You Have to See… is a weekly feature here at 4:3, where one staff writer picks a film they love and makes a group of other writers watch it for the first time. Once this group has seen the film, the suggestor writes a piece advocating the film and the others respond below. Whilst not explicitly spoiling the film, the article is detailed. We would recommend seeking out and watching the film each week, then joining in the debate in the comments section.

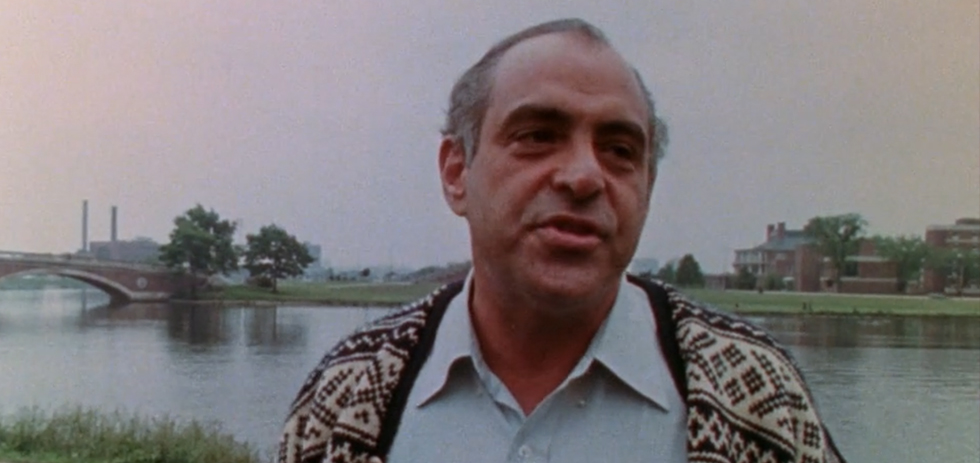

This week Jeremy Elphick looks at Dušan Makavejev’s W.R. Mysteries of the Organism, the director’s most well-known piece and one of the defining films of the Yugoslav Black Wave.

In one of the more famous entries in Dušan Makavejev’s filmography, there is a line that Roger Ebert asserted could have been uttered by the director himself: “Gentlemen, I assure you the entire Yugoslavian cinema came out of my navel. In fact, I have made certain inquiries, and I am in a position to state positively that the entire Bulgarian cinema came out of my navel as well.”

Though within the film the line is simply another acerbic piece of Makavejev’s absurdist wit, it is a wit that mapped out the foundations of Black Wave, a movement in 1960s and 1970s Yugoslav film that was cinematically niche but creatively expansive. For Ebert, the line, which is from Innocence Unprotected, is indicative of something more specific: Makavejev’s place within Eastern European cinema. And while Innocence Unprotected is one of his more well-known pieces, it is W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism that is widely considered to be Dušan Makavejev’s masterpiece.

There’s already a substantial amount written and said about Makavejev as a filmmaker and most of it centres on W.R. So why add to an already dense discourse? Non-Western European cinema from the 60s and 70s is often categorised as a genre with particular exclusivity, cast as somewhat impenetrable. Makavejev as a director – and W.R., specifically, as a film – has occupied this closed-off area of cinema that is foreign political art house. Against this, I’m going to argue throughout this essay that Makavejev’s film is far from inaccessible and, instead, is something that should be widely seen. It’s weird, yes, and it can be unashamedly political and intellectual – but that doesn’t mean you have to agree with everything it expounds upon or drives its critiques into.

Eastern European cinema in the 1960s and 1970s tends to be sidelined as an imaginative, ‘crazy’, and aesthetically wild movement that offers some solid works but that shouldn’t really be held up against the magnum opuses of Western Europe. Certainly, Eastern European cinema has a confronting strangeness that unsettles the familiar – and this is particularly true of Makavejev’s Black Wave. However, the inversion of this is that what Makavejev presents in W.R, is refreshingly unique, even 40 years on. It is a wildly ambitious film. The satirical elements of his comedy remain markedly on point and the experimental approach to form creates a destabilisation that is characteristic to the experience of Makavejev’s cinema.

