With 2018 at a close, we’re looking back at the year in film with our annual Staff Picks piece.

Once again, we’ve imposed no real constraints here, so what follows are lists include more than just Australian theatrical releases and display a flagrant disregard for strict world premiere dates. Also incredibly inconsistent: the number of films chosen.

Among the cream of this year’s crop: a double from Radu Jude, a film full of stars, Phantom Thread (yes, it still counts) and a bold call from Alia Shawkat.

Conor Bateman: And to think I thought my list last year was too festival heavy! Of these ten titles, roughly ordered, which make up my best films of the year, only Climax and You Were Never Really Here have had an Australian theatrical run in 2018 (though Burning, Transit and Acute Misfortune can’t be far off!). In last year’s piece I did note my increasing reliance on film festivals over theatrical releases, which I think is driven by the sense of camaraderie (and sheer concentration of films) at Sydney Film Festival and MIFF, but I’m not sure that really excuses the fact that I only made time to see nine new features in a non-festival setting (and two of those were screenings I helped to organise!). That said, the worst new theatrical release I saw was probably the most recent Best Picture winner, so there you go.

Transit (Christian Petzold)

The Dead Nation (Radu Jude)

Burning (Lee Chang-dong)

An Elephant Sitting Still (Hu Bo)

Climax (Gaspar Noé)

You Were Never Really Here (Lynne Ramsay)

Asako I & II (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi)

Acute Misfortune (Thomas M. Wright)

Touch Me Not (Adina Pintilie)

Happy as Lazzaro (Alice Rohrwacher)

HM: Profile (Timur Bekmambetov), First Reformed (Paul Schrader), PROTOTYPE (Blake Williams)

I’ve seen all of the above films only once each but they’ve stuck with me since, blowing my expectations out of the water (Gaspar’s frenetic and enchanting nightmare, Australian art biopic Acute Misfortune) or upending their narrative modes (Petzold’s existential refugee thriller Transit, Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s spaced out rom-com Asako I & II, and Adina Pintilie’s ambitious and heartfelt Touch Me Not).

Though I think there will be a fair bit of consistency throughout these lists around the heavy hitters on the Australian festival circuit (the Petzold, Ramsay, Burning and Happy as Lazzaro), I think it’s worth especially singling out two films that are perhaps less immediately accessible: Hu Bo’s posthumous feature debut An Elephant Sitting Still, a quite extraordinary four-hour tetraptych following a group of strangers in a dilapidated town in the north of China, and Radu Jude’s deceptively simple documentary The Dead Nation, which pairs recently discovered WWII-era portraits from a photographic studio in Bucharest with extracts from the 1937-1948 diaries of Emil Doran, a Jewish doctor living in Romania’s capital; the former uses winding handheld long takes to relentlessly document listless lives and the latter achieves a stunning potency through its stillness, antisemitism and the horrific rise of fascism in Romania is only ever observed through sound (voiceover narration and radio excerpts) — the smiling faces of citizens and soldiers in the photographs depict a damning complicity in true terror.

I think it’s also worth noting some of the best short films I’ve seen, whether at festivals or online, because I think some of the most compelling cinematic work we get each year comes through experimental moving image.

Lasting Marks (Charlie Lyne)

Watching the Detectives (Chris Kennedy)

Silica (Pia Borg)

Wishing Well (Sylvia Schedelbauer)

I Have Sinned a Rapturous Sin (Maryam Tafakory)

Final Deployment 4: Queen Battle Walkthrough (Casper Kelly)

