A 61-minute experimental feature that keenly focuses on the intersection of place and time, Ion de Sosa’s Sueñan los Androides (trans. Androids Dreams) is a unique hodge-podge of ideas and imagery that’s as much about its setting as the action within. The selling point for the film, at least the way it seems to have been pitched at the Berlinale, is in its relationship to one of the most influential science fiction films ever, Blade Runner.1 Framed as a hyper-minimalist reinterpretation of that film, it actually lifts its title and many thematic and plot elements from the Phillip K. Dick novel that inspired Ridley Scott’s film, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

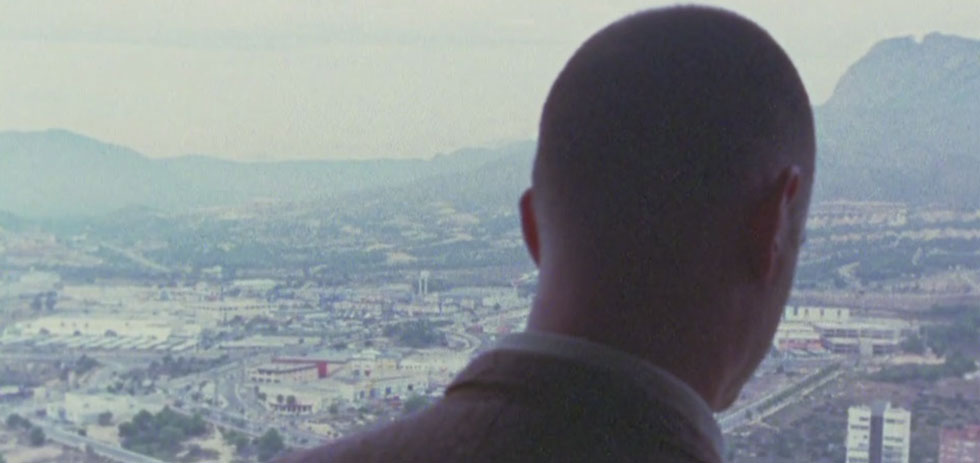

The first thing we see is a wide shot encompassing the seaside Spanish city of Benidorm, an amusing nod to the shot of Los Angeles that opens Blade Runner, though where that film begins with soaring flames, Vangelis’ synth-laden score and a quick shot of a Replicant’s eye, de Sosa holds on Benidorm, the jitters of the film itself and the wind the only accompaniments. Yellow text appears on-screen, telling us this is Earth in 2052 (mirroring Blade Runner‘s 37-year-gap between film setting and release date), though the only sign of the future is mass abandonment; there’s less traffic, the buildings seem like perfectly preserved ruins of modern culture, de Sosa emulating much of the minimalist sci-fi setting in Alphaville, though, unlike Godard, he rejects all overt physical elements of futurism.2 Of course, in achieving this effect the city has been shot in the off-season, less Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later than Yorgos Lanthimos’ Kinetta in its sense of emptied location, and de Sosa makes the most of it by spending the first few minutes of the film cutting between shots of empty buildings, hallways and rooms.

His background as a cinematographer is felt throughout, the imagery surpasses any thematic content; he finds beauty in symmetry, positioning completely gutted apartments as sleek and clean remnants of life, reminiscent of Benning and Seidl. As becomes apparent later, the camera acts as a clinical eye, almost machinistic in its cataloguing of windows and spaces, both in framing and in the rhythmic nature of editing, carefully ordered and aligned by editor Sergio Jiménez. The film being shot both in 4:3 and on film also gives it a sense of the past whilst also retaining an organic sense of life through the flickering image. Recreations of Deckard’s various kills in Blade Runner appear as punctuation within these establishing shots, and his targets hold a thematic weight – the first kill is a builder high up on an empty construction site, representative of infrastructure and growth, and thereafter the killer takes down individuals who are emblematic of family, mass consumerism, and freedom of sexual expression.3

Just as the questioning of Deckard as Replicant in Blade Runner, de Sosa and co-writers Jorge Gil Munarriz and Chema García Ibarra allow the Deckard surrogate (played by the film’s sound designer, Manolo Marín) to have his own oblique sense of symbolism. Like one of his targets, he has a wife, yet unlike his targets he finds more in common with the nature of routine that the older people of the city follow. We only see these older couples in a montage sequence, awkwardly smiling at the camera, or in a dance class, where they are instructed via an unseen voice. Every one of the targets of the killer happen to be his age or younger, the (relative) youth the tool for snuffing out his own kind.

Whilst a lot of the abstraction of narrative works, there are some simple elements that distract and frustrate. The injection of what appear to be home movies mars a sense of tonal otherness, feeling like de Sosa has lazily re-purposed film scraps found on his desk as the false memories of the androids.4 Likewise, the limp dialogue citing a “space shuttle” and whether a character has slept with any humans also feel unneccessary in their efforts to represent elements of the source texts. Most of the imagery and pacing are able to conjure up a sense of Dick’s novel and Scott’s film without overreaching; the fact that so much of the film is silent is a testament to the power of the image in Sueñan los Androides. One of the more amusing active references to the novel is a scene in which the killer purchases a real and alive sheep for a very expensive price, its position in the structure of the film and the nature of the transaction far removed from Dick’s, yet here it captures beautifully his absurdly minimalist future, only to top it off with a car ride from the POV of the sheep, as the killer sings to it. As for Blade Runner, the most effective appropriation is a sense of tension. Early on we’re conditioned to expect a sudden gunshot taking out someone in frame, de Sosa plays off of that in the film’s middle, as a woman wiping down a shower door, the perfect opportunity to re-enact the death of Zhora through the glass, never faces the killer.

Sueñan los Androides is almost, at its heart, an act of misdirection. Whilst appearing to be a low-budget reincarnation of Blade Runner, it seems to actually use hyper-minimalist variations on genre tropes to make a statement about destructive forces in society and the rejection of the new. It’s an anti-future future, both visually and thematically.