W.R. opens with its guiding dictum:

“This film is, in part, a personal response to the life and teaching of Dr. Wilhelm Reich. Studying orgasmic reflex, as Sigmund Freud’s first assistant, Reich discovered life energy, revealing the deep roots of fear of freedom, fear of truth, and fear of love in contemporary humans. All his life Reich fought against pornography in sex and politics. He believed in work-democracy, in an organic society based on liberated work and love. Dr. Wilhem Reich. Joy of life. Enjoy. Feel. Laugh.”

This intersection between communism and sexuality and the desire for a theorised liberation that sits at such a point, is the theme around which the film coheres. Within this, however, there are three main lines for discussion: its narrative; documentary excerpts; the re-stagings of communist tales and voiceovers that punctuates these scenes within the film. W.R. doesn’t aim for linearity or narrative coherence. The film is, instead, insistently thematic: it is concerned with sexuality, it is concerned with politics, it is concerned with their intersection as a potential state of revolution, or imprisonment. Though rife with on-screen nudity and un-simulated sex, it’s not a pornographic film. W.R. is a film about sex, but only insofar as the politics of sexuality are matters of sex.

The context that W.R. emerges articulates the key reason for its initial pariah status. Jonathan Rosenbaum suggested that Black Wave cinema marked itself as outsider movement simply in origin: the genre emerged from Communist countries, creating cinema that was “much harder for Westerners to place, process, and understand; in most cases, an adequate sense of context was lacking.” Makavejev’s film engages heavily with Communist aesthetics and presents itself as a byproduct of the countries and political contexts that informed it. However, Makavejev never toes a political line with any straight resemblance to Soviet Marxism. W.R. posits a dual sense of agitation to two different systems: the specific strand of Marxism dominant in Russia at the time and the increasingly influential psychiatry in the USA. Through this duality, Makavejev positions psychoanalysis, and its medicalised counterpart of psychiatry, as an ideology as much as a discipline.

While Rosenbaum argues Westerners approaching W.R. lack a certain context for analysis, I would suggest that this was intentional on the part of Makavejev. It feels almost as if the director was able to provide more routes of accessibility but chose to remove them in order to create something remarkably nuanced and multi-faceted in its criticisms and ideas.

The film is not a naïve attempt to romanticise a distant or mysterious discipline. Psychiatry, in fact, was Makavejev’s field of study before moving into film. There is a degree of fascination that permeates his work but also a strong curiosity that is as critical of psychiatry as it is reverent. Makavejev’s portrayal of Communism mirrors his portrayal of psychoanalysis, teetering between fleeting acquiescence and aloof appraisal. He uses footage excerpts from completely sincere documentaries that idolise Stalin and record Reich’s particular strand of psychoanalysis, and pieces that establish the mutual distance in Russian and American perceptions of the other.

The fiction and narrative elements of the film, in contrast, are almost wholly comic or simply absurd. In an interview Makavejev makes a fairly revealing comment on this duality in his film: “Maybe it is like a mirror. People hold it up to themselves and see reflected only what they are most offended by.” In Russia, and some of Eastern Europe, his work was banned for being seen to mock or delegitimise Soviet Communism. In America, the presentation of sex in the film and what was seen as the trivialisation of Reich’s ideas was taken as pornographic. In this alone, a viewer today approaches the film with this as an established historical context: that somehow, W.R. brought two otherwise diametrically opposed positions into an odd unity through a shared and equal outrage. Though in theory wholly hostile and divergent ideologies, W.R managed to demonstrate a point of manifest pragmatic similarities that neither would likely admit.

