In our regular column, Less Than (Five) Zero, we take a look at films that have received less than 50 logged watches on Letterboxd, aiming to discover hidden gems in independent and world cinema. This week Conor Bateman looks at documentarian Jesse Moss’ debut feature, Con Man.

Date Watched: 12th February, 2015

Letterboxd Views (at the time of viewing): 4

Documentarian Jesse Moss has a knack for finding interesting and unusual subjects. He’s made films about demolition derby drivers (Speedo), a fake army invasion (Full Battle Rattle) and, just last year, achieved wide acclaim for his film The Overnighters, a cinéma vérité look at a blue-collar American community that supposedly defies all expectations (I haven’t had the chance to see it yet).1 In Con Man, though, his first feature documentary (albeit produced for HBO/Cinemax), Moss’ draw to the oft-chronicled ‘con man’ narrative is of a personal nature, in addition to being a compelling curio in its own right. As he narrates early on, con man James Arthur Hogue had once duped Moss and his high school classmates, posing as an orphan named Jay Huntsman, who grew up in a commune and was an athletics prodigy. It wasn’t until a local reporter, digging into the background of this superstar runner, discovered the death certificate for Jay Huntsman, a 2-day old baby who had passed away nearly two decades earlier, that Hogue’s identity theft was uncovered.

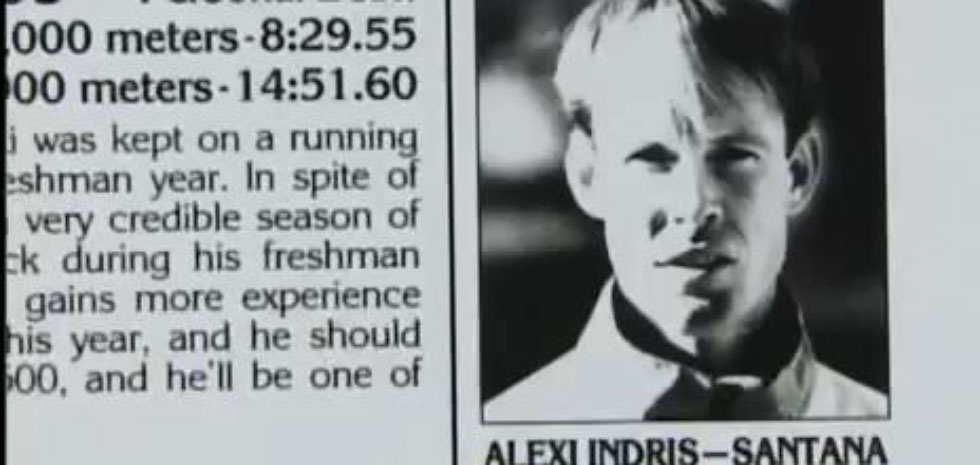

The personal connection makes Moss out to be something of a detective, he tells us the film took three years to make and was borne from his own obsession. He started filming after hearing the story of Hogue’s arrest at Princeton where he assumed the identity of the enigmatic (and fabricated) Alexi Santana. What would have just been a series of unusual newspaper stories from various states is stitched together by Moss as an hour-long feature, who pores over photos, articles and interviews reporters, classmates and detectives. In his director’s statement concerning the film, Moss said that “there was something romantic but also deeply disturbing about Hogue’s pathological desire to re-invent himself.”

Many of Moss’ interviews initially seem to be run of the mill made-for-TV talking heads, the on-the-nose surroundings (classmate in classroom etc), the slightly overdramatic piano music doing much to position it that way. As we circle back to them though, an intimate nature reveals itself. Every now and then the visage slips, whether by walking us through the house of a family of fencers, one of whom was Hogue’s cellmate following his Princeton arrest, or having a woman refusing to be on camera speak over footage of a view from her window. There’s a moment of beautiful chance in the fact that one of his interviewees, the reporter who wrote about and exposed Hogue when he attended Moss’ high school, thought during their interview that Moss himself was Hogue in disguise, getting revenge through impersonating a documentarian. When assured that Moss is not his man, the reporter utters a wonderful line that should be asked of any documentary – “why are you doing this?”

