m most excited to see when they pop up in a festival program. Winter Sleep saw him enter a world of narrative grandeur that almost reached the heights of Theo Angelopoulos, drawing on the self-indulgence of a protagonist writing from a place of wealth. His new film, The Wild Pear Tree, also features a writer, though the approach in Winter Sleep looks to be traded out for a character study focused on a man struggling to make ends meet.

I was lucky enough to see Ana Urushadze’s Scary Mother at Locarno last year, where I spoke to the director. Urushadze’s film has a sense of cinematic nuance and narrative complexities that makes the 27-year-old’s debut feature even more impressive. With the experienced Georgian actress Nato Murvanidze in the lead role, Scary Mother is a clear example of a director and cast working in an enviable rhythm. I’d go so far as to say that the product is one of the more cohesive directorial debuts in recent years.

Luke Goodsell: How can anyone not be anticipating Jean-Luc Godard’s The Image Book, after the late-period formal gymnastics of Film Socialisme, Adieu au Langage and punking Agnés Varda and her insufferable street artist collaborator? I’m almost looking forward to laughing at all the bad takes as much as the film itself. Lee Chang-dong’s Burning is another Cannes late-add that I’m excited about, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t curious to see Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote — I’m sure it’ll be bad, but as someone who has always admired his unhinged, swing-for-the-fences ambition, I wish it the best. Elsewhere, Lucretia Martel’s long-delayed Zama is a must, as is Desiree Akhavan’s The Miseducation of Cameron Post. Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, meanwhile, seems to be impassioned and heavy-handed and uneven — which is when he’s often at his best. And lastly, a shout out to Alena Lodkina’s Strange Colours, easily the best Australian movie I’ve seen in some time (even calling it “Australian” somehow does it a disservice.)

Jessica Ellicott: When the full program was announced, the first word I searched the guide for was Transit. There it was, page 13, Official Competition. Christian Petzold’s latest tale of fractured identity premiered to immensely encouraging reviews at the 2018 Berlinale, and is one of my most anticipated films of the year. A few years have passed since I saw his previous film, Phoenix, but its emotional power and complex web of meaning have stayed with me. I expect Transit will have a similar effect. A master of the “loose adaptation”, Petzold’s Transit is an imaginative reworking of Anna Seghers’ 1944 WWII-set novel of the same name, transporting the setting to the present day (but not the characters, who continue to operate in the past).

I’m forever on the hunt for truly good comedies. My best bet, as far as SFF 2018 is concerned, is Andrew Bujalski’s Support the Girls. It premiered only recently at SXSW in March, so it’s relatively fresh on the scene, and early reports are very promising. Don’t be put off by the cleavage-heavy lead still, which likely does not paint the full picture of the sensitivity and comic brilliance that normally characterises Bujalski’s work. I cry-laughed during his last film, Results, and I can only hope to cry-laugh again.

Annabel Brady-Brown: While it’s disappointing to see Cannes highlights like Ulrich Köhler’s In My Room and Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night missing from the last batch of titles picked up by SFF, we can be grateful the festival has added Climax, Gaspar Noé’s latest excess, which scooped the Directors’ Fortnight top prize. From the first choreographed group dance sequence, the film triggers memories of unshackled druggy euphoria and its discontents, via a banging soundtrack and a body-horror homage to some of the genre’s greats — films like Suspiria and Possession, whose influence Noé literally wears on his VHS sleeves in the opening. This gleeful, violent, mass freak-out takes place over one night that down-spirals rapidly; it’s heart-stopping and frightening and sublime.

An absolute Berlinale highlight (with a running time of four hours, which means it’ll never see wider release in Australia), An Elephant Sitting Still is one of the most striking articulations of existential hopelessness to hit screens for a very long time. That it is also a debut feature, by the late Chinese filmmaker Hu Bo, renders An Elephant only more startling. Also set over the space of a single day, the film follows four characters in an economically depressed Chinese town, whose lives intertwine as they each dream of escape. Formally rigorous and maintaining a phenomenally high standard, its four hours of sombre gloom land as nothing short of exhilarating.

