Having premiered at Cannes in the Un Certain Regard section, actor-director Nandita Das’s second feature as a filmmaker, Manto – almost a decade after her first Firaaq in 2008 – is an intriguing portrait of one of the subcontinent’s greatest short story writers of the 20th century, Saadat Hasan Manto. Split across the two-halves of Manto’s life – his pre-Partition days in Bombay and his post-Partition life in Pakistan – the film aims to introduce the man, his stories, and his legacy to a wider audience. One of the most fascinating aspects of the film is how Manto’s short stories and writings are cleverly dramatised and weaved into the broader fabric of the narrative. This blurring of fact and fiction makes viewing the film a somewhat surreal experience as you continuously transition in and out of Manto’s stories and fragmented snippets of his life.

From the violence of the Partition period to the fight against censorship of so-called ‘obscene’ literature and Manto’s friendship with the people in Bombay’s film industry, the film packs a lot in its runtime just short of 2 hours.1

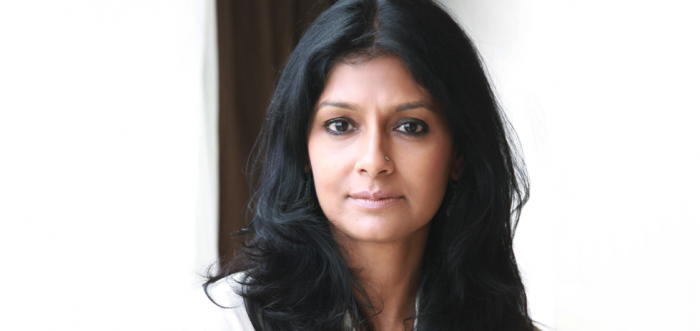

At Sydney Film Festival in June, I sat down with director Nandita Das to discuss the enduring relevance of Saadat Hasan Manto, the challenges of bringing Manto’s words alive on screen and how, even though it’s essentially a biopic of a male literary maverick, it’s the women who steal the show.

You mentioned before we began this interview that Manto’s stories are not emotionally manipulative. What did you mean by that? And what’s the challenge then, in trying to get them across on screen.

I think especially in our mainstream cinema – whether it’s the music, whether it’s the dialogue, whether it’s the way the shot is taken – it is all almost trying to tell you that this is what you must feel. ‘You should now feel fear, you should now feel sad.’ Before it happens, it’s preparing you and telling you how to feel. And Manto, his stories that you read – they are not distant, they are very raw. But at the same time, they are not emotionally manipulative. He just lays it all out as it is. He is not giving his editorial over and on top of it. He is neither preachy, nor is he telling you how to feel.

I’ve tried to do that, keep that spirit alive in the film. Even in the way that I’ve approached the main narrative, there are glimpses of his stories I’ve interspersed it with. Because I feel, if I tell you that he was a great writer, that he was very sensitive, why should you believe me? You need to experience it yourself. Right from the beginning when I thought of the film, I always imagined the narrative to be interwoven with glimpses of his stories. And in his own life, fact and fiction are very blurred. You don’t know whether this is something that really happened or it is something he has made up entirely in his mind. That’s why, even the way the stories are interspersed it feels seamless – the narrative goes into a story and then comes out. As the audience, sometimes you may not know when you enter a story, but you can feel it, and you will know that by the time you are out of it. So, I’ve tried to make it, I don’t know, as Manto-esque as I could. And that’s happened not just deliberately, but also instinctively. I just saw the narrative that way.

We are never quite sure whether we are in Manto’s world or Manto is in our world. His stories and the film’s narrative blend into each other’s worlds. How did you go about executing this idea because the execution of this concept would’ve been tricky.

It was. It’s strange, because when people watch the film, some of them love the ambiguity. I think those who are comfortable with ambiguity don’t mind the fact that they are not told this is a story. And some, who may want it slightly spoon-fed, if I may say so, may feel like, ‘oh shouldn’t you have done the stories in a different colour’ or ‘isn’t there a way you could have separated the stories from the broader narrative?’. And I feel that no, that would defeat the purpose.

