Here at 4:3 we don’t venture into the wonderful world of television all too often, though the relationship between cinema and television – one somewhere between bickering neighbours and friends with benefits – is a fascinating one that often does grab our attention. Madman Films is releasing Alfred Hitchcock Directs this month, a DVD compilation of all the episodes he helmed for his landmark show Alfred Hitchcock Presents (expanded to The Alfred Hitchcock Hour for the last three seasons) as well as an episode of Ford Startime, a selection which, omitting only an episode of Suspicion in 1957 (called “Four O’Clock”, which you can find online), comprises every instance of the Master of Suspense directing for the small screen. Too often considered a footnote in Hitch’s legendary career, the aim of this article is to reframe the role the show played in the evolution of Hitchcock’s own career, as artist and celebrity, pushing Hitch to new heights creatively and commercially. Through this of course we will also take a look at the episodes in the collection in terms of how Hitchcock’s style translated across to television and why this is such a valuable home video release.

Alfred Hitchcock may not have been the first household name director in history, preceded in the public imagination at least by names like Cecil B. DeMille (to say nothing of actor-directors Chaplin and Keaton) and concepts like the ‘Lubitsch Touch’ and other directors were often key in promotional materials throughout the Golden Age – directors presented as larger-than-life showmen with names above the title, on films bearing the director’s stamp and personality long before the Cahiers crew or Andrew Sarris would popularise the auteur theory. Hitchcock was, however, unquestionably the most recognisable non-performer throughout the first sixty years of cinema, and likely ever. His mere name or even silhouette evokes a brand of cinema in the reader’s mind, of countless moments and films stamped into the collective consciousness – of showers, crop dusters, birds and trains – to the extent that even concepts as cinematically quotidian as suspense, murder and voyeurism will always be linked with his films. Not to mention that many of the greatest stars ever – primarily James Stewart, Grace Kelly and Cary Grant – gave their most iconic performances in his films. With this in mind, Alfred Hitchcock Presents was a key step in the transition between beloved film director and cultural icon.

There are generally two narratives surrounding a popular filmmaker’s television work. The first is ‘their early work in television’ – directors who cut their teeth in TV, learning their craft and beginning to show their own personality and artistry in budding form through the severe limitations of the medium (budget and time constraints) before moving on to a career in film at a comparatively advanced age; exhibit A would be Robert Altman in the American cinema, as well as Michael Mann and more recently, JJ Abrams, but overseas Michael Haneke took a similar route. The other path would be much later in a director’s career – either unable to find work in film, frustrated with the industry or excited by the possibilities of the medium – with names like Steven Soderbergh and Martin Scorsese fitting the bill. While Hitchcock’s foray into television is closer to the latter (he had directed roughly 45 films when he first started Presents) what is interesting and perhaps singular is that Hitch’s tenure in television – from 1955 to 1965 – directly correlates with what is now considered his creative peak. Coming off Rear Window, Hitchcock for the next decade juggled the producing, performing and occasional directing duties of Alfred Hitchcock Presents while finding the time to churn out a few films you just might have heard of – they include Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho and The Birds.

Hitchcock was an extremely complex figure – shy and reserved, and with well-documented self-esteem issues and complexes about his appearance and particularly weight, yet he also thrust himself in the spotlight and was incredibly committed and aware about advancing his personal brand. Other legendary producer-director characters, like the outrageous popular culture impressions of Otto Preminger and Sam Goldwyn arose out of anecdotes and industry reputation (although Preminger’s rare acting roles, like a German POW camp commander in Stalag 17 or Mr Freeze in Batman definitely showed an awareness and willingness to further his reputation as a tyrannical bully) but to an extent rarely equalled even by contemporary film stars and their aggressive studio marketing, Hitchcock’s ubiquity and idiosyncrasies in his public image both at the time and what has prevailed to this day was a product of extremely calculated and marketed PR, an opportunity that only arose due to his complete power over the newly launched television show and particularly in his iconic introductions to each episode. Watching them now, they still amuse but are clearly scripted to a tee – he plays up his callous indifference and black humour in his approach to the weekly tales of murder and suspense, and quite hilariously accentuates his British demeanour – often sipping from overly ornate tea cups and drawing out and exaggerating his jowly British accent. He also continually expresses his contempt about the show’s advertisements, sarcastically telling us how thrilling the sponsors’ messages will be, making him likable to the audience but also furthering his own sarcastic, droll sensibility. With over three hundred episodes over ten years, Hitchcock the performer, narrator and creative force became a television institution, alongside other key figures in television’s early history like Lucille Ball and Milton Berle.

