In 2016 I wrote a series of pieces at Fandor Keyframe about video essay form, all of which ran under the banner ‘The Video Essay as Art’. A throughline in my writing was an argument that video essays should be less didactic and more geared around a process of discovery. Videos in this vein tend to be at a remove from essays commonly found on YouTube and even those made by academics. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that both of these groups want to educate their viewers in some way. YouTubers break down sequences, genres and (mostly popular) films, arguing for why an approach or work is ‘good’. Academics tend to use video to show how films operate in relation to theoretical concepts (some, of course, adopt a more discovery-oriented approach).

For video essays outside of the YouTube/academia divide, 2016 proved to be a year of turbulence. Press Play shut down over at Indiewire in April (though they have maintained they will re-emerge, hopefully as more than just a running collaboration with No Film School). Publications on the whole are publishing very little: MUBI Notebook published 10 video essays in 2016, Sight & Sound and Filmkrant both ran only 7. RogerEbert.com published around 12 video essays, though all by Scout Tafoya. [in]Transition, the academic video essay journal run by Catherine Grant, published 15 video essays last year.1 Fandor Keyframe is the outlier, with around 130 videos published in 2016, the highest number since they began publishing video essay content in 2010.

Though Fandor was the major publisher last year, many of its video essays strayed away from the analytical approach they had become known for, shaped by the work of Kevin B. Lee. In 2016 they, like many websites (film and otherwise), moved to a social media first publishing model for video content. Facebook video has become an all-powerful force for businesses to engage consumers, assisted tremendously by the 3-second view count. Instead of detailed video-based film analysis, social media driven video essays have become far more simplistic and didactic, bite-sized film trivia over memorable ideas or arguments. Rather than adopting the hyper-personal (and successful) approach of many didactic YouTubers, though, chasing social media views has resulted in a watering down of any essayistic voice.

Take, for example, two videos by Jacob T. Swinney, released over a year apart. The Dutch Angle (September 2015) is a three-minute supercut that effectively and playfully tracks the full spectrum of Dutch angles in cinema, using nothing but film clips and a musical score. 6 Uses for the Bird’s-eye Shot (October 2016) is a one-minute supercut. It too uses film clips and a score but adds, on top of this, text which explains the broad meaning of each ‘use’ of the bird’s-eye shot. The 2015 video is memorable, unique and engaging because it isn’t focused on teaching us a short, sharp lesson about film form, rather it allows the viewer to see—for themselves—the patterns that emerge when filmmakers use the Dutch angle. The 2016 video takes the opposite approach, telling us what to see and think without giving us time to contemplate anything. It’s an approach that is indicative of a push to treat video essays like Tasty videos: here are the ingredients, here’s how they fit together, in sixty seconds or less.

I asked Swinney how he felt about trying to approach video essays with a social media audience in mind.

“I find it to be a little restrictive as far as creativity goes: having to keep the videos brief, hammering your points quickly, making everything easy to digest, etc. But it is sort of paradoxical because, with this set of restrictions, you have to become even more creative and innovative. You have to find new ways of creating and expressing ideas. For example, with Movie Music Playlists, the Facebook-first model inspired me to create the radio dial graphic rather than using a more traditional supercut format.”

It’s clear to see that Swinney has been successful in developing a more social-media oriented visual approach in his videos. Take, for instance, Cats Die Funny, Dogs Die Sad, which uses an emoji-filled line graph to illustrate a clear tonal disparity with regards to the depiction of the deaths of cats and dogs. Joost Broeren’s Man // Woman // Mirror is much the same, charting the clearly gendered attributes of select film clips on an axis. LJ Frezza’s amusingly edited Paul Verhoeven’s Mass Media takes a different approach, wholeheartedly embracing the short attention span of the Facebook medium.

More personal and unique video essays are hampered by the restrictiveness of a social media mindset. Jessica McGoff’s Andrea Arnold’s Women in Landscapes is a well-written video essay which cleverly places a focus on sound design through an absence of voiceover, but on-screen text distracts from frame composition. That said, McGoff is one of the better working video essayists in terms of voiceover. Her conversational tone and intelligent analysis in video essays on The Terminator (one of 2015’s best, sadly unavailable to watch now), Kelly Reichardt and Takashi Miike’s Audition, have marked her as someone to watch, yet the Facebook approach has seen her go from making 10-minute long video essays to a 2-minute one, jettisoning voiceover in the process. Interestingly, despite their wildly different subject matter, both McGoff’s video and LJ Frezza’s Verhoeven cut have the following in common: on-screen text, clips from multiple films, less than two minutes in length. Frezza’s video engages with the chopped up nature of media and propaganda in Verhoeven’s films, so his rushed approach works. For McGoff’s video, though, the restriction of duration runs counter to the contemplative nature of much of Arnold’s filmmaking.