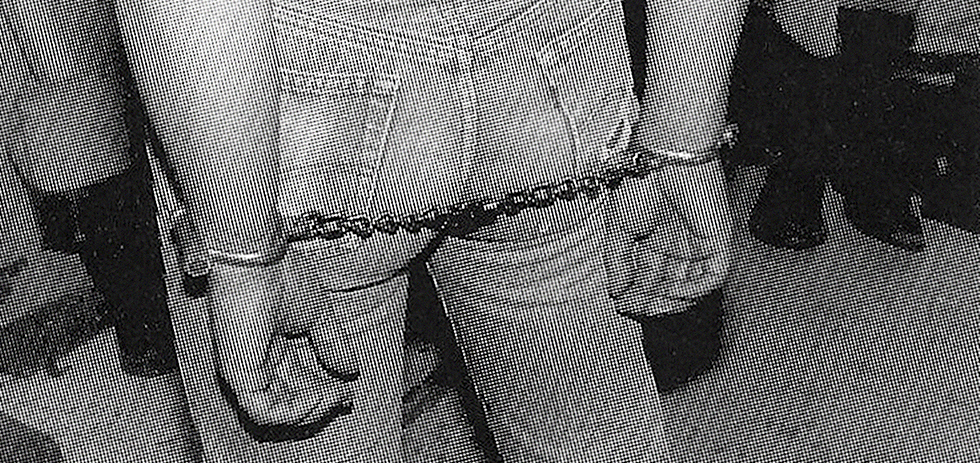

The best short I’ve seen this year hasn’t yet reached Australian shores (though it has to be a shoo-in at a few festivals in 2019), and that’s Charlie Lyne’s Lasting Marks. In his work with Field of Vision (which also includes last year’s Personal Truth), Lyne has moved away from the cinephilic obsession that defined his two features, Beyond Clueless and Fear Itself, but maintains a fixation on memory and media traces. In Lasting Marks, which boasts a 1:1.4142 aspect ratio (that’s an A4 sheet of paper), Lyne retells the infamous arrest and trial of sixteen men under assault charges for participating in consensual sadomasochistic acts during Thatcher-era Britain. Much like the Radu Jude feature I mentioned above, there’s an intention to attack the primacy of the image and uncover suppressed voices, as here we see scans of hysterical tabloid articles, police statements and legal documents run up against the recent testimony of one of those men, who reflects in voiceover on the incident and the way it was interpreted by the media at the time. It’s a very moving experience and one that seems to rhyme with some of the work of American artist William E. Jones, in particular his feature Tearoom.

A pattern among the other shorts is a fixation with broadcasts: Chris Kennedy’s brilliant Watching the Detectives turns an out of control subreddit into a sobering commentary on citizen justice and a desensitisation to acts of terror, Maryam Tafakory’s I Have Sinned a Rapturous Sin rebukes the increasingly outrageous television decrees of Islamic clergy, and Casper Kelly (of Too Many Cooks fame) takes on avatars and identity in Twitch streams in his hilarious and gradually deranged Final Deployment 4. Pia Borg’s Silica is a landscape short set in Coober Pedy (its opal fixation is very much comparable to that of Alena Lodkina’s local feature Strange Colours), with German director Nicolette Krebitz (Wild) playing a location scout for an upcoming Ridley Scott film. Sylvia Schedelbauer’s Wishing Well, which played alongside the Tafakory film at MIFF, is an intense stuttering trek through a lakeside forest, seemingly propelled by the memories of an old man longing for his days as a young boy enchanted with his natural surroundings.

Jeremy Elphick:

Features

An Elephant Sitting Still (Hu Bo)

Empty Metal (Adam Khalil, Bayley Sweitzer)

Asako I & II (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi)

Erased, ___ Ascent of the Invisible (Ghassan Halwani)

The Dead Nation / “I Do Not Care If We Go Down In History As Barbarians” (Radu Jude)

What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? (Roberto Minervini)

Transit (Christian Petzold)

Inland Sea (Kazuhiro Soda)

Terra Franca (Leonor Teles)

Drift (Helena Wittmann)

Zama (Lucrecia Martel)

Long Day’s Journey Into Night (Bi Gan)

The Grand Bizarre (Jodie Mack)

Shorts

Atomic Garden (Ana Vaz)

Gulyabani (Gurcan Keltek)

Mountain Plain Mountain (Yu Araki, Daniel Jacoby)

With History in a Room Filled with People with Funny Names 4 (Korakrit Arunanondchai)

Man in the Well (Hu Bo)

ALTIPLANO (Malena Szlam)

Polly One (Kevin Jerome Everson)

Ardent, Verdant + Hoarders (Jodie Mack)