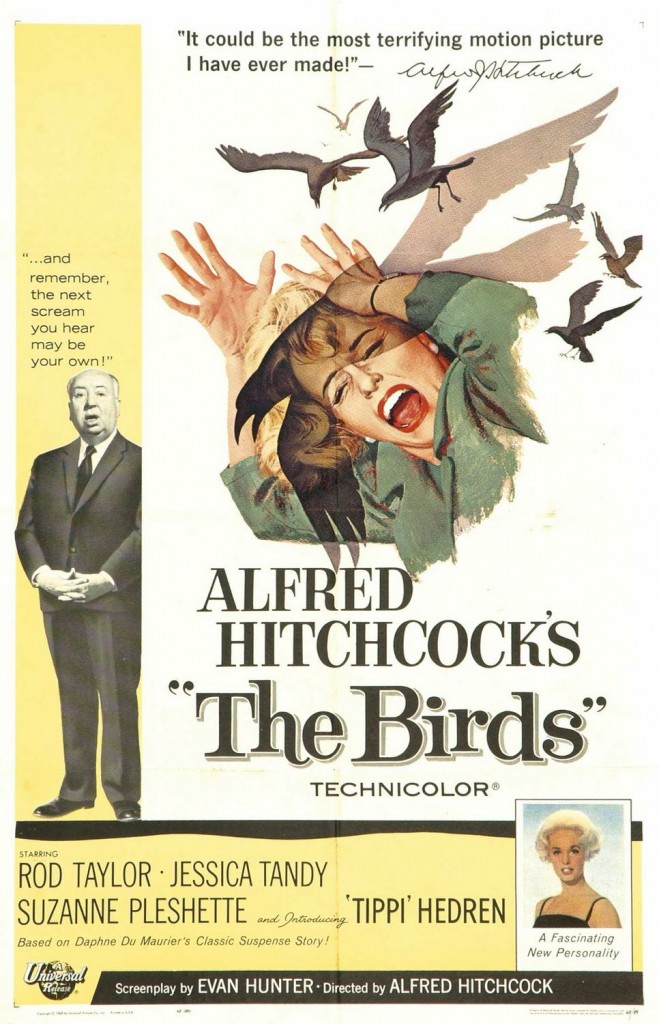

Hitchcock’s celebrity was launched into the stratosphere, to the extent where the filming of Psycho was mobbed with crowds trying to glimpse that strange man from television, and there’s the famous anecdote that some in the crowd were confused as to what the famous television presenter Alfred Hitchcock was doing on a movie set. In this same era Hitchcock lent his name to a myriad of things, including the Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine in 1956, a weekly publication of crime stories that incredibly is still producing monthly editions today, altogether making his name and image hold a monopoly over crime and suspense fiction over multiple media. The iconic profile image, made of just 13 brushstrokes (by Hitchcock himself) was instantly recognisable, alongside his famous film cameos, and it was clear Hitchcock had reached a level of fame no director had ever had, and with a corresponding style of marketing for future films – in the famous 6 minute trailer for Psycho, he walks through the sets blatantly giving plot details away with the same morbid, detached demeanour he cultivated on television, an advertising strategy that no other director would have attempted. 1 Furthermore, a cursory glance at a poster for The Birds (below) shows just how far this had reached – no less than his entire image, his signature, two quotes and his name twice (in text roughly double in size as the lead players) was used to sell the film. The image of Hitchcock would become one of the most processed ones by any celebrity, featuring on many future posters for his films, as well as turning up in places as strange as a hallway in Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) – in an industry as shallow and image-obsessed as Hollywood, the profile of a fat, bald and by no means handsome man will likely forever be considered its defining image.

So what of the episodes themselves? They clearly further what we now consider the Hitchcock style – under Hitchcock’s production company, show writers and producers were instructed to go out and find suitable scripts within particular plot parameters – more often than not, ones which built to a plot twist or shock ending. Even more so than his feature films, the majority of the television episodes (especially amongst the ones he directed) are extremely closely aligned with what we think of Hitchcock’s oeuvre – many tales of spouse murder, of dramatic irony and some killer segments of great tension. The very first episode, starring Vera Miles (on the path to stardom with Hitchcock, between this and The Wrong Man, and slated for the lead in Vertigo before committing that most cardinal of sins for an actress – falling pregnant) features some wonderful, unbroken scenes showcasing the his mastery; a long scene where a husband finds something wrong upon returning home and before checking on his wife has to take something burning out of the oven, or an extended sequence in a hotel corridor stalking his wife’s apparent assailant, with the eventual climactic action only seen by shadows on the wall – technically great filmmaking runs through all these episodes, with a level of craftsmanship rarely seen in the medium’s early history.

To varying degrees, episodes in the set strongly evoke some of his classic films. ‘Mr Blanchard’s Secret’ about a neighbour suspecting the man next door has killed his wife clearly sprouts from Rear Window and both ‘The Perfect Crime’ and ‘Wet Saturday’ have killers standing around talking about making a perfect murder that’s very reminiscent of his 1948 classic Rope. This comes across less as any sort of self-parody than a mix of further carving out Hitchcock’s own niche of pictures – of middle class, proper (a surprising amount of which are British, or British expats) protagonists in impossibly suspenseful tales – mixed with a healthy attitude of “give ‘em what they want”, and for the Hitchcock fan, the show delivers that in dollops. There are occasional excursions out of this domain such as the quite wonderful “The Curse of Mr. Pelham” featuring Tom Ewell and his doppelgänger, which in its foray into the supernatural would look more at home in The Twilight Zone – a show the episode precedes – but is crafted into an incredible half hour of television.