Though Reich’s writings examined the relationship between sexuality and politics, he placed more emphasis on sexuality, and Makavejev brings these ideas to his film in a nuanced, critical, demonstrative and complex process by placing them in a variety of situations. Throughout, Reich’s fear of Soviet Communism as a totalitarian and authoritarian world is implicit in the markedly separate idea of the intersection between sexuality and politics. On the other hand, Reich’s fear of Soviet Communism is, at times, mocked by Makavejev, who sees in American psychiatry the same ideas of mass control and restriction appearing in a different context. One scene focuses on hundreds of people lying on their backs, being stood on, groaning in what appears to be a sexual form of therapy. The way Makavejev positions it within the body of the film places it alongside the same sense of fascism Reich aims to critique. In the American scenes, the idea of the family is laughed at as two cross dressers eat ice-cream on the street and discuss their relationship. They discuss a street performer, Tuli, as “all american”, as a sort of ideal state, while “Teach Your Children” – the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young ballad of fidelity – plays in the background, articulating a scene of hypocrisy, fragility and establishing another parallel with.

Milena and Jagoda, two Yugoslavian women, are protagonists of the fictional side of the film. Their tale is absurd, political and arguably the most entertaining part of W.R. Together, the two women present an idealised portrait of sexual and political liberation, while neither is able to present the whole on their own. Milena is the intellectual, wanting to merge sexual liberation with the idealised Communism. That said, she spends the film proselytising about this intersection, discussing free love with those in her apartment complex and giving inspiring speeches but never engaging in the state she articulates so fondly. Jagoda inverts this. She is concerned with a very physical sexual freedom – sensual in both senses of the word. Shots of her having intercourse cut alongside those of Milena giving the aforementioned speeches and when Milena announces “between socialism and physical love there can be no conflict”, the constant jumping between her announcement and Jagoda’s physical love seems to be an implicit iteration by Makavejev that such a conflict remains.

Milena and Jagoda’s Belgrade residence is littered with subtle comedic parallels between the East and the USA, with every jab at Soviet Communism met with another at the state of psychiatry in America. For instance, rather than having a portrait of Lenin or Stalin on their wall, Milena and Jagoda have paintings of Freud and Reich, with a less-than-subtle implication from Makavejev on the idolisation of figures to a certain extent where the idol overtakes the substance. This takes form particularly in the introduction of Illych. Vladmir Illych, sharing his name with the man who became known as Lenin is referred to in W.R. as “the people’s artist” and quickly viewed as an ideal “erotic” figure by Milena. “He’s a champion and a communist” she says at one stage: but like every idealisation presented throughout the film, this too is shattered.

The film is nuanced in its portrayal of the politics of sexuality and vice versa. Rosenbaum articulates that the position of elements of communism as absurd is equally prevalent in the presentation of Reich’s views on sexuality: “Makavejev perceives sex as an unleashing of potentially dangerous energies that threaten not only puritanical and authoritarian systems but also, in some limit cases, sanity”. In the scenes where adherents to Reich’s form of psychiatry are at their most desperate, their most faithful and their most nonsensical it should also be noted that they aren’t dissimilar from those on the other side of the spectrum, where sexuality has received far less of a focus than the political sphere. As W.R. progresses and its limits and ideas become more drawn out and clear to the viewer it becomes far more obvious what sort of a film Makavejev is trying to make. Throughout its duration, the criticisms of Communism and their parallels in the detractions towards Reich are not meant to represent any stringent political views on the part of the filmmaker. Towards the end, it’s clear that these are interchangeable case studies in proving a larger point for Makavejev. Sex is at the centre of the film, and the two societies within are used simply as the most opposing possible examples to present a critical cinematic presentation of the way in which these oppositions emerge and grow; how at their extremes and ends there is such a mutual sense of conflict and expedience on both sides where neither is more legitimate than the other. They are both absurd imitations of the other as a result of the intricate, careful and heavily cinematic presentation of their most extreme elements throughout Makavejev’s film. In itself, W.R. is a piece that shows the capabilities that film possesses, both as its own example and as a catalogue of those that it positions within itself.