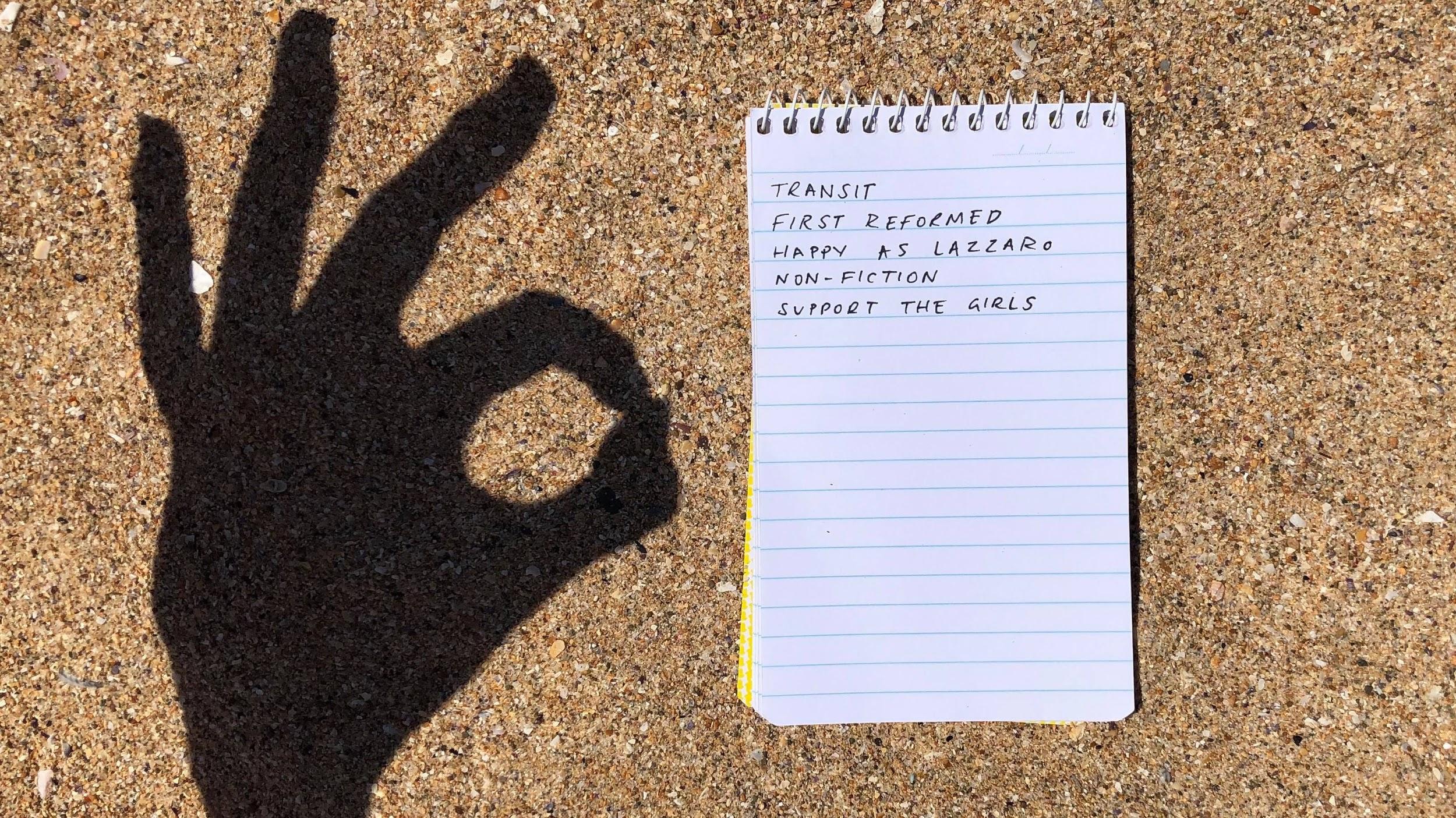

Jessica Ellicott: The films I liked best in 2018 were the ones that most surprised me.

Christian Petzold’s Transit operates on a whole different register to any other film I saw – somehow successfully managing to be both modern and classic, traditional yet experimental. Transplanting the setting of Anna Seghers’ 1944 novel to the present day, but leaving the characters firmly in the diegetic realm of 1942, Petzold upends the expectations of literary adaptation and period drama, redefining the form.

I watched Schrader’s First Reformed not long after I saw his American Gigolo (1980) for the first time. Both very different films. Both masterful works of cinema in their own right.

Happy as Lazzaro further cements Alice Rohrwacher as a director capable of imbuing a uniquely believable magic into her films. Importantly, more a Rivette kind of magic, than the Amelie kind.

I saw Olivier Assayas’ Non-Fiction at AFI Fest about a month ago, and it’s been swirling around in my head since, like Assayas films tend to do. His uniquely playful and self-reflexive command of genre and form, from Irma Vep to Demonlover to Personal Shopper, is, while not immediately apparent in Non-Fiction, nevertheless deeply entwined within the film’s DNA. It’s just more carefully couched under the guise of a relationship drama set in the publishing world.

And Bujalski’s Support the Girls just fucking rules. Not enough people saw Support the Girls. See Support the Girls.

