The Anthology Series is a new recurring roundtable column here at 4:3 where we look at the oft-overlooked genre of anthology films. Also known as portmanteaus, the anthology film is composed of a series of short films grouped together by theme or some awkward overarching premise. Some of the more popular portmanteaus in recent memory include Paris, je t’aime and horror anthology series V/H/S. There are also anthology films done by the same director, think Love Actually, Argentian Oscar-nominee Wild Tales and Robert Altman’s Short Cuts. For the purposes of this column, we will be focusing on anthology films with more than two directors.

In our first piece in this series, editors Conor Bateman and Jeremy Elphick look at the 2008 anthology film Tokyo!, with segments directed by Michel Gondry, Leos Carax and Bong Joon-ho.

The film has no home video release in Australia at present, so it can be viewed here on YouTube.

Conor Bateman: Tokyo! is a weird place to start for a series on anthology films, but that doesn’t mean it’s not an illuminating look into the mixed nature of the genre, or the way in which directors so firmly put their unique stamp on each short. What we’ve got here are three non-Japanese filmmakers — Michel Gondry, Leos Carax and Bong Joon-ho — ostensibly taking on the city of Tokyo, but it’s not even really that. Each of them touch on Tokyo-as-place, but the focus is always on character. The film was put together by producers who approached each filmmaker separately, commissioning them to make a short film about Tokyo, but it doesn’t seem like the idea of an anthology was at the forefront of any of their minds. Gondry has actually said of the whole Tokyo! project, “I’m not crazy about the project that the producers put together, the artificial excuse of “It’s a movie about this city,” but it was still a good opportunity that I took.”

Jeremy Elphick: I think it’s a good place to start. It’s not a pick that defines the anthology film by any measure. It’s not perfect, in some parts it’s remarkably average — but to me that’s what a lot of the best anthology films bring: an absolute gem among a selection of films that often accentuates the brilliance with their remarkable averageness. I think what makes Tokyo! a good starting point is how blunted these extremes are. None of the films are horrible, but none hold a candle to these directors’ magnum opuses.

Conor: Gondry’s short, Interior Design, is probably my favourite of the bunch. It’s playfully surreal (moreso as it goes on) but it’s primarily just so funny and romantic. It’s almost like a recent Swanberg film in the way in which dialogue so effectively endears us to these characters, only to create this quite beautifully constructed rift between them, the tipping point of which is this wonderful 3-min long take through the streets of Tokyo.1 The short is actually based off of a graphic (in form, not content) short story by Gabrielle Bell, called Cecil and Jordan in New York. Gondry’s shift from New York to Tokyo, though, isn’t that strange, as the narrative has this universal pull. That isn’t to say he doesn’t deal with the distinctive architecture of Tokyo, there’s a really playful sense of space, both within rooms and when walking through the streets, the wonder of the small spaces between buildings matched by an unknown apartment at the film’s end. It’s also great to see such strong performances in what is essentially a romantic comedy, Ryō Kase (who was in Funky Forest) and Ayako Fujitani (who would later co-write A Rose Reborn, a short film directed by Park Chan-wook) do some great work here.

Jeremy: I really like Gondry’s piece; it’s not my favourite of the three, but it’s not my least favourite either. I guess the most central thematic concern of the three pieces rests in the title, and Interior Design gives a potent take on a lot the more ennui-driven elements of Tokyo. It doesn’t romanticise it, and celebrates the mundanity and reality of things like trying to find a place to live and negotiating within the context of a relationship. Somehow, Gondry brings this together in a way that feels overwhelmingly pleasant. At the same time, this is probably what holds it back from being a super memorable short, but as its own piece, it’s definitely worth the time it takes to watch. On the other side of the coin there’s Merde, Carax’s short, and this is where things really took off for me, and I guess, really dropped off for a lot of viewers.

Merde is markedly experimental in nature and definitely the least palatable of the three sections, but at the same time, there’s something refreshingly abrasive about it all. Denis Lavant is cast as a sort of unspecified monster called Merde, a character he would also play in a segment of Carax’s Holy Motors. In this short, Merde dwells in the sewers of Tokyo and emerges to terrorise the locals in ways that often edge a lot closer to annoyance and harassment over anything truly terrifying. Lavant carries a lot of the short with his ability to convey such a genuinely palpable sense of malaise, the viewer can almost bring themselves to – not empathise with, but – sympathise with his absurdist and incessant state of being. Within the context of the film, Merde’s sense of loathing towards all things is both understandable and comic at times. I think one of my favourite parts of the section is in a scene in court where Merde is asked, “Why do you attack innocent people?”and he responds “I don’t like people.”

Carax was noted as wanted to paint Merde as not simply “a total monster” but also a foreign monster, unable to truly understand the city he finds himself in. Merde, for Carax is a “racist, fundamentalist Godzilla”. Most pertinently, Carax concluded in saying “Merde is a Mister Hyde cast into contemporary Tokyo. But then where is his double, his creator? Where is Doctor Jekyll hiding? In you, and in me.” I think a lot of the way the court scene operates doubles as a blueprint for approaching this film, and the way that Carax interacts with the audience. It leans a lot more towards the absurd and deconstructs a lot of expectations – he doesn’t explain his rage logically but chooses to reiterate the core of that same rage – that one would expect from a typical ‘monster movie’ and I think it’s a lot of fun in doing so. I know we’ll disagree, but this is definitely my favourite of the three.

