In our regular column, Less Than (Five) Zero, we take a look at films that have received less than 50 logged watches on Letterboxd, aiming to discover hidden gems in independent and world cinema. This week Jake Moody looks at film that falls outside of the Letterboxd database, Frederick Wiseman’s Essene.

Date Watched: 27 May, 2015

Letterboxd Views (at the time of viewing): 28

The long and storied career of Frederick Wiseman is interesting not just because of the determined, penetrative nature of the films it has produced, but also because of a thematic consistency rare in a modern documentarian. When his National Gallery and At Berkeley screened at last year’s SFF, for example, they epitomised his body of work – compounded it – rather than necessarily complicating it. For a filmmaker as consistent as Wiseman, then, we have to adjust our focus. Like John Ford, the real rewards lie in dissecting the minute and telling variations between the tone and construction of his works. His single-minded cinéma vérité studies of American institutions are challenging, usually in their exposure of the frustrated and dispossessed at the mercy of these bodies, but also in their starkness. Films like Titicut Follies, a controversial 1968 fly-on-the-wall study of a sanitarium, and the later Hospital, High School, Welfare et al. are pointed in their detachment, sparse and bare of camera flourishes or metaphorical editing work. It may be meaningful, then, that those of Wiseman’s films don’t qualify for this column, too widely seen (if still woefully under-appreciated) and too much a part of the American outsider non-narrative canon. What Essene, a 1972 study of a modern-day Benedictine monastery in Michigan, represents is a foray into some sense of stylisation, or deviation from Wiseman’s typical dogged naturalism. Moving from the everyday chaos of medical or educational establishments to a more spiritual realm necessitates a different approach, and Wiseman’s subtlety, humanity, and wit work to create one of the most powerful of his films.

Essene1 begins with a striking scene typical of Wiseman, ‘in medias res’, with a set of functionaries who work in and around its central institution embroiled in a meeting. Their discussion, like most which take place in esoteric situations like workplaces and community groups, is dry on the face of it – the men take turns to raise points about the best way to ensure they work well together observing the kind of formal etiquette familiar to boardrooms and conferences, never speaking over one another, measuring their words. There is a jarring setting though: the various men involved are clad in dark robes, wear heavy crosses, and discuss not their relationship with balance books, patients, or clients, but God. This opening sequence introduces the main juxtaposition which runs through Essene, of modernity set against the obviously arcane traditions of monastic life. It’s easy to see how this would fascinate any documentarian worth their salt – for starters, the monks occupy an American space rather than continuing any ancient European tradition, rendering their more overt Seventies traits unwittingly comical.

While we might associate this kind of ascetic commitment to faith with elderly men living hermit-like, outside of time, the monks of Essene are unavoidably modern. One difficult brother, Wilfred, seems more like a character from the Maysles’ Salesman than a celibate Catholic acolyte; pressed by Wiseman on why he finds it so hard to gel with others, he becomes increasingly irate as he describes the ways that other people try to befriend him. Those who address him by his first name, acquaintances who attempt to make idle conversation, the fly buzzing around the room – all are in for equal contempt, with Wilfred’s mundane earthly grumbling completely at odds with his dark habit and supposed spiritual commitment. The other brothers are similarly anachronistic, chatting amongst one another of their visits to Manhattan and their old friends from college while pledging their servitude to God. One of the monks, a young Japanese-American man whose long hair and wistfulness would make conventional wisdom probably place him at Woodstock, makes a thoughtful contribution to the discussion, and ends with a presumably personal prayer for those affected by the ongoing fallout from the Hiroshima bombing. Departing from the purposefully everyday to instead explore a fundamentally fringe organisation necessitates that Wiseman’s unobtrusive style be compromised – he cannot use his camera as a pure ‘window’ when the institution his film explores is not a representative document of time and place, but instead a strange hybrid of a place, at once therapy, refuge, opportunity, and prison for its brothers.

