You Have to See… is a weekly feature here at 4:3, where one staff writer picks a film they love and makes a group of other writers watch it for the first time. Once this group has seen the film, the suggestor writes a piece advocating the film and the others respond below. Whilst not explicitly spoiling the film, the article is detailed. We would recommend seeking out and watching the film each week, then joining in the debate in the comments section.

This week Jeremy Elphick looks at Nagisa Oshima’s 1971 film The Ceremony (Gishiki).

Nagisa Oshima stands as one of the most challenging, relevant and subversive presences in Japanese cinema with a body of work that matches his importance as an individual. Shohei Imamura, arguably Oshima’s closest contemporary within the popular sphere of Japanese New Wave, most famously compared himself to the director in a statement that starkly distinguished each filmmaker’s approach to cinema, simply stating: “I am a country farmer, Oshima is a samurai.” For Imamura, cinema was about existential ennui, concerning itself with reaching for a deeper understanding of metaphysical ideas of self, truth and meaning in an often reflective and subtle sense. Oshima’s output is historically contextualised as that of a radical at the forefront of the New Wave movement – a great deal of his films are highly political, aggressively left-wing statements against authority, and deeply engaged with the movement he spearheaded with his contemporaries. In what could be his most famous quote, Oshima’s revolutionary attitude to cinema in Japan is clear (specifically towards the generation of filmmakers he was succeeding): “My hatred for Japanese cinema includes all of it…. I’m not attempting to remain within this congenial, older mode.” Oshima’s work reflects what Isolde Standish views as the key tenets of the overtly transgressive Japanese New Wave. Sex and crime are dominant, the independent woman re-emerges in a cinematic context, the male body is commodified and displayed in a re-negotiation of the place of women within the political economy of masculine exchange, and often systems of patriarchal exchange are portrayed in an urge to highlight their flaws and call for their insurrection. For Oshima, Ozu’s harmonious image of Japan is not simply idyllic; it is false. The Ceremony (Gishiki), is one of the director’s most comprehensive statements. It doesn’t share the controversy of In the Realm of the Senses, the popularity of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence or the cult status of Night and Fog in Japan. It is, however, arguably the director’s strongest work.

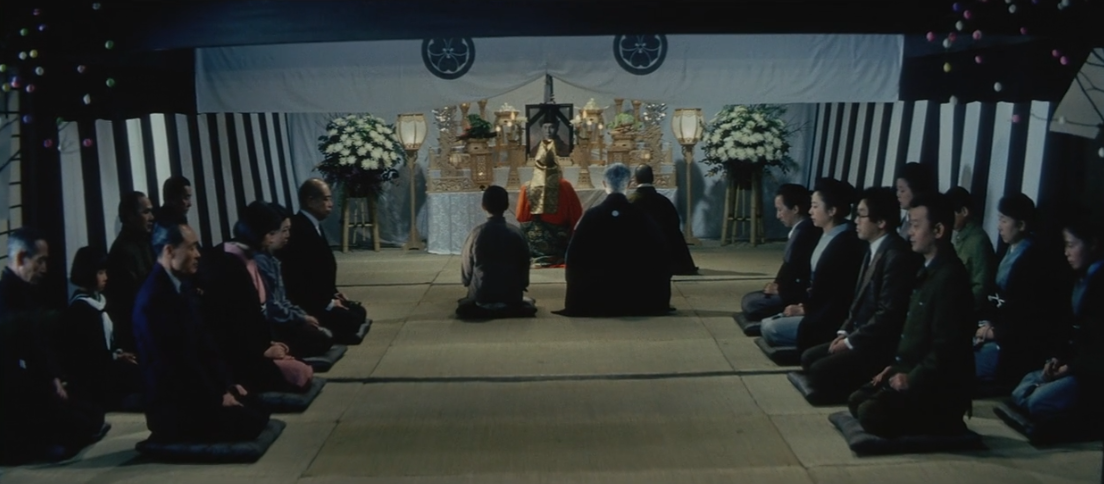

Oshima’s film doesn’t revolve around one ceremony, but instead concerns itself with two key types: weddings and funerals. Structurally, the film isn’t dissimilar to an Ozu work: long takes, focusing on a long-held tradition, with its keenest eye drawn towards interactions between a traditional Japanese family. The brilliance of The Ceremony lies in Oshima’s cinematic transgression; he employs a form of cinema used by his predecessors and inverts it, revealing a far more conflicted, flawed and existentially tormented Japanese consciousness. As Donald Richie highlights, these ceremonies aren’t celebrations or periods of growth as they were often framed in pre-1960s cinema in Japan. Each ceremony is instead “carefully timed to coincide with a year significant in the postwar history of Japan. Each marks a stage of a downward spiral, for it is the ‘spiritual death’ of Japan that Oshima is chronicling.”