The influence does go both ways, however, and their ideas, modes of filmmaking and entire set pieces that will be lifted out of episodes to make future classic scenes in his films. His most successful film is probably still Psycho (well, it’s the first result under his IMDB listing) and this is the film that most clearly springs from his work from the show. Working with the freedom the constraints of television could afford, he made Psycho quickly and cheaply by using the same crew as the show, and reverting back to black-and-white for the first time since The Wrong Man in 1956. With a budget of merely $800,000 (his previous film, North by Northwest, was more than five times that) he had an unusual amount of artistic control, allowing him to experiment in ways that changed film history – infamously killing off a protagonist that early in a film, and having the audience identify with a killer through the power of perspective and better, suspense. One of the absolute best episodes in the set, “One More Mile To Go” anticipates a lot of this – in a masterful, wordless opening, we peer into a couple’s living room from outside (Hitchcock voyeurism at its finest) and we don’t hear but we see an argument brewing, escalating into the husband murdering his wife. The rest of the episode is the husband, with the corpse of his wife in the boot of the car, driving around trying to dump it somewhere, pursued doggedly by a policeman – unawares, but taking an interest in the killer’s broken taillight. The suspense is absolutely nail-biting, and through mastery of form we can’t help but sympathise with the killer and want him to go unnoticed – a sentiment very similar to that towards Norman Bates in Psycho’s incredible scene where the car holding Marion Crane’s corpse slowly submerges into a swamp.

So these episodes Hitchcock directed in many ways are a valuable cultural document as practice grounds for experiments in storytelling and filmmaking, but rather than merely curios they more often than not work on their own merit. One of the absolute gems of this set is Hitchcock’s only ever colour television episode, “An Incident at the Corner” from the television anthology series Ford Startime (the name of which is a wonderful reminder of television’s commercial beginnings and brand dominated viewing, like how Martin & Lewis found stardom on the Colgate Comedy Hour) that at an hour long, almost qualifies as a forgotten Hitchcock film, and has Hitchcock at his most experimental, shot a week after Psycho with the same crew (as well as Vera Miles once more). The ‘incident’ in question is a mere traffic violation outside a school that has ramifications for much of the small-knit community. Shockingly, the episode starts with the incident shown from three separate angles, each revealing more information than the last –so brilliantly handled that you believe he’s cheating – in the last angle, there’s a crucial car in the middle of the frame that seemingly didn’t exist in the first two, until you rewind and see it carefully obstructed from our view by a traffic sign. It’s a scene that anticipates DVD culture, of pausing and rewinding at will, ironically in an era and medium where the expectation (for a show like Ford Startime) was that the episode likely would never see the air again. It also precedes a film like Blowup or The Conversation – testing exactly what we see and hear (a crucial word is misheard).

The narrative itself is also an interesting piece, clearly moralistic about the dangers of gossip and of rumours causing irreparable harm to families and communities, established with an opening montage of close-ups of mouths whispering into ears, and seemingly a vicious statement to small town America still coming to terms with the repercussions of McCarthyism. It’s not completely successful, with plenty of speeches about integrity (not through lack of trying, George Peppard doesn’t quite convince with morally indignant dialogue that only Jimmy Stewart could pull off in earnest) but it’s a pretty fascinating piece of television, even for strange moments like Hitchcock shooting a dialogue scene from a ceiling angle – whether it’s a comment on neighbourly surveillance or trying what he wanted because he could (it comes across as the latter) – it’s a canvas where one of the medium’s most influential artists is trying out new strokes. Kudos to Madman for digging up this fascinating gem for inclusion in the set.

So ultimately, are Hitchcock’s television episodes successful? In short, yes. They occasionally suffer from the abbreviated length of a television episode (some are really big on talk and exposition), and occasionally miss the subtext that his richer films have – at least for me, the psychosexual subtext like Stewart’s impotence and voyeurism in Rear Window, the romantic obsession underpinning Vertigo and whatever the hell the Freudian overload in The Birds amounts to are such powerful narrative undercurrents that they produce a near visceral reaction, and the episodes obviously don’t aspire to that calibre. They are however, clearly the product of and instrumental to the development of one of the most legendary careers in in cinema – as a cultural document, they’re essential to understanding Hitchcock as popular icon, and for entertainment value can’t be beaten (I haven’t even mentioned some of the best episodes on offer, like the Roald Dahl scripted “Lambs to the Slaughter”), and Madman have done a great service in bringing all the episodes in one set. One criticism of these episodes I will dispute however is that against his infamous closing remarks – again and again in the show, the episode will end rather ambiguously or bleakly, where a killer will get off scot-free, before Hitchcock’s closing monologue will give us more facts telling us that after the episodes’ conclusion, further events happened that did ensure justice and morality was served – it will strike as odd to the modern viewer, but I don’t think it’s as simple as tacking on a happy ending. Rather, Hitchcock knew that the audience trusts what we see, not what we hear – when we see a murderer get away with it, we take Hitch’s verbal appendix with a grain of salt. Hitchcock understood viewer psychology better than any other filmmaker, and because of this his tricks and ploys with the spectator still resonate fifty years later.