In this second dispatch from the 2014 New York Film Festival, a look at three biopics of very different temperaments, new documentaries from two of the genre’s masters, and a film from Africa that humanizes the headlines.

Let’s just get this out of the way first, shall we: for all the endless talk of the Bat-member’s appearance in Gone Girl, it’s not even close to the program’s best male nudity. That distinction would belong to Saint Laurent, whose star Gaspard Ulliel is in possession of arguably the festival’s penis du jour; and there’s even a little Louis Garrel on display, for those so inclined. Bertrand Bonello’s biopic of the Gallic fashion design icon—the second such this year—contains many other delights, too, though its audio-visual richness and self-conscious chronology shuffling belie a rather pedestrian take on a colorful life.

Rather than attempt a career-spanning overview, House of Pleasures director Bonello smartly opts for exploring a period of Yves Saint Laurent’s life—roughly the mid-’60s through his feted Spring ’76 show—restricting his focus to the younger man (Ulliel), his grappling with potentially destructive fame, and his two great loves (tenderly portrayed by Garrel and Jérémie Renier.) Aesthetically, its intoxicating stuff: Bonello’s vivid attention to period detail, his recreations of Saint Laurent’s lurid personal life, and the evocative, Tangerine Dream-esque score are immersive, and the film’s narrative leaps into the future—with Helmet Berger as the elderly YSL—convey an atmosphere of a legend hermetically sealed by his own brand. Like too many a biopic, however, the subject himself proves elusive, and much of the formal gymnastics seem designed to compensate for this shortcoming. Still, that may be the point: “We are bodies without souls,” we see Saint Laurent writing in one scene. “Because the soul is elsewhere.”

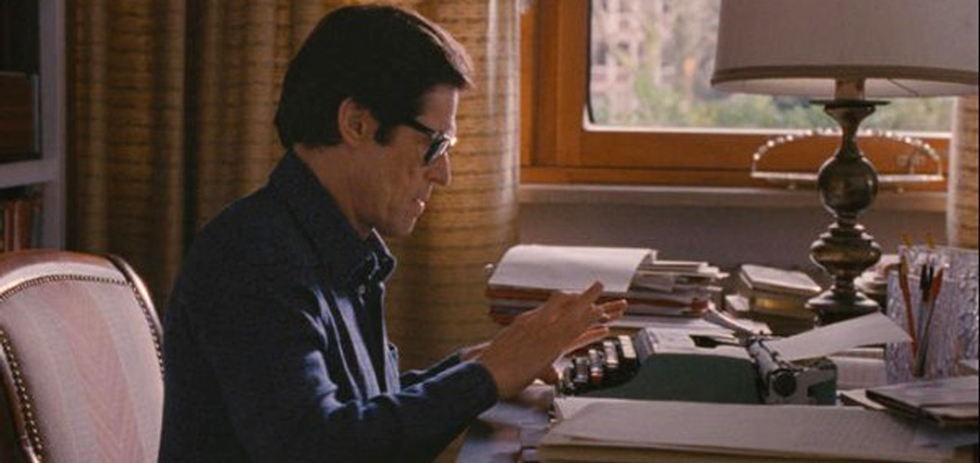

If the eponymous maestro in Pasolini proves similarly hard to get a handle on, then it’s very much according its filmmaker’s design. Abel Ferrara’s passion project settles in for a look at just the last few days in the life of the Italian director, poet, novelist and all‐around genius, beginning as he gives an interview while editing Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom and ending with his tragic – and to‐date, never solved – murder in 1975.

Barring some closing conjecture, the why of Pasolini’s death isn’t on Ferrara’s mind, which will frustrate those who like their biopics to play detective. Instead, the film serves as an affectionate tribute from one filmmaker to another, with Ferrara and Willem Dafoe – who captures the essence of the man, despite the physical difference – engaging artistically with their hero on intimate terms. Ferrara’s own Italian‐Catholic background and history of filmic controversy make him well matched with his muse, and the movie’s best and boldest sequences – imaginings of Pasolini’s unfinished script for Porno Teo-Kolossal, featuring Ninetto Davoli – go a ways to locating the intersection of both men’s sensibility.1 If Pasolini finally raises more questions than it answers, then all the better.

Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner, meanwhile, takes a far more conventional approach to its subject – which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, particularly with a central performance that’s so vigorous. An accessible, crowd-pleasing look at the personal and professional travails of the 19th century landscape painter, the movie affords Timothy Spall a rare leading role outside his gallery of supporting grotesques, even if the veteran actor’s performance essentially amounts to more of his usual antics – and enough comedic grunts to take Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino title. Split between the artist’s celebrated landscape work and his more base pursuits, Leigh’s film balances historical detail with interpersonal curiosity and generous helpings of humour – often at the expense of art critics (Joshua McGuire’s ludicrous take on John Ruskin is a treat.) The Turner‐inspired Impressionist cinematography, by longtime Leigh collaborator Dick Pope, is of particular note, and possibly the strongest element in a film that sometimes feels like merely a vehicle for a big, awards-season performance.

