Editor’s Note (9th March 2016): This feature has been amended in light of Lilly Wachowski’s transition.

There’s an old binary that budding film-heads familiarise themselves with very quickly: ‘the artist’ and ‘the artless’. On the one hand, you have the daring director with an unimpeachable vision, and on the other a studio that bankrolls the film in exchange for its beating heart. This idea reps hardest when we first find an auteur to love, but it doesn’t account for people within the mainstream that might choose to blur that line, by playing to a wider audience and imparting their unique vision. Nobody pitches harder for that illusive goal than directors Lilly & Lana Wachowski.

If you follow this site’s recommendations, you would have caught their latest, Jupiter Ascending, before it is shoved off screens for more profitable fare. I have a less optimistic view than the one our own Conor Bateman expressed in his review – long rant writ short, both the central relationship and plot are too muted for my liking – but when he describes how its conceits feel sprung both from old-world storybooks and innovative action sequences, I have to nod in agreement. The pair’s seven films roam varying genres and moods, but this mix of awe and protest against the order of the universe is something that’s never gone away. Furthermore, as much as Conor diagnoses studio meddling in the end result,1 it feels like there’s a greater overlap between their goals and the old hands of mainstream film-making than on first appearances.

The Wachowskis take as tenets the same broad aspirations we would chide big-shot producers (e.g. Joel Silver, their collaborator on several releases) for employing, and then build the most mind-boggling conceits in its service. Things like fear, hope, purpose and love beg for derisive comments when talked about as nakedly as in their films, and they seem to anticipate and defy those responses, repeating those concerns again and again in the many climactic face-offs, pep talks and moments of out-loud introspection throughout their narratives. The belief that spurs them, as strongly as their protagonists are by their own sense of purpose, is that the same predictable nature of human choice is also what will set them free. The studio cannot trap these two because they are already trapped, wracked by fascination with the cosmic limits of human experience. Through story beats that are by turns euphoric and constricting, and throughout diverse planes of reality and human perception, the helix of fate and choice winds ever on.

It starts strong with Bound, their 1996 neo-noir romp and feature debut. I covered the film back in January for our You Have to See series, but I want to elaborate here on something I only teased out. Along with beginning their foraging from cinema’s past through the invocation of old-school thrillers, they use for the first time a technique that embodies their fascination with what humans make inevitable for themselves. The con of Bound hinges on knowing where the antagonist’s mind goes, so it is scoped out like the halls of a Vegas bank. We are treated not only to a scene where the two heroines lay their heist plan out for us, but one that weaves in jumps to the future where everything is pulled off without a hitch. This cross-cutting between two points on the same timeline is used to an opposite effect twelve years later in Speed Racer, when the titular hero comes undone at a major tourney while a malevolent race-rigger, squaring off with him in the days before, tells him exactly how. The world order that keeps the crook’s pockets lined, however, is what Speed will predict to then expose the fraud and put him in jail. The premise between the two is the same: whatever shell will be broken (LGBT oppression of the former, capitalist hoarding and de-individualisation of the latter, and the many other instances we will see elsewhere), the same predictability that keeps the world locked in a stupor is the thorn that the Wachowskis’ heroes will use to pierce through the veil.

In the years following Bound, the sisters left Hitchcock riffs aside in favour of more ambitious myth-making. Ever since Joseph Campbell excavated world myths in Hero With a Thousand Faces, the resulting Hero’s Journey model of narrative structure has been clung to by would-be screenwriters for better and worse. It’s all over The Matrix, and in revisiting it a decade-and-a-half after it crested the DVD wave, it would be easy to write it off as a film crafted solely for the benefit of the young boys for whom those Hollywood-friendly stories are often written. Keanu Reeves’ ascendance from office stooge to code-breaking ass whooper reads like an introvert’s wet dream, and the preponderance of black leather and Rage Against the Machine only highlights the masculine angst. Where it breaks away is a concurrent wryness and sincerity that gleams through even the cheesiest one-liners, thanks to a cast that does career-defining work across the board (particularly Hugo Weaving, Lawrence Fishburne and Gloria Foster). The joy is sustained when we watch Neo and friends jaunt across a green-tinged Sydney, finally giving a chunk of Australians the same tempo-spatial familiarity in a blockbuster that New York has enjoyed for decades. Such streaks of truth converge in the finale when Neo embraces his fateful near-immortality; a follow-through on the altering of reality hinted at by Bound, and a potent moment of epistemological triumph. Corky and Violet drove off into a sunset, while Neo flies rings around it, both having crossed the threshold of narrative and thematic satisfaction.