The question raised by these examples is a difficult one: how do we reconcile good video essay practice with engaging a larger audience? A video essay that seems to answer this, playing off of a Facebook-first mentality to create something deeply satisfying to watch, is Leigh Singer’s impressive (and six-minute long!) Why ALIENS is the Mother of All Action Movies. Singer places text next to his chosen clips, never encroaching on the image itself, and plays with the position of image and text within the frame throughout. With no external musical score, he allows James Cameron’s film to almost speak for itself despite Singer’s own chopped-up analysis. If we are to take anything away from Singer’s Facebook-first video, then, it is that length should not be shied away from.

If we assume that Facebook readers only ‘watch’ between three and twenty seconds of a video on average, essayists shouldn’t necessarily be compelled to make a video closer to 2 minutes than 20.2 You just need to hook people at the start. Singer’s first 14 seconds adopt the text on-screen approach that many of the Facebook-first video essays use for their whole runtime, but after that he moves into a more detailed argument.

Singer’s video is one of five Fandor videos posted to Facebook to get over 1 million views between August and December last year. The others are less video essays than catalogues, clip reels playing off of the existing fanbases of famous actors: Benedict Cumberbatch (video by Kevin B. Lee), Kristen Stewart (video by Kevin B. Lee), Margot Robbie (video by Kevin B. Lee) and Michael Fassbender (video by Daniel Mcilwraith).3 These videos are worth studying because of their huge reception but only Singer’s—with its engaging thesis, unique use of framing and text, its duration—offers a path forward for engaging analytical video essays on social media.

In early 2017, Fandor Keyframe began removing older video essays from their website following advice from their in-house legal counsel. Over 200 videos have been removed so far, though some of those have since been reuploaded. The legal question, as far as I am aware, primarily concerned the use of music in video essays, which could have placed a greater burden on Fandor to prove fair use under American copyright law.4 Fandor is currently in the process of reviewing and rescoring some of these removed video essays. As it stands, though, many of the best video essays of the last few years are currently unavailable to watch online. Video essayists have begun uploading videos originally made for Fandor on their personal accounts, some of which are collected in the Vimeo album Backdor, hosted by Catherine Grant’s online forum Audiovisualcy.

The enforcement of stricter copyright terms on video essayists has impacted on output, not in terms of number of videos produced (Fandor looks set to match their 2016 total at minimum) but in terms of quality. Instead of moving towards film criticism, many of the newer Facebook-first videos from Fandor merely relay information. As a result, these videos have not pursued a representational strategy like Singer’s Aliens video essay, instead following on from the other recent million view videos.

Despite the push to more social media friendly content, last year saw a host of video essayists creating compelling, provocative and personal works. What follows are some of the best I saw in 2016.

Who Deserves the 2016 Oscar for Best Picture? by Kevin B. Lee (Fandor Keyframe)

The Oscar season videos that were produced by Lee for Fandor were interesting and instructive viewing, though last year one of those videos went beyond conjecture and comparison, delivering an intelligent and rigorous analysis of one film in particular, Adam McKay’s The Big Short, and painting it as a thoroughly modern essay film.

Kiarostami: The Anti-Supercut Artist by Kevin B. Lee (Fandor Keyframe)

In the wake of the passing of Iranian master filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, video tributes poured out. The best among them all, though, was Kevin B. Lee’s Kiarostami: The Anti-Supercut Artist, which served as a wonderfully anti-clickbait tribute and also acted as a call for more subtle, languid video essays in the social media realm.

The Thinking Machine: Death-Drive by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin (de Filmkrant)

Martin and López use only thirty seconds of on-screen text at the start of the video to establish clear and intriguing parameters for viewing Jack Cardiff’s 1969 film The Girl on a Motorcycle, then show us five minutes of carefully selected shots which serve to reinforce their initial hypothesis. It’s nice to see a video essay that never feels the need to hand-hold, instead letting the viewer engage with the images both on the video essayists’ terms and their own.

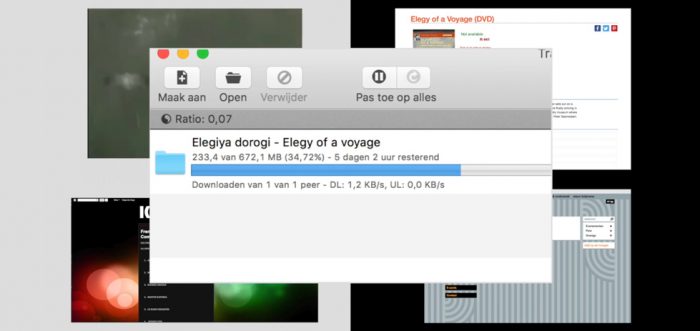

Elegy for a Lost Film by Dana Linssen, Jan Pieter Ekker and Menno Kooistra (de Filmkrant)

Produced for this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, Elegy for a Lost Film is a meta-video essay that charts the frustration of the essayists in their search to find a legal and decent-quality copy of Alexander Sokurov’s Elegy of a Voyage, prompting questions of artists’ rights, film archives and memory.

