In our column, Less Than (Five) Zero, we take a look at films that have received less than 50 logged watches on Letterboxd, aiming to discover hidden gems in independent and world cinema. In this instalment, Jeremy Elphick looks one of Christopher Doyle’s rare directorial outings.

Date Watched: 31th January, 2015

Letterboxd Views (at the time of viewing): 42

Christopher Doyle’s Away with Words (Dive Bar Blues) exists as one of his two forays into directing feature films; arguably, it is the sole work that shows the vast majority of the cinematographer’s talent applied to a significantly different role. The plot for the film isn’t groundbreaking, but that’s obviously not where its appeal lies. Kevin Sherlock plays the owner of the titular ‘dive bar’ and acts as the sheath to the protagonist, Asano. Asano posses a mnemonic memory, while Sherlock’s barely exists at all, torn apart by his constant alcohol-drenched endeavours. Night after night, Sherlock winds up in the police station due to his inability to even recall his own address – much to the stress of his colleagues and friends, most notably a woman played by Christa Hughes who becomes increasingly frustrated with Sherlock’s behaviour. In line with much of Doyle’s work, the film is whole-heartedly a letter to Hong Kong, however, unlike his more popular outings, Away with Words concerns itself primarily with the expatriate experience within the country.

Away with Words gives fans of Doyle’s work as a cinematographer an answer to the perpetual question of what exactly he brings to the consistently masterful films he works on vs. what is brought by the often established and loved filmmakers he works with. Throughout the flick, Doyle’s directing style draws a strong series of parallels with his approach to shooting – scenes, stories and dialogue are cut together in the fast-paced and professionally messy way in which Doyle puts together his shots. In terms of narrative, this can be difficult to follow at times, however Doyle’s appeal never sat in his mastery of storytelling through conventional methods. What Away with Words defines itself by is the constant contrast between low budget equipment and approaches with an incredibly high quality visual output; artistic, technical and tightly wrapping together the film in an aesthetic layer that defines it as a work highly worth watching. Doyle’s film offers another perspective – one markedly different than shown in his work with Kar-wai – into the city of Hong Kong so relentlessly romanticised in his ouvre.

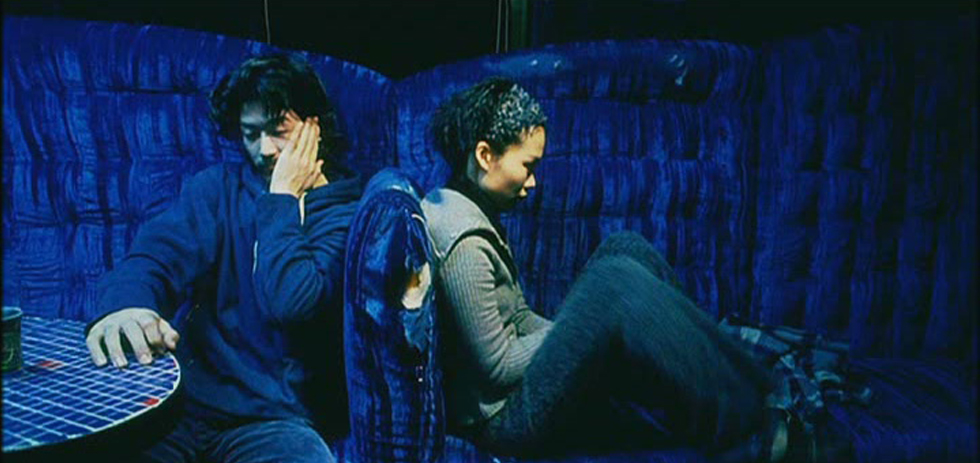

Doyle uses the same hypersaturation in his shots that defined his late 90s work in Happy Together and Chungking Express, although there are some clear distinctions between his solo work and his aforementioned collaborations with Kar-wai. This is most overt in Doyle’s use of colour. There’s a greater diversity in the saturation on screen and it makes a more colourful, comic and elated film. There is still darkness and a sombre sense of reflection, although Doyle tends towards a markedly more comedic, goofy and absurd filmmaking style. The result is particularly surreal in that throughout the film the audience is presented with the inimitably distinct style of Doyle’s cinematography that is ever-so-associated with Wong Kar-wai’s output, within the country where many of those movies take place. The difference is Doyle has inserted a handful of incredibly boisterous, both mysterious and confronting, energetic Australian actors into his ennui-laden, fast-paced vision of the Hong Kong cityscape.

Away With Words is an imprint in time that presents Christopher Doyle’s broad approach and vision of cinema in the late 90s. He’s a more jocular and satirical filmmaker than Kar-Wai and this comes across in his directing throughout the film. His film is never insincere, although the way in which it communicates sincerity is often part of a double-edged routine with sarcasm punctuating the other side. While Kar-Wai can take himself too seriously, at risk of being cliche – Doyle’s film heaves itself in the other direction. Doyle is an immensely talented filmmaker, arguably the most important and consistently in control cinematographer of his generation – his approach in the film is never forced, and this flow sits hand in hand with both his own sporadic and jumpy directing style as well as more technical efforts in his work with other directors.

The narrative that throws Asano through scenes of incredible contrasts doesn’t play the film’s strongest hand. It’s loosely inspired by Borges and his brand of jumpy, imaginative absurdism – and Doyle’s directing style (crouched alongside his cinematography) fall into place with the author’s thematic approach. Despite all of these narrative tendencies, Away with Words is an experimental film in all its other incarnations. Doyle’s camera work is as cutting and raw as ever, the plot is sliced up and thrown around in a manner that often makes it difficult to piece back together, and the characters drift in and out of Asano’s mnemonic realm of perception with the environments he pursues. That is to say, in essence, Away with Words feels and runs exactly how one would imagine a film directed, written and shot Christopher Doyle to. It’s beautiful, its cinematic style is poetic and it brushes back and forth over plot and narrative in a way that blurs them into the background with each stroke; to where they belong, the periphery.

The movie is an experience in subtlety and woefully underseen. It isn’t Doyle’s best work by any measure, however to watch it is to be given a rare insight into the directors approach to cinema (within the obvious budget and time constraints) in terms of writing, directing and cinematography in the late 90s and early 2000s. In his more recent work – especially his most recent directorial effort in the Hong Kong Trilogy (which we spoke to Doyle about) his style has evidently matured in some aspects. That said, there are some Doyle-marked aesthetic ideas in Away with Words that haven’t changed, and they’re all the better for it. Away with Words doesn’t match up against Doyle’s masterpieces, but it gives a more primordial presentation of the director / cinematographer / writer at his core. It’s fascinating to watch, it’s a slice of an incredible time period in Hong Kong cinema that no longer exists, and it’s a rare work from someone who has gone on to become one of cinema’s most lauded minds.