The thing that trips Hogue up in his deceptions, the one throughline, is running on the track team. Hogue’s defense attorney tells Moss that if you were trying to blend in at a university “the dumbest thing you could do is run track.” There’s a desire for attention or success, and when we delve into Hogue’s actual high school and college years, a complex starts to become clear. In college his position on the Wyoming running squad was overshadowed by Kenyan students eight years his senior (NCAA rules on athletes’ ages weren’t around then), so his looping of his own running career, an act of perpetual youth, is positioned as a response. There’s a poetry in Hogue’s passion for running too, his act of blending into a student body is also an act usually associated with escaping.

What is also interesting is that Moss doesn’t really lean too hard on a thesis for Hogue’s behavior. He presents us with snapshots of his early life and his friendships but leaves everything mostly open-ended, in particular the film’s end.

“Here in the midwest, you’re supposed to get the wool pulled over your eyes. But not Harvard, not Princeton, not the Ivy League”

Viewing Moss’ film now means it’s seen through the prism of Bart Layton’s superb The Imposter. The films differ wildly in aim and form, though. Layton’s is a hyperstylised half re-enactment of the con of impersonating a long-lost Texan boy. In Con Man, Moss focuses as much on Hogue as he does the idea of education and identity. Having conned his way into Princeton, partially as a result of athletics recruitment, Hogue excelled academically and athletically. An interesting argument arises about class division, pushed less by Moss than his interviewees, who note that Hogue himself, regardless of the name he had taken on, was the one getting superb marks at college and being the track star; having grown up in a very poor county in Kansas, Princeton truly a world away, his success is something of a marvel. The idea arises, then, that hard work shouldn’t be invalidated by someone’s past or background.

It’s easy to look back at Princeton and sneer, for having been duped by Hogue, but Moss doesn’t take that route, he’d been duped himself. The communications director of the college, though, is more than happy to make himself and his institution out as a punchline, when he looks into the camera and says “lying in part of your application to Princeton is not acceptable…ever” with a severity far and above any rational response. This university admissions focus also brings about the idea of Hogue’s actions being an almost victimless crime; the only real victim the pride and prestige of Princeton, resulting in a three-year prison sentence for Hogue.

Later in the film, Moss admits he’d reached something of a dead-end. He’d tracked Hogue’s life up until his prison sentence following Princeton, but beyond that he had no idea where Hogue was or how to find him, the only real next step for the film. This present-day narrative arc instantly becomes the most compelling element of the film, it feels less documentary than video-based investigative journalism.2 For a while we visit Colorado, tracking Hogue’s last known residence. Moss interviews Hogue’s old landlady, who fears reprisal, the first real indication of any malice on the part of Hogue. Adding to this shift is the camera work, Moss moves from the Digital Betacam footage of the interviews (hence the initial made-for-tv look), to Super-8 film, the flooding in of colour and instant evoking of a nostalgic impulse, likely for the viewer and Moss himself, makes this final section the most impressive on a filmic level, as well.

The real-time detective work continues until, out of the blue, Hogue gets in touch with Moss via a phone call. Suddenly the film cuts to their meeting, Hogue in the passenger seat of Moss’ car, who appears to be driving with one hand and filming Hogue with the other. The idea of interviewing a compulsive liar is an amusing one, and their conversations are far more compelling and spare than those shot earlier in the film with other interviewees. As Moss has written, “his responses to my questions were often evasive, and it quickly became apparent that Hogue had little interest in offering an emotionally introspective and narratively revealing account of his childhood, his deceptions, or his life after Princeton.” We hear Moss, slightly frustrated, asking questions from behind the camera whenever Hogue pauses mid-sentence.

The lack of verbal insight, though, then gives way to a projected emotional insight when Moss takes Hogue back to the Princeton campus, where he walks around for the first time since his arrest. The contrasting images of Hogue travelling down hallowed college corridors and those of him walking around his property in Utah, which is just a large block of land, is an interesting visual study in isolation. We find out that Hogue stayed a drifter of some kind, at the film’s end he is still going from city to city, making money by working in construction. He finds solace in this isolation and distance from his childhood surroundings, but one can’t help but wonder what would have come of him had no one seen him run track in a Princeton singlet, and found out that he wasn’t who he claimed to be; the tragedy of fear of embarrassment on the part of an institution outweighing the potential of the individual to transform, to learn, to evolve.