Kai Perrignon: What a Year for Film! First, here’s my quick 26:

1. First Reformed (Paul Schrader)

2. The Other Side of the Wind (Orson Welles)

3. The Tale (Jennifer Fox)

4. Madeline’s Madeline (Josephine Decker)

5. Let the Corpses Tan (Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani)

6. ★ (Johann Lurf)

7. Holiday (Isabella Eklof)

8. Lowlife (Ryan Prows)

9. Mandy (Panos Cosmatos)

10. Dragged Across Concrete (S. Craig Zahler)

11. You Were Never Really Here (Lynne Ramsay)

12. The Passage (Kitao Sakurai)

13. Mission: Impossible — Fallout (Christopher McQuarrie)

14. Ghostbox Cowboy (John Maringouin)

15. Bodied (Joseph Kahn)

16. Suspiria (Luca Guadagnino)

17. The Wolf House (Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León)

18. The Night Comes for Us (Timo Tjahjanto)

19. Black Panther (Ryan Coogler)

20. Support the Girls (Andrew Bujalski)

21. The Debt Collector (Jesse V. Johnson)

22. Mom and Dad (Brian Taylor)

23. Good Luck (Ben Russell)

24. Unfriended: Dark Web (Stephen Susco)

25. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman)

26. Den of Thieves (Christian Gudegast)

Second, here’s a few more thoughts on a few of those entries:

Holiday: One of the best feel-bad films of the year, Isabella Eklof’s Holiday is a clinical, despairing look at a naïve young woman’s gradual understanding of and resignation to the systemic misogyny that rules the world around her. Eklof shoots the increasingly ugly acts of complicity and violence with Haneke-esque long takes that underline a sad inevitability to this story, including the most upsetting act of sexual assault I’ve ever seen in a film. Don’t let the pulpy marketing fool you, there isn’t much genre catharsis buried in this vision of our modern hell. There is, however, a vital reminder that, despite all the screaming on Twitter, we haven’t really fixed our culture’s many ills in any substantive way. At least we have filmmakers like Eklof to spread that idea in a stylish, visceral fashion.

★: Johann Lurf chose an ambitious subject for his feature film debut — a document of (almost) every shot of the stars in the sky committed to film. That premise may suggest something much more academic than what Lurf actually delivers; this is structuralist cinema, make no mistake, but it tests no patience. It’s surprisingly fun!

★ is a history of contemplating history, letting us find joy in the spare moments of recognition that place us in these times and beggar questions that will swirl around in your head for days. There’s the first Star Wars, we’ve reached 1977. There’s Superman, another year has passed. Did we miss Aliens? What did the sky mean to these characters, and has it ever meant the same thing for the audience? Why did no one fake the sky for the earliest cameras? Why did they need it so much in the 80s? Why have we cared so much about the stars for so long?

The Wolf House: The official description of The Wolf House states that it’s about a woman escaping from the infamous Colonia Dignidad (last seen on cinema screens in 2015’s Emma Watson vehicle Colonia) and hiding out in a cabin with two pigs. Not that all that plot is apparent in the film itself, which only throws the vaguest hints towards that story. Not that any of that matters, because The Wolf House works on a purely experiential level. The animation constantly shifts palettes and mediums, flitting between paper-mache stop-motion and textured 2D styles on the walls of the cabin. The aesthetic instability leaves the viewer constantly off-balance as they try to comprehend the nightmare logic that drives all this upsetting imagery. At a certain point, you’ve either got to give in or check out entirely. If you do let it wash over you, what’s left is a disheartening thesis: if one’s world is scary enough, there’s no real escape into fantasy — the mind’s eye can become just as corrupted as the outside world. An aesthetic achievement.

Den of Thieves: Gerard Butler digs deep into his hairy gut to play Big Nick, an ape of a drunken cop who eats food from crime scenes and is on the trail of a troupe of high-level robbers (including Pablo Schreiber and 50 Cent) who intend to burgle the Federal Reserve. Yeah, it’s a Heat knockoff, but who cares when Gerry B is looking so wonderfully puffy when he compares metaphorical dick size with these crooks. Director and co-writer Christian Gudagest is very aware of his limited ambitions, and he’s willing to push those ambitions to the visual and tonal limit, resulting in a borderline-brilliant crime opus that wrings actual emotion and suspense out of its haphazard parts. A glorious shithole of a movie, covered in crumbs and cum and spit and whatever fluid leaks out of highway gutters.

Valerie Ng: 2018’s been a good year for soft animals, with Pooh’s clumsy, enduring figure in Christopher Robin, Fred Rogers’ soft-spoken hand puppet Daniel Striped Tiger in Won’t You Be My Neighbour?, and the willfully polite Paddington bear in his second live-action iteration, Paddington 2. These animals—one tiger, two bears—are this year’s ragtag team of pint-sized philosophers, whose modest ruminations on life, love and good manners hold a degree of unpretentiousness that the most unassuming of humans may be unable to successfully effect. As creatures of certifiable nostalgia, they are, to some extent, the gatekeepers of our childhood— small, sharp reminders of what once was, and what no longer is. Christopher Robin mourns this loss with the greatest world-weariness, and with all its quiet charm, is a film that draws its poignancy from the modesty of its elegy. “Doing nothing often leads to the very best of something,” reflects Pooh, a sentiment that loops seamlessly to the experience of the film, in which one sits quietly in a dark room, watching soft toys amble about in a picture content in its own pleasantness and predictability. And so the film perfectly, to the tee, answers to its own intentions.