In 1971, Ebert summarised W.R. as putting forth an argument that “if we were not so rigid” and could release our sexual human energy, we would “achieve greater sexual satisfaction and cure the ailments of Soviet Marxism and solve the problems of American Puritanism,” before continuing that, “if the Russians cannot smile about politics, we Americans are positively long-faced about sex.” Years later, in 2007, Ebert wistfully reflected on W.R. as a lost form of political provocation, lamenting that “movies like this are impossible now.”

I think on one level he’s correct and on another he’s falling a bit short: Joshua Oppenheimer, who was mentored by Makavejev, has clearly seen his own style largely influenced by the director. He discussed the final scene of W.R. in which Illych sings “self‑pityingly” after he has decapitated Milena: “The injury is somehow no longer at all about him as a character feeling self‑pity. It’s about the history of fascism—the tragedy of the inevitable corruption of our efforts to mastermind utopian societies in the twentieth century—and the enormous, unthinkable violence that results from that.” Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing re-contextualising a lot of the ideas expressed by Makavejev in W.R. It organises a vast amount of its key ideas around a more particular case study, while Makavejev articulates them in their essence. With Oppenheimer’s success and clear reverence of his mentors politics and such, alongside the late Ebert’s love of Makavejev’s cinema, perhaps it is time to reconsider the place of W.R. in the archive of film: as a film more deserving than simply being viewed as one of the most intriguing “weird” films out of Eastern Europe in the 70s – as something you have to see.

Responses

Ivan Čerečina: Rewatching this, I was struck by how sui generis the composition of Makavejev’s film is, and how difficult it is to define where exactly it sits in cinema history. Jeremy briefly alluded to the co-existence of documentary and fiction in his write up, but it’s worth pointing out the sheer range and diversity of elements that make up the film: there’s archival footage of official ceremonies featuring both Stalin and Mao, excerpts from Soviet propaganda films, footage shot by Makavejev’s crew in Reich’s last home in Maine, short comedic sketches on the streets of Manhattan featuring counterculture hero Tuli Kupferberg,1 confronting footage of now-archaic treatment practices of mental traumas, and a fictional narrative set in the former Yugoslavia.

What makes this one of Makavejev’s more interesting works is the way he weaves these disparate elements together, allowing each segment to exist separately rather than forcing them into a unified whole. For example, he doesn’t introduce the protagonists of the film until about half an hour in, preferring instead to begin the film with a patient portrait of Wilhelm Reich’s final hometown of Rangeley, Maine. Though not entirely disconnected from the ideas floated in this opening half hour, the introduction of the protagonists is marked by their (theatrical and farcical) reflections on personal politics in Yugoslavia. As such, gleaning a singular political thesis from the film is difficult, but perhaps that’s not Makavejev’s aim here. As Jeremy pointed out, it is equally critical of repressive U.S. small town politics as it is of the Soviet Union’s own oppressive imperialist model of Communism behind the Iron Curtain. With regards to the latter, probably the most revealing passage of dialogue in the film occurs between the two Yugoslav women – Milena and Jagoda – and Vladimir Ilyich, a Soviet ice-skater and self-proclaimed People’s Artist.2 Asked about the state of personal happiness in the Soviet Union, Vladimir Ilyich – who strictly toes the party line with all of his rhetoric – replies proudly that they have abolished the difference between personal happiness and the “happiness of the People”, that there is no longer any distinction between the two. The women counter, saying that in Yugoslavia there is also no distinction between personal happiness and that of the People: neither of them have been achieved. Here, the delicate situation of Yugoslavia as a socialist nation that had formally split from its alignment with the Soviet Union two decades prior is brought into relief. Between the marxist orthodoxy of the Soviet-aligned Eastern Bloc and the liberalist economic model of the NATO countries, the country was attempting to forge its own path; it must be said that Makavejev is unclear as to what this path ought to look like, other than maintaining that personal freedom must not be compromised.

But this ideological ambiguity is precisely what makes W.R. so unique as a piece of political filmmaking from this period. Contrary to so many of the other engaged, militant works of filmmaking in the late 60s and 70s – in both the East and West of Europe – Makavejev’s film is political without being didactic. In this sense, it’s an interesting document of the ideological debates coming out of Yugoslavia in the period, a country experimenting with a “third way” between the ironclad ideologies of the East and West.

