One of my earliest memories, pulled from the misty heaths of a mostly untroubled and largely forgotten childhood, is of myself, cross-legged, peering through the crack of the living room door as my father and my teenaged cousin watched a grainy VHS copy of The Toxic Avenger. Dad, a horror fan who has relayed to me vague details of B-horror flicks which may or may not have ever existed for as long as I can remember, was clearly thrusting this same initiation ritual onto my cousin. I do not recall ever being so frightened in my life. It is my earliest recalled film experience, eclipsing every formative Disney moment with an uncharacteristic starkness in my mind’s eye. Friends will recall with great clarity the sense of retrospective joy at hearing the Aladdin soundtrack; all I have is the fractured memory of Toxie feeding a woman into an industrial washing machine. They are, fundamentally, identical emotions.

The VHS hums with a kind of phenomenological significance that the DVD or the Blu-Ray, with their immaculate, multiplexed video streams, can never aspire to. The experience of watching a high definition movie in 2014 is one of near-perfect fidelity. We see every drop of perspiration and every pockmark. Increased frame-rates mean that not even movement is illusory. Even the most outwardly fantastical films are rendered in obscenely mundane detail. Do we need to see the flutter of Bilbo Baggin’s eyelash delivered onto a 4K display at forty-eight frames per second? It’s the fundamental contradiction of video technology: as we approach total fidelity, the realness of film recedes. Superman’s flight in Man of Steel is the spectacular conclusion of trillions of man-hours of meticulous VFX work, but it’s only fractionally as visceral as when Christopher Reeves first took off in 1978.

Watching anything but a new, completely unblemished VHS is like descending into a peyote fever-dream. Every minor imperfection on the tape intrudes onto the film as a glittering explosion of colour and distorted image. The sound stretches out into a hollow groan, and clusterbombs of signal noise scatter across the curve of the picture. As the film is watched and rewatched, it becomes less and less visually coherent. Watching recorded cartoons one had seen dozens of times was an exercise in both perception and, inevitably, memory. You had to ask yourself whether the quivering mass of colourspace in the corner of the screen had always been there – whether the creator had intended its existence or whether it was a smudge of dirt on increasingly atrophied magnetic tape. If 35mm film possesses character, tape has implacable, ghostly presence; vaguely menacing in retrospect. It is movie as monolith: a gargantuan, sputtering concretion which is simultaneously ephemeral and eternal. It is crumbling, but will still exist in some hazy form when the Sun is dead and all civilisations are ash.

Sift directionlessly through the videotape bins at your local flea market and you will gain unquantifiable insight into the cultural underbelly of the past twenty years. There’s a unity to the VHS aesthetic which is only obvious in retrospect; a pastel dreamscape of hyper-real images, warped set design and an inexorably phantasmagoric sense of place, time and being. The only difference between recorded copies of early 90’s home improvement shows and confronting outsider art is the inexorable march of time. The faded covers and peeling plastic dust shields are part of their narratives as much as the laboured acting and piss-poor early CGI experiments. Even cheap pirate discs from nebulously located Southeast Asian narco-states don’t possess the same politico-aesthetic character. Hastily Sharpied labels – AUSTRALIA’S FUNNIEST HOME VIDEOS FINAL 1997 + ADS REMOVED – remind us not only of a time where recorded content held a permanence long since forgotten in the era of endless disk space and cheap DVR tech, but also a period of personal archival anarchy. A video cassette in the late VHS-era could contain three or four programmes on its ninety-odd minute tape length; often as truncated fragments, separated by brief walls of white noise.

Harmony Korine harnessed the caustic slow-burn of VHS’s intrinsic narrative in Trash Humpers, a clear attempt at drawing a ley-line between the dumpster aesthetic of VHS’s golden era and the butchered landscapes of the postwar American primitive. He describes the American landscape as “park garages, back alleyways, and beautiful lamp posts that light up the gutter”, a distinctively industrial vision of the nation which mirrors the film’s deliberate home video visuality. The DVD has no history as a found artefact, either in form or function. It is as it appears: clean, digital, perfect. A scratched up DVD will stop intermittently or not play at all. An old videotape, on the other hand, speaks the language of ruined junkyards and burnt-out apartment blocks. It manifest itself as the American landscape of modernity; a cataclysm of pockmarks, clustered urban forms and static explosions. A possibly apocryphal story alleges that Korine originally wanted to distribute Trash Humpers by copying it onto a tape and leaving it on a municipal bus. This would have been an entirely appropriate method for the form.