Reflections on the passage of time also feature prominently in Happy as Lazzaro and The Old Man and the Gun. In Happy as Lazzaro, the film is sliced in two by one breathtaking shot, leaping forward years in a single cut, gifting the unaging Lazzaro with the sense of deification that accompanies timelessness. The Old Man and the Gun, on the other hand, functions less as a heist film, or a biographical attempt to portray its real-life protagonist, Forrest Tucker, than as a pre-humous elegy for Robert Redford (his Lucky). Lazzaro becomes a passive figure (donkey Balthazar in boy form), such that his encounters with others, photographed blissfully in a fusion of neo- and magical realism, form social statements that pounce with startling poignancy. Redford, on the other hand, has aged in real time, and on the eve of his life and career, is photographed closely, wrinkles and all, in a hazy nostalgic homage that not only pays tribute to his filmography, but also digests slowly one’s transcendence of time—the indelibility of self that carries over from Lowery’s A Ghost Story.

One notable mention that no-one has really seen, or will have the opportunity to see is The Melancholy of Gods, a Macau-commissioned documentary which finds an aspiring filmmaker video-taping her aunt in her mundane, reticent life, with unprofessional but familial attentiveness: shakily cradling a low-res digital camera as her aunt goes about aerobic exercises, as she chops food, recycles clothes, visits relatives, and excursions to the newly built Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge. Macau, a region with a near-negligible movie industry, rarely lends its city to film (bar the occasional blockbuster), and much less its residents. As a result, the film’s gutting pathos lies uniquely in the exceptionality of watching and of being moved by someone who functions metaphorically as a representation of another odd six hundred thousand people, who will soon be lost, undocumented, un-understood, and forgotten, as the years pass, and as time moves on.

My top 15:

1. Christopher Robin (Marc Forster)

2. Happy as Lazzaro (Alice Rohrwacher)

3. The Old Man and The Gun (David Lowery)

4. Private Life (Tamara Jenkins)

5. Paddington 2 (Paul King)

6. Shoplifters (Hirokazu Kore-eda)

7. Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (Frederick Wiseman)

8. Roma (Alfonso Cuaron)

9. Won’t You Be My Neighbour? (Morgan Neville)

10. Burning (Lee Chang-dong)

11. First Reformed (Paul Schrader)

12. Ten Years Thailand (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Aditya Assarat, Wisit Sasanatieng, Chulayarnnon Siriphol)

13. The Melancholy of Gods (Lei Cheok Mei)

14. Eighth Grade (Bo Burnham)

15. Unsane (Steven Soderbergh)

Frazer Bull-Clark:

1. Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (Frederick Wiseman): Another masterpiece from the now 88-year-old filmmaker who can seemingly do no wrong. An engrossing, nuanced and moving portrait of the institution and the city. Wiseman forever.

2. You Were Never Really Here (Lynne Ramsay): Ramsay’s bold, fresh approach to this crime noir is made with such clear-eyed confidence that I was completely gripped. Could be one of Joaquin’s best performances?

3. First Reformed (Paul Schrader): Schrader’s background in the seminary, fascination with the sacred and the profane and love of the transcendental style of Ozu, Bresson and Dreyer collide in this howl of 21st century despair.

4. Custody (Xavier Legrand): What on the surface might appear to be a somewhat dull-looking divorce drama is actually a really effective, white-knuckle thriller. Incredible performances from the whole cast, including some of the best child acting I’ve ever seen. Devastating.

5. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón): Both a small, personal story and a film of epic sweep told on a grand scale. These tensions were what interested me most. Felt like a vast, complex device to explore specific memories of a time and place, rather than simply a ‘period film’.

6. Shoplifters (Hirokazu Kore-eda): Intimate and compassionate, without being overly sentimental. This was a small miracle that crept up on me big time.

7. Her Smell (Alex Ross Perry): A woozy, hypnotic trip. I loved the structuring device of the five acts, each with its own particular visual approach. Elizabeth Moss is towering and fearless in this. Best meltdown of the year by far.

8. Strange Colours (Alena Lodkina): This lyrical gem was the best Australian film I saw this year. Has a wonderful sense of place that winds itself through the internal worlds of the characters. Mikey Young’s score is ace.

9. Support the Girls (Andrew Bujalski): A nicely subversive comedy, which finds a sweet spot between being formally and tonally experimental and broadly entertaining. Regina Hall might give my favourite performance of the year.