UN/CONTAINED: A Video Essay on Andrea Arnold’s 2009 Film FISH TANK by Catherine Grant ([in]Transition)

In my second piece in my Fandor column, I wrote about the ‘process’ of video essays, in that essayists who convey their own investigation and discovery in their videos are far more intellectually interesting than essayists who just present information in the form of a lesson. Catherine Grant’s UN/CONTAINED is a great example of the former; as I wrote in my earlier piece, Grant’s video “follows her line of thinking through with screen text, repetition of shots and sound analysis to reach a point of discovery that’s felt on the part of the viewer as well.”

Do Pay Attention to That Man Behind the Curtain by Mariska Graveland (de Filmkrant)

I singled out this video in my piece on supercuts, and it’s by far one of the stronger supercuts I have seen. To quote myself: “What’s immediately apparent here is that, unlike the makers of many other supercuts, Graveland lets her clips breathe. From Buster Keaton in Sherlock Jr. to the famous “cigarette burns” sequence in Fight Club, the extended clips allow for more meaningful leaps in logic.”

The Colors of Daisies by Joel Bocko (Fandor Keyframe)

A minute-long supercut of shots from Věra Chytilová’s kaleidoscopic Daisies organised by colour alone. It’s a simple idea but so very well executed

Strange Adventures in Film Language by Tope Ogundare (Fandor Keyframe)

A delightful jaunt through mistranslations, lazy subtitling and subtlety-eroding dubs. Rather than promise any overarching message or lesson in his analysis, Ogundare instead playfully walks us through a series of odd disconnects he discovered.

ADAPTATION.’s Anomalies by Jason Mittell ([in]Transition)

The video essay as conspiracy theory, as Mittell moves beyond the surface level analysis of the metafiction at work in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation. and towards an obsessive analysis of the film’s anomalies.

Fear Freezes the Soul by Filmscalpel

Trust Filmscalpel to always appear on year-end lists, so strong is the quality of their work (not to mention their curation). Fear Freezes the Frame is a video essay about the use of stillness (note: not still frames) in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.

What Does BLUE Sound Like? by LJ Frezza (Fandor Keyframe)

One of the very few analytical video essays (read: not supercut) to focus on film sound design. Calling to mind Cristina Álvarez López’ video Sound Samples of the Wind, Frezza looks at recurring aural motifs in Derek Jarman’s Blue, his on-screen text working both in tandem and in response to the audio mix.

A Theory of Film Music by Dan Golding

It’s rare to see video essays working in dialogue, since so many video essays that reflect on the form tend to do so as a survey (Kevin B. Lee’s What Makes a Video Essay Great? and Ian Garwood’s recent The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism come to mind) rather than a specific rebuttal. Golding, an Australian academic, takes on The Marvel Symphonic Universe by Brian Satterwhite, Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou, fleshing out some of that video’s assertions about temp tracks in film scoring.

Finally, I want to highlight a few recut videos. As I wrote in my very first piece in my Fandor series, “the line between video essay and video art is blurred when we look at the imaginative re-purposing of texts” in the form of recuts.

Have A Nice Daze by Ivana Brehas

Brehas impressed in early 2016 with Gone Girl: A Greek Tragedy, matching Gillian Flynn’s screenplay for Gone Girl with text from Euripides’ Medea. This recut, though, is in a completely different vein and has really stuck with me. Brehas takes nine behind-the-scenes interviews with some of the young castmembers of Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused and arranges these interviews within the one frame; grid-like, they call to mind the opening credits of The Brady Bunch.

Whiplash: From Short to Feature by Jacob T. Swinney

A seemingly simple idea—comparing Damien Chazelle’s Sundance-winning short and the same scene in his feature-length follow-up—that is a deceptively intricate piece of work. Rather than just have them side by side, like the several Psycho original/remake videos out there, Swinney cuts between the two versions of the scene, maintaining the rhythmic flow of the scene.

Honolulu Mon Amour by Nick Watt ([in]Transition)

Magnum P.I. reframed as Resnais, Watt’s Honolulu Mon Amour is an intoxicating work that suggests an oft-unacknowledged poetry lurking beneath the surface of the Tom Selleck television series.