Blythe Worthy: Seeking out the hot takes on this year’s program, I was aghast to see the festival itself get involved, with a program strand on the festival’s website titled “Woke Cinema,” supposedly designed to flirt with a politico-cinephilic few. However after a cursory flick through these wokest of films, I was super excited to see some features that yes, have indeed generated a lot of buzz online. Don’t bother trying to get seats at Rafiki, Wanuri Kahiu’s (of 2009’s YouTube-available Afro-Futurist/sci-fi short Pumz) Kenyan love story, as both its sessions sold out almost immediately. Same goes for Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman.

Though wrap-ups of Screen Australia’s 1990s Indigenous shorts initiative Shifting Sands (featuring work by Wesley Enoch, author of The 7 Stages of Grieving and Erica Glynn, winner of last year’s David and Joan Williams Documentary Fellowship) and From Sand to Celluloid (which includes early stuff from Warwick Thornton and Rachel Perkins), are significant additions, similarly to last year’s local retrospectives, again I’m struggling to understand the link between these eclectic films and the festival’s idea of wokeness. Their presence on this particular strand seems a disingenuous afterthought.

Likewise, the “#TIMESUP” strand on the website (striving for that femme dollar), randomly contains, amongst the domestic violence and “domestic dramas,” Desiree Akhavan’s new queermedy The Miseducation of Cameron Post which, if it’s half as good as Akhavan’s debut feature Appropriate Behaviour (SFF 2014) or webseries The Slope, should be a compelling watch. Is this film in #TIMESUP because it stars Chlöe Grace Moretz, an actress known for her refusal to take roles that feel overtly sexual? (This didn’t stop her from starring in Louis CK’s ill-fated creepathon I Love You, Daddy last year). Similarly, Kamila Andini’s magical realist The Seen and Unseen, winner of this year’s Berlinale Generation KPlus Grand Prix, is confusingly present. This kindermeditation on mortality and poetic sensoria, fused with Balinese spirituality and a score by experimental composer Yasuhiro Morinaga, looks to be quite spellbinding, even if it is a somewhat haphazard addition to #TIMESUP.

A 35mm restoration of the late Edward Yang’s 1991 gangster-ballad A Brighter Summer Day, though, is a welcome addition to your festival schedule if you have a spare four hours on the final day. Harnessing a tannin-metallic palette and the muscular performances of over 100 amateur actors, it’s an unfathomably complex examination of class, sexuality, culture and politics in 1960s teddy-boy Taiwan.

Kai Perrignon: Nicolas Pesce made waves a couple years back with his arthouse horror picture, The Eyes of My Mother, a sort of Texas Chainsaw-cum-Eraserhead notable for its striking B&W cinematography and suffocating portent. It’s both exciting and a little disappointing that his new film, Piercing, has neither of those features. Instead, Piercing is a hilarious, demonic screwball comedy about a homicidal young father (Christopher Abbott) trying to purge his murderous impulses by killing an unsuspecting sex worker (Mia Wasikowska). Problem is, he’s a bumbling fool, and she’s just as disturbed — maybe moreso — as him. Pesce shows a knack for injecting the grotesque into comedy, and he matches that tonal mashup with some fascinating formal choices, including the semi-ironic use of classic giallo music cues. Piercing eventually reveals itself to be a slightly over-extended intellectual exercise, but, even with its many flaws, it’s as slyly ambitious as any film you’ll see this year.