The Ceremony often flirts with presenting itself as a ruthless parody of the family saga. The Sakurada clan’s collapse, their familial conflict and their slow decay mirrors Japan’s post-war fall from grace. It is enamoured by Oshima’s growth as a filmmaker, with his radicalism becoming more nuanced and targeted rather than simply functioning as rebellion. At its core, the film comments on the shifts in Japan’s post-war trajectory. The Ceremony is a highly political film, and Oshima is a political filmmaker, in The Ceremony he feels at home as he navigates the situations, policies and state of Japan society. The film follows an initially simple concept of the Sakurada clan and their various ceremonies, where each marks a further descent into a fever dream of uncertainty and decay, serving as a stark critique of Japanese cinema’s self-perpetuated image of stability and calm that Oshima grew increasingly incensed by.

The Ceremony is arguably Oshima’s strongest film due to its immense scope. While it isn’t his longest film, it remains his most ambitious, recounting decades, presenting a broad family as an allegorical representation of a broader trend within Japanese society, and furthering his own cinematic philosophies of sex, transgression, decay, and political inadequacy. In his focus on “special” ceremonies, Oshima normalised them and removed the sanctity they held within his presentation of Japan. They are no longer rare events, but a ridiculous status quo punctuated by tension, human failing and a gross social and political decay. Oshima revealed, when discussing the film, that ceremonies are a time when “the special characteristics of the Japanese spirit are revealed.” He continued “it is this spirit that concerns and worries me.” In the film, this spirit is portrayed as everything from imperfect to chaotic and in his depiction of the Sakurada clan he tears at Japan’s self-image.

The Sakurada clan is rigid, patriarchal and highly militaristic. It resonates with the conservative, right-wing and ruthlessly nationalistic Japan – something more in line with what Yukio Mishima envisioned. Yet this is where Oshima’s strength is clear. He begins with this idealisation, not too distant from how a Japanese family drama would begin. From here the process of destabilisation is never overt; it creeps into the film, moving into the way the clan interacts, how their ceremonies function, and positioning the viewer in a place of uncertainty towards how long the Clan’s ceremonies can maintain their coherency before the layers of the multi-faceted chaotic fever dream wash over and consume the film’s initial stability. The film is by all accounts a melodrama. The protagonist (Masuo) cannot escape the ritualistic and self-perpetuating nature of the clan he is a part and is initially framed at the centre of the film. That said, Oshima has no intention for the concept of “the centre” to remain relevant to his film as he drives it into an increasingly absurdist state, while maintaining the clarity of his criticism.

Masuo is a Manchurian repatriate and the heir to the clan. He comes of age in the film, his grandfather leading a ceremony that positions the film in a place of instability and disintegration. Masuo’s wedding is without a bride, yet it occurs nonetheless, as empty as any of the ceremonies that punctuate Oshima’s film. Routine becomes excess and in both ceremonies in the present (as well as flashbacks and time warps to past rituals) the reverence with which the acts presented were held in Japanese society is mocked as farcical. At the heart of The Ceremony is this constant prodding at the established values of the time, attempting to collapse them completely by the film’s conclusion. His subjects are not by any measure inhuman, however, as their consistent relatability – in their neuroticism, their fears, their passions, their anger, their sadness – positions an increasingly uncomfortable audience as their own conceptions are positioned as farce. Oshima’s piece doesn’t simply function as a social critique of Japanese values, it simultaneously makes harsh statements about human relationships, and his uncompromising approach to such presentations is what make The Ceremony such an affecting piece to experience: it is at once accessible before alienating the drawn-in and relating audience.