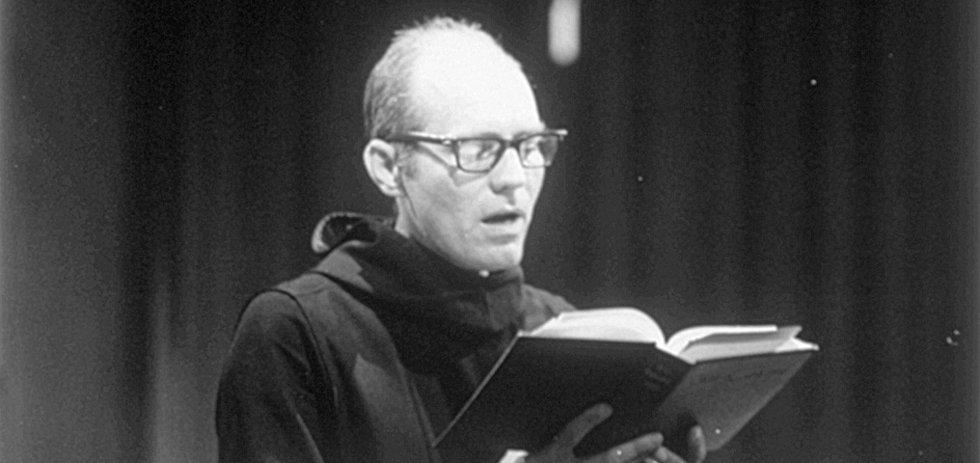

Recognising Essene as an anomalous work within his oeuvre appears to have driven some revelation in Wiseman, ironically matching the religious epiphanies sought by his subjects. While the film remains formally rigorous, compared to the absolute steadfastness of other Wiseman films it’s all but freewheeling. Scenes are driven, typically, by close-up shots of subjects’ faces, capturing their emotional fluctuations and personal quirks. Homing in on individuals is in itself a departure for Wiseman, who up until this point had shown little interest in characterising the denizens of the hospitals and dead-end towns he shot.2 Rather than ciphers for social archetypes, then, it’s individuality itself which the monks characterise. So many of their discussions and sermons emphasise the sanctity of selfless communal living; Wiseman captures many of the men’s moments of weakness, too, as they visibly grapple with the desire for individual personhood. While Wiseman subjects are ordinarily given space and camera time to speak, unadorned and at length, Essene’s monks are often off-screen while talking, the lens instead lingering on a non-speaker whose facial tics and momentary attention lapses speak volumes of the struggle between ascetic faithfulness and the foibles of human weakness. Moments taking place outdoors are also treated differently than the near-ritualism one would expect. A long scene late in the film explores another monk wandering the monastery gardens with a nun from a neighbouring convent,3 laying bare his regrets, challenges, and in the end his perennial optimism. A long, ragged one-take composition and the hefty philosophical ideas being discussed, combined with the man’s hippie-burnout appearance, make the sequence feel more like a scene from Out 1 than from the maker of the unerringly dense At Berkeley.

A final nod to the self-reflection contained at the core of the film’s themes can be found in some startling scene transitions. Not used frequently (and probably stronger for it), Wiseman utilises brief sets of static scenery shots to bookend scenes at a few points in Essene. We see the bleached wall of a monastery outhouse, nondescript parts of the gardens, and a cross mounted somewhere, all framed meticulously, and timed evenly before transition into the next-human-occupied shot. Oddly enough, they most noticeably evoke Ozu’s notorious ‘pillow-shots’, the seemingly functionless interludes deployed by the Japanese master between his scenes. While Ozu’s films of the family were purposefully and universally stagey in direct contrast to Wiseman’s focus on immediacy, their tendency to place value on quietness, sobriety, and decency seems to fit the American filmmaker’s project with Essene. Giving the viewer these moments of peace – the interlude shots, the close-ups, the meandering yet engaging discussion – serves as a rejoinder to the invariably frantic pace of Wiseman’s other early films. It’s an ingenious method for granting respect to the documentary’s subjects, men themselves seeking real introspection and restfulness, and showcases the value of unearthing the formative works of great directors. Less established in the role of great American institutional diarist than he is now, Wiseman both wanted and needed to make films as subtly challenging as this one.