Brian Knappenberger’s documentary The Internet’s Own Boy offers an engaging portrait of online activist Aaron Swartz, focusing on his transition from programmer to political hacktivist. The events depicted make this documentary first and foremost a frustrating one, with the series of injustices imposed upon Aaron only heightened by moments of heartfelt and intimate reflection on his intertwined personal and political life.

In the opening of his film, Knappenberger compiles intimate home videos of Aaron and his family from a young age. This works to both develop Aaron’s character from childhood and inform the audience of his early intelligence. The use of home video lends justification to Aaron’s purported computer intelligence and his personal characteristics as a carer and teacher. Knappenberger builds on Aaron’s relationship with computers at an early age, fluctuating between the intimate voiceover provided by his family, and the use of talking head interviews which act to further enhance the intimacy we develop with him.

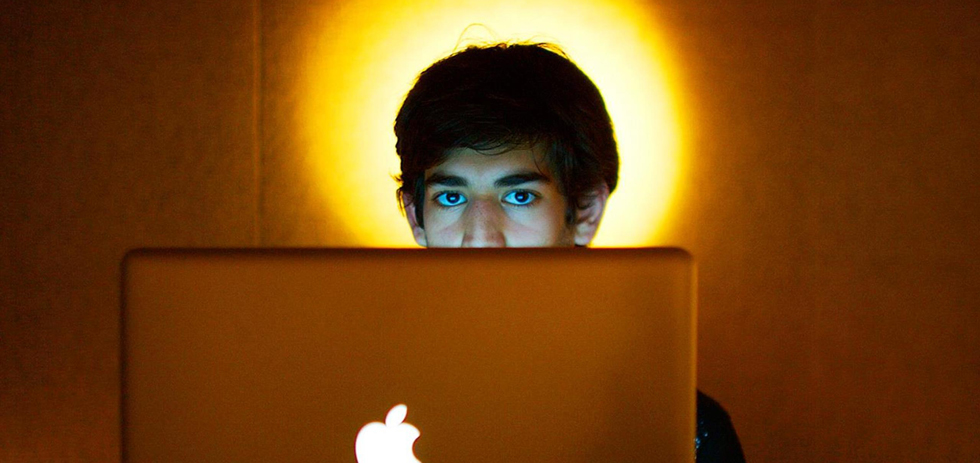

Moments with those closest to Aaron, his brothers especially, build on the film’s warm and intimate tone, and challenge a general perception of an internet figure, so easily perceived of as distant, cold and detached. These humorous moments with his family contribute to a portrait of Aaron as being endearing as well as intellectual, propelling his general optimism and political mindedness to invoke justice for the greater good.

Knappenberger uses interview subjects particularly well. These subjects are positioned to coincide with the timing of Aaron’s own personal development, and introduce the audience not only to Aaron’s family but also to a number of Aaron’s political motivators, including Tim Berners-Lee (inventor of the World Wide Web). These professionally informed subjects reinforce Aaron’s position on public access, arguing that the internet should remain as a highly decentralised network, rejecting any notion of placing power through a centralised network capitalised on by large corporations. As this information is disclosed to the audience, the stylistic interludes of computer screens clicking and disclosing screen-shotted information correspond to the audience’s own sense of investigation. Knappenberger places the viewer as if they too were hacking and gaining insight into broader, undisclosed ideas that Aaron personally narrates to us using home video over the course of the documentary.

This documentary comes at a pertinent time where the process of creating laws surrounding computer misuse and the policing the Internet is very much underway. The film’s ending is particularly instrumental in conveying this idea. Knappenberger dedicates a comparatively small fraction of the film at the end to revealing Aaron’s suicide. Knappenberger thereby focuses the majority of the film on revealing his hard work and influence, while creating a sense of the continuous change that can be enacted through online activism. There is never a sense of Aaron being gone, rather leaving behind a continuing legacy dedicated to fighting injustices surrounding digital censorship.

The Internet’s Own Boy raises a number of issues only to be developed and expanded on over time. The use of talking head interviews outlines a variety of unified opinions that work to build a portrait of Aaron as well as acting as a platform to discuss the freedom of the internet. In particular, notions of copyright and of public access to open online libraries form the main motivators propelling Aaron’s transition from programmer to activist over the course of the documentary. This technique also ensures that the issues disclosed are made easily understandable, given they’re explored thoroughly, personably and justifiably. Most importantly, this seems to exemplify what Aaron would have wanted regarding free access to information for the benefit of the general public.