10. John McEnroe: In The Realm of Perfection (Julien Faraut): This somehow manages to be a fascinating character study, physiological analysis of tennis, playful deconstruction of the filmmaking process and in its final act – a dramatic sports drama. The opening credits sequence – a montage of McEnroe beginning to serve, set to a live version of Sonic Youth’s “The Sprawl” gave me chills. Can’t wait to watch this again.

Honourable Mentions: Hereditary, Sweet Country, Transit, Adam Sandler: 100% Fresh, Terror Nullius, Non-Fiction.

Ivana Brehas:

Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson): My favourite film of the year. There are a lot of things I could say about it, none of which could, in my heart or mind, wholly do it justice. I found its connection with health issues like eating disorders, perfectionism, control issues and burnout to be particularly resonant. There is a lot of love in my heart for Paul Thomas Anderson.

Laissez bronzer les cadavres (Let the Corpses Tan) (Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani): Cattet and Forzani’s mind-bending genre masterpiece was my first exposure to their work, and I utterly adored it. The blue of that sky is like nothing I’ve ever seen before. Definitely reawakened my love for film as a sensorial medium, as opposed to simply a narrative one. This is a film that is experienced by the body.

Yours in Sisterhood (Irene Lusztig): I’m hesitant to use the term “intersectionality” here because it has often been thoughtlessly employed as a buzzword, but it is a standout feature of this film. I approached Yours in Sisterhood with a kind of self-righteous contempt, presuming that its content would reflect the second-wave, white supremacist, cis- and heteronormative ideologies of its subject, Ms. magazine. I was pleasantly surprised to find a film that was, instead, openly critical of the very magazine it was about. In focusing on letters and submissions that were not accepted by Ms., the film sheds light on the voices that were being suppressed by the 1970s “feminist” movement. Having them read by contemporary women generates contemplation about what’s changed and what hasn’t, and how far we have to go. The letters are varied in tone — amusing, heartbreaking, enlightening, frustrating, surprising — but the experience of the film is altogether inspiriting.

Burning (Lee Chang-dong): Another deeply physical cinematic experience, much like Let the Corpses Tan; one that I struggle to articulate or intellectualise. Steven Yeun is luminous and astonishing. My memory of the feeling of watching the film is perhaps more potent than my memory of the film itself.

Blaze (Ethan Hawke): Ethan Hawke, I love you sir. I think this film was really cool and I had a good time watching it! It feels like a lullaby of sorts. It also made me want to go and live in the woods with Ben Dickey. I’m a bit of a sucker for dreamy stuff.

Duck Butter, dir. Miguel Arteta

“Male reviewers don’t get DUCK BUTTER” — Alia Shawkat, 2018

H/M: Sebastián Silva’s Tyrel, a good film (which I reviewed for 4:3, so I won’t repeat myself). Begrudgingly, Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, which I only decided I liked about a week ago (save the planet; don’t self-flagellate). Road-tripped to Adelaide to see Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, so I guess I have to include it — Yalitza Aparicio is mesmerizing. I don’t know if I could ever watch it again, though. It was breathtaking but very stressful. Between that and First Reformed, 2018 really was the year of anxiety about the fragility of life. I feel a need to round this list off to an even 10, so for the gays (and/or the fans of powerhouse leads) I’ll chuck in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Favourite. A lesbian film, written by an Australian, and directed by a Greek — as a queer Greek Australian, how could I not mention it?

Virat Nehru: I have been agonising over how to structure my picks for quite some time. Part of the anxiety stems from my desire to champion Indian cinema. It usually gets a raw deal whenever most international critics pick their end of year ‘best of’ lists. The way this list works is that I have divided it with an equal split between international titles and Indian films. I’m not sure if it’s the right way. But then again, it’s my list so you will just have to deal with it I guess.

3 Faces and The Wild Pear Tree: Two films that couldn’t be further apart in their sensibilities, but over time and with subsequent viewings, I’ve come to see them as cinematic siblings of a kind. Panahi and Ceylan are weird opposites – to the extent of the kind of humanism their films seem to embody. Yet, you can extrapolate from one and reach the other’s cinematic language. The Kiarostami touches in 3 Faces were incredibly poignant, a way for Panahi to not only pay homage to what’s come before, but also add to the legacy and take it forward with the kind of delicate understatedness that only he can. I’m also increasingly in awe of Ceylan’s ambitiousness in attempting the grand narratives of 20th century novels on celluloid. The sort of chapter-by-chapter, episodic way of structuring narrative is where he is most effective. I still don’t know what that long discussion between the two schools of thought in interpreting Islam was doing in The Wild Pear Tree, but as a chapter in and of itself, it was unexpectedly fascinating.