The Ceremony isn’t simply one of Oshima’s strongest works, it’s one that simultaneously acts as summation of his earlier – often lesser seen – films. He reengages in what Nelson Kim of Senses of Cinema terms the “Brechtian anti-realism”. The same anti-realism that permeated Death by Hanging in his marriage to the bride without the bride. This crushing claustrophobia, the denied possibility of personal freedom and the intense neurotic habit coupled with a psychoanalytic sphere as Masuo returns to his childhood as retreating from his conscious state. These compulsions are often exhibited by the older figures in the film, asserting their last control and dominance of their world over the malleable and weak Masuo and his contemporaries. In this presentation, Oshima rejects the past with a virulent dismissal of it in its entirety, while mocking his own generation’s apathy. He exhibits it as weakness, continuing his cinematic trend of subversion and transgression in a way that utilises his art to make lasting statements on the human psyche.

The Ceremony leans towards satire at times, more serious critique at others. Sometimes the film is a drama, sometimes it feels altogether undefinable. What we have in Oshima’s film is a rare and wholesome cinematic statement that rejects the constraints of genre and form, that subverts perception as much as Japanese cinema. It’s relentlessly critical – of the right, of the left, of tradition, of the present – and radical in its approach to filmmaking. It takes as many hints from Ozu as it takes from Godard and presents itself as a substantively inspired film. It doesn’t feel Japanese, but it doesn’t feel European, it feels like a movie by Nagisa Oshima. It’s this distinctive approach to cinema, art and politics and the director’s ability to truly realise them to such a cohesive degree that makes The Ceremony a film you have to see. Viewing the film within the context of 1970s Japan positions it as a remarkably transgressive and rebellious piece. While Japan has moved away from this period of existential crisis on a national scale, much of the film’s criticisms are stark as ever – as Ozu, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi and other ‘classic’ Japanese directors resurface for their cinematic approach, it is only fair that Nagisa Oshima resurfaces for his painstakingly justified opposition to it.

On a technical level, Oshima’s film is beautiful, shot with precision, composed with the eye of a true aesthetic master and arranged with intricate care in a way that concerns itself with politics and philosophy over simple visual beauty (while nonetheless achieving the latter). Toru Takemitsu’s score matches the film in its breadth and lasting impression. From Teshigahara, Kobayashi, Shinoda, Imamura to Kurosawa…to Oshima, Takemitsu’s scores were the most daring and challenging within the Japanese cinematic sphere in the 60s and 70s. Takemitsu’s score frames the film with a disorienting modernist approach that sits alongside in careful and subtle opposition to the traditional Japan that Oshima portrays.

The Ceremony is a stark critic of a countrie’s values, its cinema, its history, and its present. It is uncompromising and brutal in its portrayal of Japan, but it is lasting. Its criticisms are broad rather than specific and it never falls prey to triviality. Oshima’s technique and philosophy towards filmmaking permeate the film, and what emerges is a deeply important film that is able to egress from its original context as a perpetually relevant critique of a potential manifestation of any society. In The Ceremony, Oshima not only gives a cinematic summation of his early work as a filmmaker, he breaks from it at the same time, and he creates one of his strongest films in the process (if not his strongest). An essay isn’t able to do it the justice it deserves – rather, you have to see The Ceremony.

Responses

Mei Chew: The Ceremony, one of my favourite Oshima films, is an especially interesting exemplar of his work because it most clearly and overtly reifies his concern with the dynamics of influence between human beings and the architectural spaces they inhabit and create. In The Ceremony, Oshima hyperbolically aestheticises the politics of spatial and visual rhythm developed in his earlier film, The Man Who Left His Will on Film (Tokyo Senso Sengo Hiwa), made the year earlier. As a result, the film takes on an atmosphere of theatricality that extends to its structure, which emulates a ceremonial unfurling of set pieces, alternating between internal, past spaces and external, present and possible future spaces. Through this interlacing construction, Oshima places the coinciding pressures within postwar Japanese society at a non-localised point of tension between history and its inevitable expiration and succession with the passing of time. The possible form civilisation might take in a Japan at the cusp between empire and modernity is complicated by its genesis in the destructive rupture caused by the effects of the atomic bomb and WWII, which are paradoxically also radically regenerative. In the interim, the ceremonies sustaining once esteemed values of patriarchy and familial hierarchy are caught between irrelevance and absurdity; so Masuo must endure the empty spectacle of a wedding without a bride.