Aki Kaurismäki has occasionally been called “Finland’s Jim Jarmusch,” which is both spot on and totally reductive. Kaurismaki’s films do possess the chilly deadpan that descriptor suggests, but even Jarmusch allows his characters to emote every once in a while. The writer/director films his actors not as if they were people, but simply canvases for whatever harshly funny truths he has in mind. Beneath that extreme lack of affectation, however, is a deeply humanistic worldview. Kaurismäki understands that life is an onslaught of miseries, and that the only way to deal with them is to shrug, have a drink, and laugh. Ariel is one of his best films, the story of a coal-miner who heads tries to start anew after his father kills himself. Unfortunately he soon stumbles into a life of crime. Along the way, he falls in love with a metremaid, goes to jail, gets out of jail, and tries to put the hood up on his father’s convertible. If someone drained all the light out of a Soderbergh crime picture but kept the beating heart, they’d get something like this. Well worth seeking out, along with the rest of SFF’s great Kaurismäki program.

Matilda Surtees: Anne-Marie Jacir’s Wajib is a is a welcome addition to the Official Competition, telling a story of generational tension and loss with great humour and relatability. The film is set in Nazareth, home to both the largest Palestinian population and to a tradition in which a bride’s male relatives hand-deliver every wedding invite to their guests. Shadi (Saleh Bakri) is a reluctantly returned son, home from Italy to assist his father, Abu Shadi (Mohammad Bakri), with this duty in the lead-up to his sister’s wedding. Saleh Bakri, a previous Jacir collaborator, and Mohammad Bakri are real-life father and son, and their on-screen dynamic is acted with an enjoyable mix of goodwill and bluff from the senior Bakri, and a deliberate aloofness and seriousness from his son. Playing these traits off against each other with a strong comedic rhythm, the layered difficulties of their relationship provide the dramatic scaffold for Jacir to explore their dispossessions, both personal and political.

Lidiya Josifova: The inclusion of acclaimed documentarian Frederick Wiseman’s Ex Libris – The New York Public Library is but one entry point for the uninitiated, like myself, to Wiseman’s well-established exploration of institutions and the people that frequent them. Having grappled with everything from state mental hospitals (his directorial debut, the controversial 1967 Titicut Follies) to Central Park (1989) to an entire neighbourhood in Queens (In Jackson Heights, SFF 2016), his is a daunting filmography to dive into. Ex Libris is another exciting opportunity to witness the deft hand with which Wiseman whittles down hundreds of hours of raw footage into a holistic, observational (though not objective, Wiseman refutes the cinéma verite label) look at an institution — this time setting his sights on New York’s Public Library, and the rolodex of characters who navigate its halls. And no doubt, as with his previous work, Wiseman will share with us an uncompromising and incisive view of the underlying politics of this new establishment.

By contrast, the debut feature from Xu Bing, Dragonfly Eyes, has also piqued my interest with an altogether different, striking and subversive use for its ‘observational’ footage. Xu condenses 10,000 hours of surveillance camera and live-streamed footage to construct a fictional narrative around a young Buddhist nun who flees her monastery. The vast formal and technical challenges of carving out a visual style and handling narrative pacing, from thousands of hours of disparate footage, along with the inevitable social commentary that arises from Xu’s choice of footage, are an intriguing prospect.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas: If you see only one Brazilian lesbian werewolf movie at the Sydney Film Festival this year, make sure it’s Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra’s Good Manners. Transcending the boundaries of what is traditionally conceived as horror and film form itself as it spans domestic realism and dark, fantastic live-action and animation, this extraordinary São Paulo-set movie is simply like no other. Race, class, monstrosity, and motherhood collide in a way quite unlike anything I’ve ever seen before or am likely to see again. If there’s one single movie that proves the power and potency of genre filmmaking and the creative and ideological capacity it holds, this is it. Other essentials include Isabella Eklöf’s Holiday (although not, perhaps, for trigger-sensitive folks), Sari Braithwaite’s [Censored], and — for something totally different — Emily Atef’s breathtaking portrait of cinema superstar Romy Schneider near the end of her life, 3 Days in Quiberon.