Plato, in his meditation on language Cratylus, invites us to think about hammers. A hammer, he tells us, is a hammer regardless of its material composition. A hammer is a hammer. You could build a hammer out of bamboo and the average cretin would understand what it was, even if it wouldn’t make a sturdy spice rack. Plato was wrong, of course. The Toxic Avenger is not the same film when it’s streamed on Netflix. Its ontology is different; its being is different. On VHS, it is myth – a muddy nightmare, barely comprehensible amongst the pulsing analog snow. The United Kingdom descended into moral panic in the 1980’s due to the surge of low-budget splatter flicks – video nasties – exploding onto the grubby shelves of depraved tapeslingers. These films, held together with little more than spit and prayers, were terrifying not merely because of their content, but the significance of their distribution. Can you imagine Joe D’Amato’s ANTHROPOPHAGOUS being half as existentially confronting in full, crisp high definition? A man eating his own intestines is disgusting on Blu-ray, spiritual torment on video. A hammer is not always a hammer.

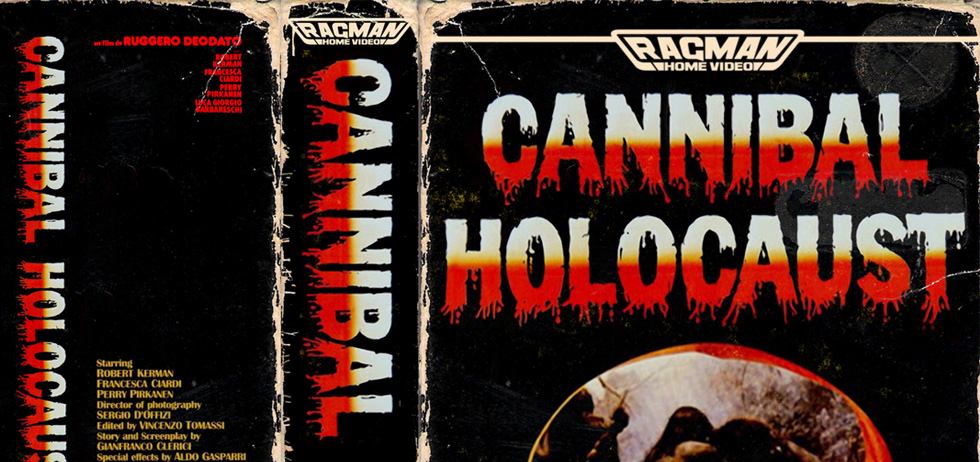

I first watched Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust as a shoddy tape-to-digital transfer, one which preserved both the natural imperfections of its original production as well as the magnetic tape sputter of its VHS distribution. I’m glad I did. The film, concerning the nakedly imperial notion of a Western documentary crew’s conflict with native cannibal tribes in the Amazon, initiated the found-footage genre with a dirty aggression that is rarely matched by today’s elaborately choreographed genre offerings. The infamous scene of the piece, in which a woman is shown impaled on a wooden pike, caused a great deal of controversy on the film’s original release thanks to the frightened general public, who believed the woman was actually murdered. Watching the movie as I did invited that same gut reaction. Of course, it was an actress suspended on a bicycle seat, but the flicker and grain of the image lent the stunt a jarring realness. Exploitation films of that era, particularly those from Europe, possessed an aura of mystery as to their origins and production. Cannibal Holocaust was never released on VHS in America, and a limited number of copies were produced by schlock-house Go Video for the UK market in 1982. It is this rarity which gives underground tapes their totemic significance.

Indeed, part of the reason videotapes have such ontological presence stems from society’s fetish for preservation. Even the most insignificant cultural objects of the 80s and 90s are still widely disseminated. The cassette represents an opportunity for a contemporary video archaeology which is tangible and physically realised. The late-night excavation of YouTube’s weirder offerings is a comparable experience which nonetheless lacks the visceral experience of an unknown videotape. The ever-popular concept of a ‘lost movie’ – etched in legend for cinephiles everywhere – capitalises on the mythology of the tape. Cronenberg knew it prematurely when he directed Videodrome, which imagines a strange, unlabeled videotape which causes brain tumours and disturbing, fleshy hallucinations in anyone who watches it. “The television screen is the retina for the mind’s eye”, the film repeats, ad nauseum.

For many years I did not know that the film I‘d inadvertently watched as a child was The Toxic Avenger. I had only vague fragments of image and sound to rely on, and I often thought that the whole event was either a dream or a false memory. Even as I watched other horror movies as I grew older, I remembered that one as much scarier, more grotesque. I eventually watched it again, on DVD, years after the fact. The film is a horror-comedy, of course, so shlock that no one but a child could ever find it scary. Watching it as an adult, in as close to high-definition as a Troma film could ever come, it lost its potency. There was a real, organic emotion to the pulsing image of the VHS. Rendered digitally, we lose some of it.

The television screen is retina for the mind’s eye, sure. Maybe the image of the mind’s eye isn’t in HD.

If after reading this you’re caught up in a VHS-induced nostalgia trip, check out the recent documentary Rewind This!, about VHS culture today and distributed by VHX. As mentioned in this piece, The Toxic Avenger (and its three sequels) are available on Netflix [US].