Vada Chennai and Bodied: Two films that I felt could be longer despite their already long runtime. Director Vetrimaaran stated in an interview, his first cut of Vada Chennai was almost five and a half hours. This feels long, but when you actually see the final product – a version which is chopped down to almost two and half hours – you can tell why the film would have benefitted from a longer runtime. There is so much happening on screen. Both, the audience and some of the scenes, could have done with more breathing room. It’s an epic gangster saga. Think Kashyap’s Gangs of Wasseypur but with leaner editing, less indulgence and an equally powerful motion picture soundtrack. It’s planned as a trilogy, so strap yourselves in. I’m happy to admit Joseph Kahn’s Bodied took me by absolute surprise. So much that I saw it twice at the same film festival (MIFF). I definitely wasn’t prepared for its take no prisoners attitude, but more importantly, how genuinely funny it was.

October and Leave No Trace: In my review of Karan Johar’s Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, I had mentioned how mainstream Hindi cinema was looking to move away from love stories and instead, explore stories about love. Finally, with Shoojit Sircar’s October, that has now come true. The central premise – of how the aftermath of a traumatic incident brings unlikely people together – is explored with such sensitivity in the script by Juhi Chaturvedi. Special mention to a standout performance by Gitanjali Rao. Dealing with trauma in a kind, sensitive and nuanced way also forms the bedrock of Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace. The film is quietly affecting and stays with you for a while, like an affirming bedside companion.

Phantom Thread and Andhadhun: Talking of bedside companions brings me to Phantom Thread. 2018 has been such a long and disorienting year that I had totally forgotten this released in Australian cinemas earlier in the year. I’m all for the dark comic tone of this film. Also, I’m terrified of mushrooms now. But if I’m being honest, nothing beats the dark comic tone of Sriram Raghavan’s Andhadhun. It’s a dark comedy disguised as an edge-of-your-seat crime caper disguised as a genre mashup. And this film has Tabu. Honestly, that should be enough endorsement to see a film. Everyone should just give all awards ever to Tabu. There is no debate on this. I must highlight a specific scene midway in the first-half – where the characters have to physically perform to a musical interlude without any spoken dialogue – which is easily my favourite scene from any film this year.

Cold War and Tumbbad: In both films, I was initially more taken in by their visual aesthetic than the emotional core of the narrative. In my first viewing, both films didn’t connect with me emotionally as much, even though I was immediately in awe of how they have been shot. It’s taken me three viewings of Cold War to get the pulse of how the narrative plays with songs as emotional beats. One thing that hasn’t changed is my belief that Joanna Kulig is an absolute goddamn star in this. Tumbbad creates this fairytale-like world with intricate and painstaking detail and the more I re-watch it, the more I fall in love with its moral fable roots.

Sudani From Nigeria and Ee.Ma.Yau: Malayalam cinema tells the best stories and in most unexpected ways. Take debut director Zakariya Mohammed’s Sudani From Nigeria. You think it’s going to be a sports drama and then just like that, it completely pivots and becomes a low-key family drama exploring cross-cultural exchanges. You forget how good the film is because of how understatedly the drama plays out. It also has one of my favourite acting performances of the year by Nigerian actor Samuel Robinson. Director Lijo Jose Pellissery follows up Angamaly Diaries – one of the best films of 2017 – with Ee.Ma.Yau – one of the best films of 2018. Pellissery has quickly emerged as one of Indian cinema’s most assured directors. A death in a rural community becomes the catalyst for Pellissery to craft a satire that explores politics, religion, traditions and the absurdity of human existence.