Virat Nehru: I feel this year’s Sydney Film Festival provides an interesting — if not nostalgic — throwback to my younger days of growing up in India, surrounded by innocuous forms of censorship all around me. Take, for example, the film Manto — playing here after its premiere at Cannes in Un Certain Regard. It chronicles the life of one of the subcontinent’s greatest short story writers, Saadat Hasan Manto, amidst the violent backdrop of the partition between India and Pakistan. Much of Manto’s writing was considered obscene for its time — he was charged with obscenity and put on trial — and in certain social circles this perception hadn’t changed, even by the time of my adolescence. As a young teenager, I remember seeking out Manto’s stories out of curiosity, wanting to know what was so scandalous about them, buying paperbacks wrapped in dark and opaque polythene bags from second-hand bookshops as if I was executing some kind of illicit drug deal. One of India’s most accomplished contemporary actors, Nawazuddin Siddiqui plays the titular role of Manto (also appeared in Psycho Raman, SFF 2016, The Lunchbox, SFF 2014 and Gangs of Wasseypur, SFF 2012) and I can’t wait to see what he does with the part under the direction of Nandita Das. Recent biopics coming out of India have tended to be out-and-out hagiographies, but I’m hoping for a more nuanced output in this case.

On the other hand, Kabir Singh Chowdhry’s Mehsampur turns the very idea of a biopic on its head. The film is a stark commentary on the ethics of the filmmaking process and the ego of artists — how far they might go in service of their art. In it, a filmmaker from Mumbai travels to Punjab to make a film about the slain Punjabi singing duo Chamkila and Amarjot, who were murdered in the town of Mehsampur in 1988. Their murder remains unsolved to this day. It’s part docudrama, part mockumentary, and part psychedelic meta-narrative — a kind of thematic bridge between Mrinal Sen’s In Search of Famine and Kamal Swaroop’s Om Dar-b-Dar. It’s a film that actively resists narrative convention, perhaps more so than even Godard’s The Image Book.

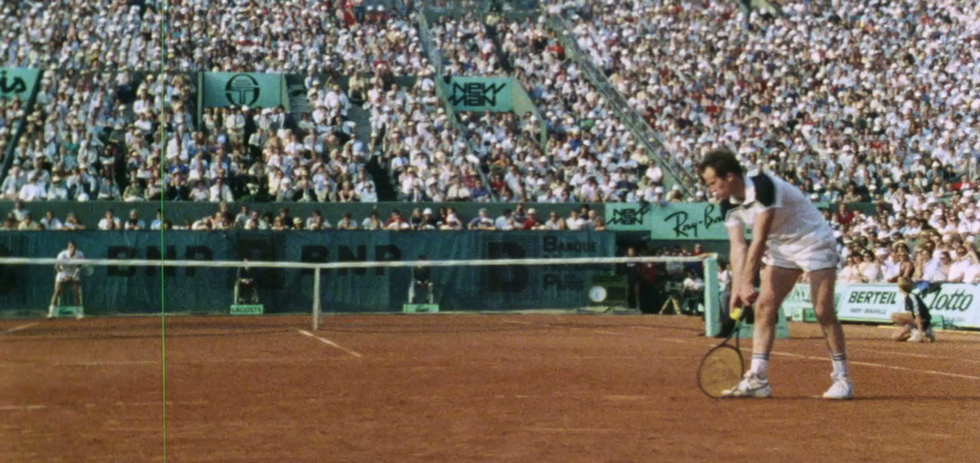

Censorship and the ego of artists have an unlikely thematic union in Mani Haghighi’s black comedy Pig. I absolutely loved Haghighi’s previous work A Dragon Arrives! and I am curious to see how a premise so dark on paper — blacklisted Iranian filmmakers hunted down by a serial killer — becomes fodder for an absurd world ripe for black humour. As a tennis fanatic, I’m also eagerly awaiting Juilien Faraut’s documentary In the Realm of Perfection, which uses 16mm footage of John McEnroe’s 1984 French Open final. Not that I needed further motivation, but Ivan’s fantastic interview with Faraut discussing the film all but sealed the deal.

Read more of our Sydney Film Festival coverage here.