In a way I have done that, though,I have used a tiny device to tell you that now you’re entering his story. He looks up straight into the camera and then you kind of go into the story. So, there is a slight bit of indication. But I guess that’s the beautiful thing about cinema. Like life, it’s not all out there and straight-jacketed into boxes. Therefore, I think it was important to blur the line between fact and fiction. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know if it’s a story or if actually happening to him. Because it’s the same feeling when we read his stories. There was a story called Muhammad Bhai, and you don’t know whether it’s just a story or there really was a goon in his area whom he had imagined to be that way – a big, fat, burly figure – but then he turns out to be a really thin guy with an amazing moustache.2 The lines do blur and that’s the beauty of his writing. And I wanted to bring that in the film.

Let’s touch upon the beautiful relationship between Ismat and Manto in the film. It’s a very different kind of relationship and dynamic that unfolds on screen. I think in some ways we are constrained by an imposed morality on Indian cinema, where we don’t often get to see a married man having an open, frank friendship with another woman on screen. I think both Ismat and Manto revel in the fact that they exist beyond the supposed conventional bonds of society. How did you imagine this friendship playing out in the narrative because it’s probably one of my favourite aspects of the film.

In fact, in their later years, their friendship was misunderstood by some.3 I think their relationship was a very modern one. Yes, in today’s time we have men and women who are friends, but in the 1940s – both of them writers, literary stalwarts standing shoulder to shoulder. There were hardly any women at that time active in public spaces, especially in writing. And the fact that she [Ismat] was one among the boys, so to speak, they shared a deep camaraderie. She used to write to Manto, asking him to come back [to Bombay]. And that’s something that’s always intrigued me – why didn’t he go back? Because he really missed Bombay, he missed those friends. He missed the life he had, the respect and dignity he got there. But I guess he was also too egoistic, maybe even too sensitive. He was so deeply hurt, he just couldn’t get himself to return.

Ismat wrote a whole a whole essay titled Mera Dost Mera Dushman for Manto.4 So they had that love-hate relationship, what you call nok-jhonk in Hindi. I could’ve made a whole film on just Ismat and Manto’s story. But because unfortunately, Manto is not as well known as Oscar Wilde or Maupassant or Hemingway, I couldn’t just focus on one aspect of his life. In this film, I’m trying to introduce who Manto was, his words, and his times. There is already enough packed in. Manto deserves a series.

It’s interesting you brought up that Manto is not as well known as Oscar Wilde or say James Joyce. There seems to be a western-centric bias in terms of how we perceive literature globally. Even though there has been Manto, Faiz, Ghalib, Intizar Husain and others from the subcontinent. Do you think as readers people need to widen their lens of what kind of literature there are engaging with?

You are absolutely right. In so much, whether it’s art or literature, pretty much in every field, it’s all so Europe-American centric. Almost white, male-centric if I can say that. Recently, BBC brought out a list of 100 stories that shaped the world, and Manto’s short story ‘Toba Tek Singh’ is the hundredth one to read. So it’s just how it’s been and how it’s perceived. And that’s also one of the reasons why I wanted to do a film on Manto. We need to also share our great talent, our great minds – the people who have really shaped the subcontinent. We ourselves don’t celebrate them enough, let alone the world-at-large.

People have a certain perception of how things were in the 1940s. Also the fact that Manto was Muslim, it pushes him more into that box where people assume a Muslim writer to be – I don’t know – more traditional and more orthodox. But, he was quite an atheist, he never really even went to a mosque. In fact, in Lahore I had seen this beautiful Wazir Khan Mosque when I wanted to shoot. Not that it was anything religious but I just wanted to shoot in that backdrop. I kept trying to dig into the family to see, did he ever go to a mosque? But no. Not at all. The fact that he didn’t ever go to a mosque just shows that there was room for atheism even then.

This is a film about a literary male character, but I felt after watching the film that the women in the movie had much more to do – they had the more nuanced characterisation. I mean yes, Nawaz is fantastic – that almost doesn’t need to be said at this point – it’s almost an unspoken truth that Nawaz just breathes outstanding performances. But Rasika Dugal as Manto’s wife Safia gives a warm sensitivity to her portrayal of the character. It’s not an easy role to play, especially in a male-centric biopic, where the focus is on Nawaz and Manto. And yet, Rasika brings out facets to Safia’s character that don’t seem obvious at first instance. How did you imagine the women in Manto’s life?