Turner may well have appreciated the utopian world of Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery, an inclusive three-hour documentary tour of London’s prime art institution that’s right up there with the veteran filmmaker’s best work (which is saying a lot.) Opening on a montage of gallery pieces before wryly segueing to a shot of a lone cleaner vacuuming the floor, Wiseman’s inquisitive camera moves across visitors, curators, academics and behind-the-scenes restoration to create a masterly tableau of art and the many ways in which it’s perceived, maintaining a consistently engaging dialogue between viewer and film in the process. It’s a testament to the filmmaker’s peerless control of the form that none of National Gallery’s 180 minutes feels inessential; by the time Wiseman arrives at his final, gracefully staged shot, the effect is entirely enchanting.2

At 84, Wiseman is a kid relative to 90-year‐old Iris Apfel, her 100-year-old husband and 87-year-old director Albert Maysles, the trio who form the wizened nexus of the legendary documentarian’s new film. Named for its star – the lifelong clothing and accessory icon, celebrated designer, and “rare bird of fashion” – Iris is a vivacious snapshot of an elderly It Girl who has retained all the passion, curiosity and inventiveness of youth. Embodying eccentricity before it became a branding concept, Apfel’s style is a personally curated meeting of high fashion, junk store eclecticism and interior design, and Maysles’ loving portrait sometimes echoes the blissful madness of the Beales in his Grey Gardens.

While it’s easy to mistake Iris as an amiable, slight piece, dig deeper and there’s a whole cultural history beneath the surface – often reflected in Apfel’s sheer longevity – while her exuberance is astonishing.3 The film’s playfulness, shot by Listen Up Philip DP Sean Price Williams, allows Maysles to unobtrusively comment on almost a century’s worth of art and fashion, with a refreshing lack of elitism that mirrors Apfel’s own. “You don’t own anything when you’re here,” she reflects, refreshingly for a woman who’s hoarded a lifetime of accoutrements. “You really just rent.”

Similarly audience pleasing – almost to a fault – is Gabe Polsky’s documentary Red Army, which depicts the Soviet Union’s superstar ice hockey team of the 1980s and the players’ will-they-or‐won’t‐they dances to defect to the West. Confidently (and obviously) setting up his subjects as contemporary parallels to the twilight years of the Cold War, Polsky combines well-edited archival footage and recent interviews with players who talk of their love of the sport versus their tussle with the State’s authority. The star among them is former defense hero (and later, Minister for Sport) Slava Fetisov, who is both candid and cheekily resistant to his director’s more baiting questions. Like a good sports film it’ll hit all the right notes for its intended market – and leave others eventually disinterested.

Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu is something of an anomaly, at least with respect to Western cinema, in that it successfully approaches a politically- charged scenario with humanity and humour. Tensions run high when fundamental Islamists overpower a local village and administer a crackdown: women are ordered to cover up, music and sport are banned, and the residents fall under the merciless eye of gun-toting militants who aren’t afraid – in one of the movie’s opening, and best, shots – to blast away at traditional African masks like they’re cans on a fence.4

It’s a movie about the strength of a community’s resistance, and in particular the resilience of its women: from a local trader who defiantly refuses to wear gloves, to a women who continues singing while being lashed, to a Haitian witch who openly mocks the oppressors, the film gives voice to a minority not often considered in the jihad debate. Sissako’s ability to illustrate these things at a very human level, removed from the typical political sloganeering and rhetoric, imbues Timbuktu with a power that speaks beyond the didactic. At the same time, he’s careful not to demonize the fundamentalists, offering them as hypocritical but flawed individuals often uncertain of their actions (a bungled recording of a video threat amusingly reminds of Chris Morris’ Four Lions.) Easy answers aren’t proffered, nor are they Sissako’s mandate; an incredible final shot speaks more volumes as to the delicate mingling of his narrative’s hope and despair.

Adapting Georges Simenon’s novel, actor‐director Mathieu Amalric’s The Blue Room continues the recent trend toward boxy, Academy ratio framing for this story of an affair gone awry. Amalric plays a man who escapes a sterile marriage to a passionate rendezvous with an old flame (imposing co-writer Stéphanie Cléau), only to find himself – and his movie’s narrative – splintered with treacherous intent. Cut between flashbacks to the affair and scenes with Amalric’s character incarcerated and awaiting trial, The Blue Room effectively winds up an atmosphere of claustrophobia and red-herring deceit, assisted nicely by the director’s use of the frame to push his characters off center and into uncomfortable traps.5 The film’s judicial withholding of information might be a stalling tactic for what is ultimately a pretty lackluster resolution, but the getting there is a tense enough journey.