Conor: I love how, as you mentioned, for a lot of people Carax’s short is often noted as the worst of the three, which seems hilarious to me, because whilst it’s not the strongest, it’s the only one with any real bite about it, actively tackling Japanese culture and the idea of modern terrorism and mass hysteria. It runs for too long, sure, but it’s intermittently glee-inducing, and I can see why it goes rambly and experimental, because it was Carax’s first piece of film in nearly a decade. Seen in that sense, that this and his later Holy Motors were an almost primal return to cinematic form, it explains why he seems to be throwing everything but the kitchen sink at it.

Jeremy: Yeah, I mean Lavant plays markedly different character/s in Holy Motors but Carax definitely has an eye for casting the actor as an exiled, dejected outsider. It’s a more primal and instinctual figure in Merde than the most defined and articulated character of Oscar in the director’s most recent film. That said, both occasions shows Carax completely in tune with an actor. Lavant and the director have a very special bond and artistic intimacy with one another that few of their contemporaries share. It’s what I feel gives Carax a bit of an unfair advantage in this anthology: he’s the only director working with his most long-term and effective collaborator. I think the results really seep through in a fantastic way with Merde.

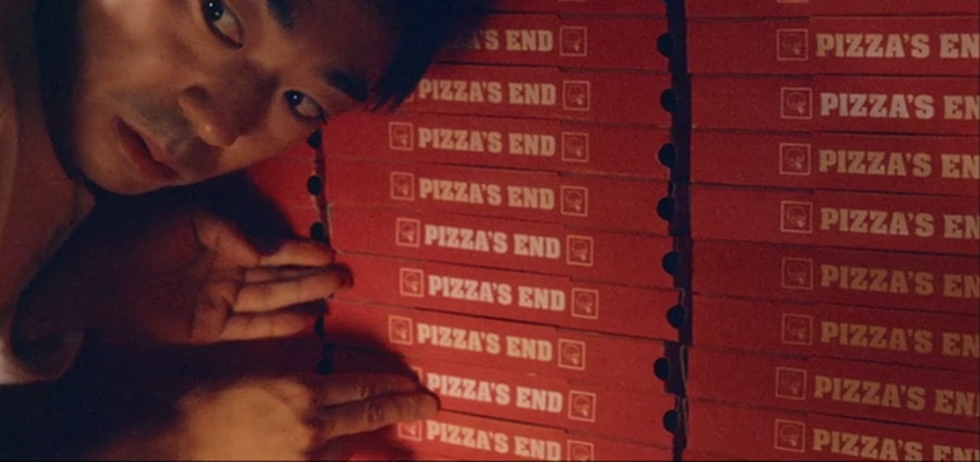

Conor: The final short in the film, Bong Joon-ho’s Shaking Tokyo, I’d often seen referred to as something transcendent, but it’s not quite at that level. It’s a love story as much about individual characters as it is fighting loneliness more broadly. Interestingly enough, it seems almost a precursor to a Korean feature that would be released a year later, Lee Hae-jun’s Castaway on the Moon, also featuring a shut-in. From a non-narrative perspective, though, there’s a lot to like here. The digitally stitched together “one-take” early on is as impressive as any in Birdman, and there is some really impressive cinematography throughout, regardless. I think I found it lacking in how it just fell on the saccharine at its end, whilst also perhaps trivialising the actual people who are hikikomori.

Jeremy: I feel this section does fall apart a bit. Sure, there are a few experimental takes from Bong Joon-ho when the hikikomori-esque lead emerges into the light and so forth, but it doesn’t really do much more but act as ornament to a largely imperfect piece of cinema. I feel the whole premise a bit flawed from the start as well and makes light of whatever caused the shut-in to be a shut-in for such a long period of time. It feels incomplete. Bong Joon-ho has an incredible ability to make both astounding films and absolutely middling ones. I guess this falls pretty firmly into that latter category.

Conor: It’s interesting looking at what each of these directors made after their Tokyo! segments, particularly relative to the quality of these shorts (at least in my eyes). Carax went on to make the internationally acclaimed oddity of Holy Motors, a film I admire but don’t love (a re-watch is definitely in store, considering how impressed I was with Mauvais Sang recently). Bong Joon-ho made (arguably) his masterpiece in Mother. Michel Gondry’s movements afterwards are strange and intriguing, including a Flight of the Conchords episode, a documentary about his aunt (called The Thorn in the Heart) and then followed that in 2011 with his worst feature film yet, The Green Hornet.

Jeremy: The end of the Golden Age of Gondry is an odd phenomenon, with The Green Hornet really being total trash. It’s nice to have this short film as a last requiem for the director in a way. I thought it was interesting how comfortable and enjoyable Gondry’s section was in Tokyo! without ever being too confronting. I thought it acted, in a way, as a really solid counterpoint to Carax’s more experimental approach to the thematic material but I thought it was far more interesting when placed side by side with Bong Joon-ho’s film. Both of them don’t tell particularly confronting stories, but Gondry’s is far more of a blueprint for how those more palatable shorts can fit into an anthology while Bong Joon-ho’s is more of an example of how it can go wrong in the most inoffensive way possible. This anthology could definitely be stronger from many different angles, but I genuinely feel like its worth a watch as a solid introduction to the expansive and weird world of portmanteaus.

Rankings

As part of this series, we ask all participants in the roundtables to rank the shorts within, not as a means of finding consensus but rather the opposite, an effort to show how varied segments within an anthology film can be, and the highly subjective nature in approaching them.

| Conor Bateman | Jeremy Elphick |

| 1. Interior Design, Michel Gondry 2. Merde, Leos Carax 3. Shaking Tokyo, Bong Joon-ho |

1. Merde, Leos Carax 2. Interior Design, Michel Gondry 3. Shaking Tokyo, Bong Joon-ho |