In that time, there were so few women in the public space. It’s like you don’t see women. There are three important female characters – his wife Safia, his friend and fellow writer Ismat Chughtai, and his sister Iqbal. Manto was surrounded by women. He was very close to his mother. Of course, we don’t see that because she had died by the time my story begins, which is 1946. But him being surrounded by women is probably one of the reasons his empathy and sensitivity for women is so deep.

I had seen Rasika in Qissa and she was wonderful in it. Also, the resemblance with Safia was quite striking. So, she was actually my only choice for Safia. I didn’t even look elsewhere. The only things we really know about Safia was that she was very supportive, very gentle, very soft spoken. That’s what [Manto’s] family sort of says. There wasn’t much written about her though. Manto, I don’t think, wrote about good women. As he often used to say, “those cannot be the heroines of my stories”. But from the family I got a lot of nuggets.

Manto was a big family man, which is contrary to a lot of mavericks. History has forgiven a lot of mavericks for having many muses. And you think that’s okay, they were great writers or artists so how does it matter? But he was one person who was genuinely caring towards the women who played a role in his life – whether that was his daughter, his wife or his sister. Safia’s character needed to be that foil to Manto’s intensity. To understand any character, you have to understand them through their relationships. You can’t do a character study in isolation. Even to do justice to Manto’s character, it is through his closer relationships that you see his dilemma, you see his contradictions, you see the good and the bad. So, Safia is a very important part of the film.

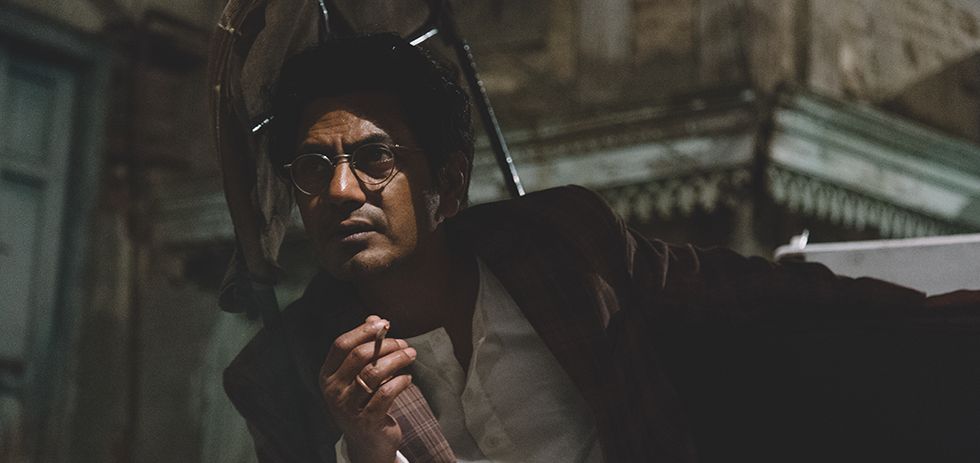

This seems like the most obvious question of all – but finally, let’s come to Nawaz as Manto. What does he bring to the role?

It’s actually a very different role for him. It’s not Nawaz in the way we have seen him before in most of his films. I remember in the beginning people would say, oh he’s a great actor but he doesn’t look like a writer. You don’t connect him with an intellectual character. But again, Manto wasn’t one of those high-brow intellectuals. He actually failed in Urdu. So, a lot of people at that time didn’t even consider him a good enough Urdu writer. He would use English words, he would use Hindi words. He was very much the people’s writer. That’s why he was very accessible. And I think being tied to the language itself for Nawaz was interesting – because a lot of the dialogue in the script were Manto’s real sentences, I didn’t want them to be messed around with too much. And you know, sometimes, as actors you want to make the dialogue your own. So, how do you convincingly say dialogues that could be a mouthful if not said properly? Because many of them were quotable quotes. And yet, they had to feel real, as if they were being spoken, because that was Manto’s language. A lot of traits of Nawaz are actually similar to Manto. He also gets angry quickly, there’s also just that little bit of arrogance, there’s a lot of sensitivity and there’s wit. Nawaz and I had a really good rapport because I had done a lot of research. He was doing Munna Michael and Manto almost simultaneously…

Two very different spaces to occupy at the same time!

That’s where the actor-director relationship also matters. He was in Firaaq as well so I have known him for almost ten years now.

Manto played at the Sydney Film Festival in June and is currently playing as part of the Melbourne International Film Festival.