Audience satisfaction was much the same, though it took a couple of years to gather steam on the home entertainment market. Nothing speaks more to its seismic impact on modern pop culture than the cultural shorthands it spawned, good and bad. For every innocent description of a deviation from normal routine as “a glitch in the Matrix”, there’s a Men’s Rights Activist describing his hideous demonisation of women as the result of “taking the red pill”.2 By 2003, those plugged into this newly-minted brand name were ready to see just how much farther the rabbit-hole could go… and that brings us to the sequels.

The preferred behind-the scenes story is that the Wachowskis were keen to develop not the two follow-ups we received, The Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions, but a single one and a prequel that detailed the catastrophic war on the machines3. What stopped this, supposedly, was the studio brass balking at the idea of a Matrix film without the stars of the original; something too unprofitable to consider. Whatever the situation was, there were enough passionate fans of the Wachowskis’ for that art/money binary to rear its head again, and many still blame the latter for what we received. What’s true is that, while their shared plot is terribly stretched, there is a distinct feel across most of them that could have only come from their creators.

That’s especially true with Reloaded, which sums up its own agenda with one stark frame in a Machine World scene: solid streaks of red blood, crawling down a computer screen in parallel with the iconic green code crawl beneath. It takes the characters from being ordinary people trapped in a secret dystopia to superhuman Alices in a gonzo cybernetic Wonderland, talking shop with characters so eccentric that you wonder how they get away with being themselves. Figures like the Medusa-like Albinos, Persephone and the Merovingian are an unwieldy extension of the programs-as-people conceit from the first, and imbue a delightfully mythic feel that dives deeper into the franchise’s Campbellian origins4. This is carried on into fight sequences akin to Herculean trials, including the Smith clone fight, the Neo/Saraph duel and the second-half highway pursuit, all with incredible choreography by martial arts legend Yuen Woo-Ping. From the opening vision – yet again with invocations of fate! – through to the tete-a-tete between Neo and the Architect, the Matrix is transformed into a Tron-like playground of peril, and is a reinvigorated sight to behold. It’s also a bleak contrast to the newly-unveiled Zion, a mortal place where deaths from the first film matter and council war-planning stops for a sensual cave rave. In the battle for life against machines they created, and for purpose against a system designed to anticipate their every move, the cogs turn on what might be a powerful left turn for the series… until the cliffhanger ending comes along to leave threads hanging and a bad taste in the mouth.

Surely something this bursting with blood-red fury can find a decent resolution? With the ending arriving six months later, it wasn’t a long wait to be disappointed. Revolutions doesn’t end the series effectively, nor does it find a point of distinction worthy enough to be enjoyed like Reloaded. The gusto of its Biblical aspirations is commendable – how many movies list a character as “Deus Ex Machina”? – but it falls fatally short of alleviating the dourness and boredom filling the two-plus hours that come before5. Early scenes of Neo being stuck in a mid-world train station is just wheel-spinning, and the Zion stand-off is especially tiresome, thinning out its action beats in a way not surpassed in a blockbuster until Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit films. It only picks up steam with the superheroic final clash between Neo and Smith, not just for its anime-like bombast but for the brief hints of encapsulating the Wachowskis’ fate-versus-agency fascination. In the midst of sleek pans and slow-mo shots scored hyperbolically by Don Davis, we see fleeting symbols of spiritual sacrifice and selflessness, and glimpses of the duo’s unfettered thoughts on what it takes to shape an ideologically stubborn world. There’s a promise of satisfaction within the lust for scope, but given how the wider story runs aground, it’s something we’d have to wait longer to see.

After that steady letdown, the siblings made their first retreat from the directors’ chair into producing, giving their AD James McTeigue one hell of an opportunity by adapting Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta, which has much the same energising effect as The Matrix with its symbols of modern protest and activism. They’re also listed on the re-writing credits for The Invasion, the last of several Body-Snatchers remakes, which may not have done well but seems to indicate a lingering trust in them by the studio that financed The Matrix to begin with. I suspect it’s what got their foot in the door for the insanity that came next.