The Ceremony alternately inhabits the interior rooms of the archaic Sakurada residence, where human behaviours conform to the building’s closed and shadowed anatomy; and the kinetic, transient space of the train cabin Masuo and Ritsuko occupy as they travel to Terumichi’s cabin. Oshima’s representation of the competing desires for permanence and transformative movement that possess both human beings and the architectural environments they create seems to imply a claustrophobic suffocation caused by insularity. However, The Ceremony progressively presents the conflation of past and future, internal and external spaces, (for example as adults Masuo and Ritsuko recreate ceremonial codes within the Sakurada residence, while oblique visions of a buried infant abandoned in Manchuria are conjured imaginatively into their present-day memories) creating a permeable film forming the textual substance of The Ceremony. In its conclusion, The Ceremony finally provides a chronological and geographic heterotopia, a final eruption which multiply opens the film as a magnificently surreal succession of thresholds of physical realities and human flesh.

Jake Moody: The only other Oshima films I had seen before The Ceremony were his embryonic New Wave crime thriller Cruel Story of Youth (1960), and the much-feted In the Realm of the Senses (1976). This film, produced between the two, feels very like an agglomeration of the rebellious youthful radicalism of the Sun Tribe films, and the transgressive sexual politics of the later film (which – full disclosure – I hated). Here, though, Oshima, in drawing on both the intimacy of familial drama and the tragic spectacle of a nation in crisis, for my money, makes one of the most successful attempts at confronting Japan’s post-war social malaise I’ve seen. Jeremy’s description of the ceremonies that define the film as exercises in “ridiculous status quo punctuated by tension, human failing and gross social and political decay” struck me as a great crystallisation of what makes The Ceremony tick: the way that Masuo and his cousins are clearly irreparably damaged by these occasions of forced dignity, but at the same time seemingly held together by the image/notion of a family unit is uncomfortably close to the mindset of the Japanese nation in defeat. Interesting, then, that the Oshima quote Jeremy uses is also about that kind of tension or cognitive dissonance; as he says, these formal ceremonies contain the “special characteristics” of the Japanese psyche, but are as a result the most concerning parts of it.

There are some other stylistic aspects of the various funerals and memorials, and the flashback structure, which I think add to that same sense of incongruity. Temporally, the use of Masuo as a kind of unreliable narrator also evokes the many half-truths and loaded tales of political reality; it’s telling that the idyllic baseball game he recalls at the end of the film has previously been called into question, Ritsuko insisting that he is wilfully misremembering who was present and what took place. Jeremy’s idea that the viewer is forced into a “place of uncertainty towards how long the clan’s ceremonies can maintain their coherency before [they] consume the film’s initial stability” pretty much sums up this process. The way Oshima enacts this uncertainty, though, is incredible – I was particularly struck by the grandfather figure, whose role as a cipher for political traditionalists aside, is a terrifying and almost ethereal figure. Played by Kei Satô, who at 43 was about the same age as the actors playing his sons, Kazuomi Sakurada has an inhuman air about him, with unnaturally silver hair, robotic movements and an implacable coldness. His characterization captures both the allure and the terror of the Japanese establishment. Finally, the room in Kazuomi’s home where all but one (the wedding that isn’t) of the ceremonies takes place is similarly discomfiting. A blank, monochromatic space, it’s unlike any room I’ve ever seen, especially in an otherwise largely realist film in terms of setting. It becomes more and more striking to see the younger generations of Sakuradas return to the room over years, as they modernize and age, and this creepy atavistic space does not. While I’m usually a sucker for filmmakers who sit at the unloved fringes of more broadly respected movements (Jacques Rivette, Ermanno Olmi, Nelson Pereira dos Santos), Oshima never seemed as literate or introspective a filmmaker. Having seen The Ceremony I definitely understand the hype.

Jess Ellicott: I’d only seen In the Realm of the Senses, so it was interesting to see how radically different this was in approach, while still holding several seeds of ideas Oshima would later explore in that film. (For example Uncle Mamoru’s drinking song references the subject of Senses, Sada Abe, so it’s clear she’d been a long-standing fascination of his.) I think it’s more radical and subversive than In the Realm of the Senses in formal terms, with a freeform pastiche of traditional melodrama, modernist fragmented narrative and Freudian psychosexual elements that reminded me strongly of Godard. It’s astounding how Oshima pulls off this balancing act of subject, form and tone, forging incoherence into cohesion. Jake said that the film is “largely realist” in terms of setting, but to me it’s a high-art dream world from start to finish. It’s an incredibly beautiful film as well, which the copy I saw really didn’t do justice to. I’d probably skip my own wedding to see it on 35mm.