Andrej Trbojevic: Psychoanalysis, as we know from its many influential acolytes in surrealist painting (Dali, Breton), modernist literature (Woolf, Roth), and cinema (every Hitchcock film ever etc.), made an indelible impact on art history. In a sense it could be seen as having liberated the chaotic, fructifying unconscious energies that lay dormant, repressed, beneath the millennia in which art desperately attempted to relegate itself to a merely mimetic task, to naturalism. It is more than historical coincidence that Picasso, so important for the experimentation with abstraction, made his well-known statement “I have never seen a natural work of art” after the advent of psychoanalysis and his own stint with surrealism. Makavejev’s Mysteries of the Organism may safely be placed in a genealogy with this attitude, for it is most definitely not a “natural” work of art, a “natural” work of cinema, nor does it aspire to be. Yet it is also not its politically complicit binary – an “unnatural” work of art, unless of course you facilitated Wilhelm Reich’s incarceration or were a Yugoslav censor in some previous life, in which case this film is entirely for you, and above all, your lifetime of having ignored your conscience.

As such, and given Makavejev’s flirtation with the psychiatric vocation as Jeremy mentioned, a couple of maxims in psychoanalysis go a long way to explaining the significance of this film, at least conceptually. One of the guiding principles of psychoanalysis’ understanding of the human subject, in particular the manner in which it is constructed, shaped or “subjectivated” by the social and ideological milieu the subject finds themselves in, is that every society (in particular those that aimed at the teleological resolution of all of life’s contradictions) prohibits the expression of some truth, leaves something unsaid and unsayable. WR may be seen as the attempt to say as much of these “transgressive” truths as possible, for somewhere in the deeply human, interstitial space of the consumer/hedonic treadmill of the West, and the grotesquery of the Party’s inexorable march to a society literally inspired by the Kafkaesque, is a hard, ejaculating cock and lubricated vulva, totems of the irrepressible, inexhaustible urge to live, to an inner, refulgent dynamism that reminds us, as Milena does in her hilarious, sincere and blustering speeches to her fellow apartment-complex denizens, that there are no limits to love, and to freedom. The other assertion made by psychoanalysis, in particular the more anthropological bent of Lacan, is that life is a fiction, ensconced in its more or less arbitrary symbolic universe, and conversely that there is more truth in fiction. Compare Channel 9 ‘ANZAC Day’ coverage to Remarque’s All Quiet…

The function of Makavejev’s absurdity, which in its defiance of conventional narrative cohesion and the documentary/drama chasm exemplifies a real joie de vivre, love of creativity and passion for the human condition, disarms and trivialises the true absurdity of the ideological and geopolitical camps that to this day point their nuclear warheads at one another. And how camp they are. When juxtaposed to the true signifier of liberty in the film: a gelatinous mould of an erection freed from its plaster prison, the fanatical ovations directed by Stalin in the East and tales of hicks pointing their rifles at WR’s home in the deep South are shown for what they truly are: perversions, and moreover, bedfellows in their puritanical attempt to hold back the limitless agitated for by the human spirit. As Jeremy stated eloquently, in its unashamed embrace of the absurd it deconstructed the ostensibly hostile and opposed regimes perfectly by eliciting, in a painful irony, the exact same condemnatory and overbearing responses. You can’t ask anything more from a work of art.

Yet I would just like to add that there is a bizarre poignancy to the film that stays with you long after the viewing. With the absence of any real beginning, middle and end, with the lack of any real resolution to the character’s plights and conflicts who more or less appear and disappear willy-nilly, it somehow frees and absolves us of our mad attempts to find temporal anchorage and subjective sense and coherence in this, and when faced with the wry smile of a photograph of Reich, implores us to suspend our disbelieving selves, for what is an ideal future compared to a touch? The answer: a talking, severed head on a disinfected hospital gurney.

W.R. Mysteries of the Organism is available on DVD from the Criterion Collection.