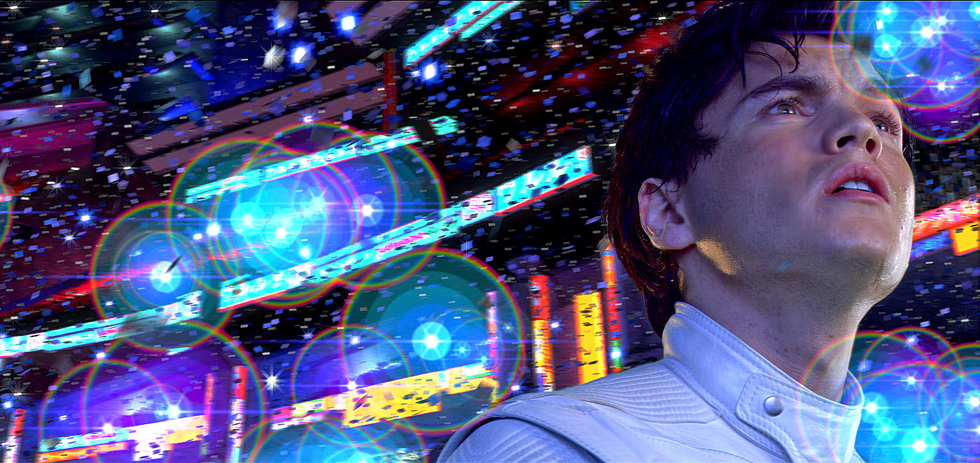

I always adore when studio logos are tweaked in a film, because for that moment, I feel I’m in for something special. That’s present in the acid-green coating of the Matrixes, but I’ve yet to see any film deliver better on that feeling than Speed Racer. It sends the logos of its benefactors through a lurid kaleidoscope, and then does the same for Saturday-morning aesthetic wholesomeness in a film that deserves its cult following and then some. An adaptation of an existing property was already a novel way for the Wachowskis to follow their biggest achievement, but a 1960s anime better known for its mangled American dub than the strength of its story is bizarre source material indeed, and there is none of that weirdness spared. The good-and-evil face-off found here is between the Racer family, headed by the most headstrong young buck imaginable (Emile Hirsch), and the corporate octopus of the Royalton company, whose namesake is played with glorious venom by secret Vendetta MVP Roger Allam. As far as battles for the future go, nothing could be more pure in function and intent than a big race; something with the simplest of stakes and the most identifiable of skills. Throw in racers and machines with Mario Kart-like variation and you have on-screen face-offs that take the highway chase of Reloaded into a lurid new form of cinematic action. The off-track action, spent mostly with Hirsch and his family (Christina Ricci, John Goodman, Susan Sarandon and others) takes detours into warmly familiar territory for the directing couple: fist-slinging fights, stony-faced exchanges (best made by Matthew Fox, who is in the role of his career here) and odd moments of kiddy glee involving a certain boy and his monkey. Still, it’s the races that fuel the thing, and distil their showdowns between man and system in a way that feels broad yet deeply renewing after Revolutions. Flop or not, they were back on form.

This particular film is why I was never taken with Jupiter‘s world-building touches, which might have given me the self-contained experience that Conor describes it to be. The details here are nuts, but being cartoon characters, their immediate visual signifiers are enough, and don’t need the careful delineation in the manner of something gunning for franchise status. Bubble-foam crash shields? Got it. Vikings? Makes sense. Beehive catapult? OK, sure. The thing is the thing. And it’s not just the details, but the whole aesthetic of the film – blue-screen environs done gaudy on purpose, depths of field squashed together like cartoon frames, screenwipes hardly seen before or since and Michael Giacchino absolutely killing it on a rollicking, surf rock-inflected score. This is a world where the podium winners drink milk, and that determined innocence brings a light touch to the pair’s capitalist-monopoly musings.