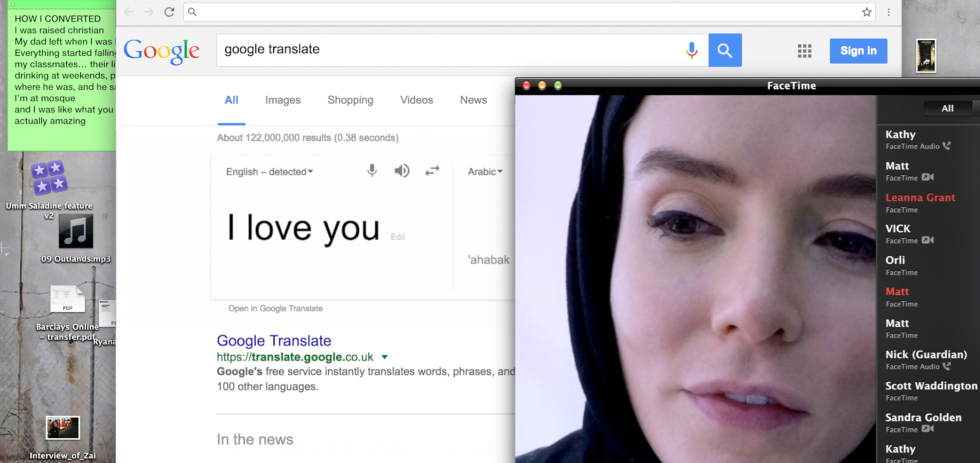

Profile and Mehsampur: Two films that play as much with the visual form as with our narrative expectations. Profile genuinely surprised (also terrified) me with some of the directions it went into. I was invested in not only what was unfolding on screen, but also the ethics of the process. Mehsampur, on the other hand, is entirely concerned with the ethics of the filmmaking process and the lines a filmmaker would be willing to cross to get that one perfect shot. It has shades of Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane/In Search of Famine (1981). Sen recently passed away this week, but Mehsampur keeps his legacy alive in trying to find new ways of pushing the boundaries of the visual medium.

Pariyerum Perumal: And finally, we are at Periyerum Perumal. Mari Selvaraj’s film explores India’s deep rooted caste anxieties through an intimately personal lens. The result is an powerful cinematic experience that doesn’t wear its politics on the nose. In a year where political narratives were everywhere – think BlacKkKlansman or Sorry To Bother You – it’s Selvaraj’s more personally grounded narrative that has the most impact. Special shoutout to music composer Santhosh Narayanan who had a stellar 2018, giving three back-to-back top notch motion picture soundtracks: Kaala (Pa Ranjith), Pariyerum Perumal (Mari Selvaraj) & Vada Chennai (Vetrimaaran).

3 Faces (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

Andhadhun (Sriram Raghavan, 2018)

Bodied (Joseph Kahn, 2018)

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2018)

Ee.Ma.Yau (Lijo Jose Pellissery, 2018)

Leave No Trace (Debra Granik, 2018)

Pariyerum Perumal (Mari Selvaraj, 2018)

Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2018)

October (Shoojit Sircar, 2018)

Sudani From Nigeria (Zakariya Mohammed, 2018)

Vada Chennai (Vetrimaaran, 2018)

The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2018)

HMs: Profile (Timur Bekmambetov, 2018), Mehsampur (Kabir Singh Chowdhry, 2018), Tumbbad (Rahi Anil Barve, Adesh Prasad, Anand Gandhi, 2018

Ivan Čerečina:

1. Gregory Markopoulos + The Cantrills: The Language of the Image (Melbourne, July 2018)

I said my piece on these exceptional screenings here and here.

2. Transit (Christian Petzold)

3. On The Beach At Night Alone (Hong Sang-Soo)

With every new Hong film, I am reminded more and more of Laurence Sterne’s quixotic author figure in his wonderful anti-novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. There, in an effort to recount the history of his life, the author doesn’t know where to begin, and instead mounts digression upon digression on philosophy, art, religion to ward off the task. In so doing, he inadvertently provides a portrait of himself. This is not to say that Hong’s characters don’t mirror his life at all – they may well in some capacity, I’ve not met the man. But rather, by sheer force of repetition, technical cues and endless narrative recursions, what emerges feels like as clear a demonstration of authorial “touch” as exists amongst modern filmmakers, which ought to be distinguished from “style” precisely in terms of its ability to reveal something of the maker.

4. The Image Book (Jean-Luc Godard)

With the recurrent direct citation (see image above), The Image Book to my mind was another demonstration of how important André Malraux and his art history books of the 1940s and 50 have been for the Swiss-French director’s work since his Histoire(s). Malraux wrote of the “imaginary museum” that the invention of the illustrated art book had created for both art goers and artists, the meeting of photography and the printing press in these books of images demonstrating the metamorphoses of art history like sped up footage of a flower in bloom. Godard continues to extend this Malrucian concept to the very writing of history, his own historical consciousness seemingly composed by an imaginary cinematheque whose images he sorts through before us.

5. In the Realm of Perfection (Julien Faraut)

Julien gave a very generous interview to the site in April of this year.

6. Zama (Lucrecia Martel)

Esther Allen, the English translator of Antonio Di Benedetto’s Zama, has written an excellent essay on Martel’s adaptation and its elliptical subtleties. With Transit, the other great adaptation of the year.

7. Terra Franca (Leonor Teles)

Flaherty in a small Portuguese fishing village. A revelation from this year’s Cinéma du réel.

8. L. Cohen (James Benning)

9. Strange Colours (Alena Lodkina)

“The technique of Rossellini undoubtedly maintains an intelligible succession of events, but these do not mesh like a chain with the sprockets of a wheel. The mind has to leap from one event to the other as one leaps from stone to stone in crossing a river. It may happen that one’s foot hesitates between two rocks, or that one misses one’s footing and slips. The mind does likewise.” – André Bazin.

See more from our end of year coverage here.