For a term so infamously overused, there is usually one missing ingredient in any definition of that nebulous label “Kafkaesque”. Used to describe anything from oppressive and incoherent bureaucracy or rather lazily, simply any surreal high-concept media, for me what defines Kafka is not just the bureaucracy or the absurdity, but how quickly the protagonist surrenders himself to them. Almost always tied to a protagonist, but told from the third person, the disconnect from our central character is essential to Kafka’s tales, and they become frustrating because the character comes to accept the new rules of the game on a pragmatic level the reader isn’t able to – of the many feelings his work provokes on an intellectual level, nothing erodes the desire to speak through the character’s voice, put your hands up and say “fuck this shit”. This passivity of Kafka’s protagonists, then, is one of the reasons why his work has endured. When read as political allegories, the opaque and oppressive political systems that govern our lives aren’t the problem his work apprehends, but our innate tendency to accept and adapt within these is what makes his work ultimately troubling. To achieve this dynamic at the expense of alienating the audience (or, to the direct ends of alienating the audience) is then to me what makes a successful adaptation of Kafka.

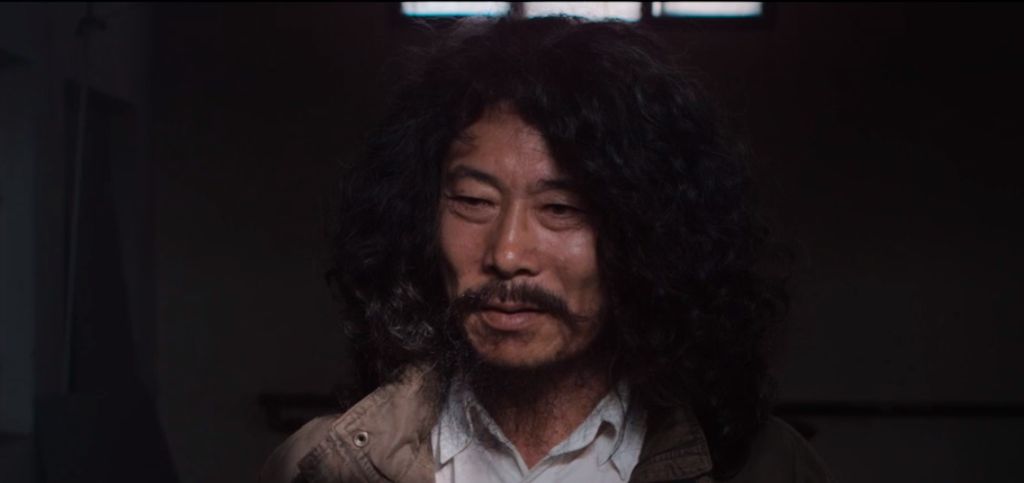

The second collaboration between Darhad Erdenibulag and Emyr ap Richard, K is an adaptation of Kafka’s unfinished novel The Castle (Der Schloss) transported to Inner Mongolia, and it’s an impressive film, understanding fundamentally how to adapt Kafka to a film script and perhaps most importantly, how to show it visually, even if the presumed political themes in this ethnocentric update remain elusive to those without a strong grounding in the sociopolitical currents of the region, which this reviewer certainly does not. The titular protagonist K (a committed, bushy-haired first-time actor Bayin) is summoned to a village as a land surveyor, under orders from the Castle, a bureaucratically sealed-off, seemingly omniscient form of governance that contacts K through a variety of often contradictory or otherwise senseless messages through the villagers. For the much of the film it remains a faithful adaptation (even retaining the Germanic character names such as Klamm and Frieda, for an extra disorientating effect), although like the novel, plot becomes inconsequential, as the book and now film’s strengths are largely derived from the tone and feel they create.

Visually, the film reinforces the uncertainty and frustration in the book, particularly in its evocation of the sense of spatial disorientation. The film avoids any establishing shots, and the action is constrained into claustrophobic rooms and corridors while giving us no temporal or geographical markers to make sense of the narrative or physical layout of the world of the film. There’s no shot of a castle, or even of the lack of a castle, reinforcing a visual style of a maze filled with natural lighting give the aesthetic an off-kilter naturalistic feel so that the audience never knows where any given part of the story fits into a grander narrative. It’s a slow, leisurely 85 minutes, where not every shot might be crucial to the economy of the film, but fits with the rest of the film and its tonally consistent, satisfying whole.

Most effective is the treatment of our nominal protagonist, in keeping with what I outlined above – in instances where the ambiguity of the novel can’t be adapted to the screen and the film needs to make choices one way or another, it errs on the side of making K even less identifiable. One particular choice best epitomises this approach – in the novel, K is provided with two assistants called Jeremiah and Arthur, who K cannot distinguish apart. We assume they do look identical, as K’s perspective is the only thing we trust in the mysterious universe of the book. However, in the film, there is no such ambiguity. The actors are clearly different people (accentuated by obvious physical details – one has a ponytail and the other doesn’t) so when K tells them they look identical it is less another mysterious element of the village, than an altogether more absurd realisation that our own perceptions directly contradict that of K’s. We can no longer ‘trust’ our only guide into the village, the person we arrived with. His actions become increasingly incomprehensible, less a visitor than one becoming slowly intertwined (literally) with the villagers. It’s an effective film, and as ambiguous and lost K seems to be in the final shot, it’s ultimately the spectator left out in the cold from the village’s inner mysteries, and that particular evocation of feel – the truly Kafkaesque – is where the film succeeds. With this in mind, the fact that the film keeps its own cards to its chest means it plays out with an intriguing metatextual resonance.