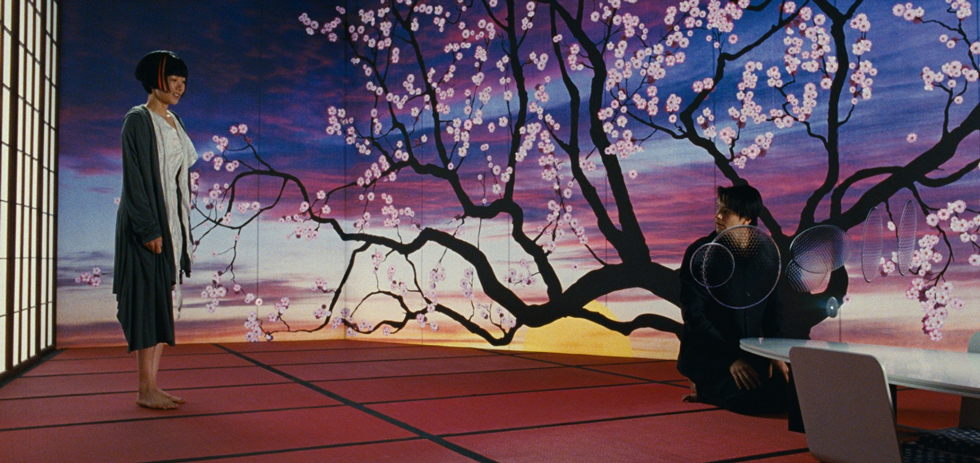

So of course it failed, critically and commercially, and once again the Wachowskis slunk away from the limelight to give McTeigue a leg-up, producing the slight but goofy Ninja Assassin as a vehicle for Korean pop star Rain. But someone explain what possessed them to take their next step: collaborating with Run Lola Run director Tom Tykwer to adapt head-spinning novel by modern literary maestro David Mitchell in one of the largest independent productions in cinema history? Their German investors have der mut the likes of which I live to gain, not just because of the price tag but because Cloud Atlas is surely the Wachowskis’ magnum opus. Mitchell’s novel uses recurrence across six stories of different times and genres to create a secular kind of nirvana, and rather than recreate the readers’ journey of discovery through the layered text, the Wachowskis and Tykwer rebuild those layers as a way of aligning us with their own. Scenes and scenarios are slided across the timeline to augment one another in free-form ways, like the precognitive moments of Bound and Speed Racer blown out to feature length.

Out of those, the ones that the siblings direct (with Tykwer taking the remainder) continue to mix the old and new in novel ways: a breath-taking people’s revolution in the future metropolis of Neo-Seoul (with a simple but sweet romance that beats the pants off Jupiter‘s). The second is essentially a fantasy quest, taking place across a far-future Hawaii and starring a hero (Tom Hanks) beset by his own barbaric impulses at every turn, in the form of a slimy devil played by Weaving. Chronologically preceding these is a radiant high-seas adventure that brings the film’s meta-story of actor re-casting into sharpest relief, since Jim Sturgess’ Adam Ewing finds his loved one (Boona Dae) again in Neo-Seoul and Hanks’ malevolent quack finds redemption as a warrior of the post-apocalypse. In the fracturing of plotlines, the delineations of genres, character types and expectations thereof blur into their grandest symphony. Nowhere else are the accusations of preschool bluntness more frequent, nor are they more defiantly sentimental, and for the weight of the systems being torn down by the main characters’ iconoclasm, nowhere is it more justified.

The recurrence conceit is such a cap to their ongoing trends that it’s little wonder critics like Matt Zoller Seitz see Jupiter Ascending, a hardline attempt at Flash Gordon space fairy-tale, as such a regression. Conor might have denounced its capacity for a cult following, but recent reports indicate that its stranger elements are finding a home with different kinds of audiences than the norm. I’m keen to revisit the movie someday and see if its myriad of visual ideas carries across any better, along with the passion present in all of their past movies. In the meantime, their next project is Sens8, a Netflix series that follows eight mentally-linked individuals around the globe, which sounds like a longform treatment of their usual themes and something I’m stunned hasn’t come to fruition before. Wherever they go next, they’ve already notched up amazing work with a life that will, as Cloud Atlas‘ Frobisher (Ben Whishaw) intones, extend far beyond the limitations of them. Their hybrids of cinematic forms, familiar and foreign, commercial and creative, are deeply sincere and awesome gestures for which immortality seems like the only fitting reward.