“Do no harm”, and “protect the vulnerable” are two rules often brought up in discussions around the ethics of documentary film-making. Nowhere should they be harder emphasised than with HBO, and more applicable than in their European wing’s production of Toto and His Sisters, Alexander Nanau’s intimate piece on a trio of orphaned Romanian siblings. Saying they live in a harmful environment is like asserting that the sun sets in the west, though even that would come as a huge relief to young Totonel, who must sleep under a harsh tungsten glow in a drug den night after night. He and his tattered family couldn’t get more vulnerable either, with one older sister trying desperately to stay on the straight and narrow while another slides into the same cycle of self-destruction that has imprisoned their mother. While Nanau respects the role they have in creating their own narrative and has a mindfulness for the systems that keep them downtrodden, he keeps us locked in a remove that, however accomplished, never completely erases those concerns.

The children are scraped on the gravel by a foster system that can only retro-fit an education onto one they already have. Formal and informal learnings blend as Nanau tracks them between different social worlds of Bucharest, either hitting the pavement of the estate they live in or being under the care of teachers and, eventually, orphanage managers. We tend to find an adult making impositions upon them, and sometimes this works out, especially for young Toto and older sister Andreea, who never leaves his side during dance lessons. Other times, it’s someone keeping them in the small, drug-littered hole they are crawling out of, such as the judge putting oldest sister Ana behind bars or the young men shooting up in their messy apartment. Nanau not only shoots all of this in remarkable proximity but also sits in on the parole hearings of their mother, who is not so savage as you might expect of someone who has left their children with a near-absent uncle, but also doesn’t seem so aware Toto and Andreea’s wants as much as her own. In those moments, the penal system that keeps her separated is backgrounded by the situation she is adding to, and there are moments when his integration in the family unit begs the nagging question of whether he is doing something to make things easier on them.

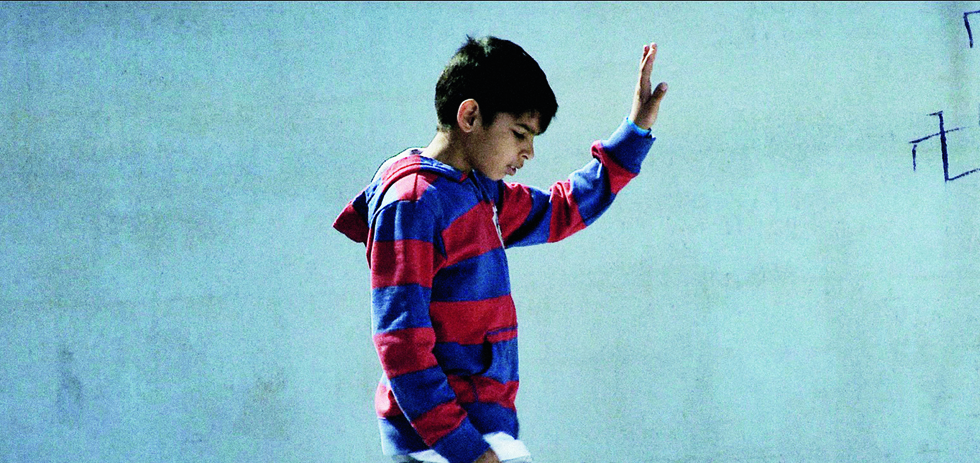

Answering that within the film, however, would break the smartly-judged absence of himself from the story. No-one ever makes reference to him, not even in the privacy of their home, and we are always drawn instead to the emotional meat of the story. This lies, fittingly, in Toto’s preserved innocence, and the simple determination by which he applies himself to a hip hop dance troupe. A poor urchin taking up body-popping reads like an American film plot of Sister Act-level appeasement, but it goes down well in this particular social climate because the well-to-do youths teaching the class create unwitting conceptual gaps between their world and the one waiting for Toto in the unit blocks. When the dance coach tells kids to depend on their teammates like their own parents, Nanau lets his obliviousness to Toto and co’s situation sit unchallenged, holding on Toto’s wandering gaze and finding Andreea in a tearful moment with a teacher later. This unobtrusive approach seems to be lessening the harm he might wreak on their lives just by being there for such vulnerable situations. Simultaneously, he and fellow editor George Gragg are unnervingly good at placing us in the right place at the right time, such as when Andreea declares out loud “oh bitter life, what have you done to me”, which may be an overdramatic translation but still smacks of a documentarian manufacturing an emotional beat. It’s a rare moment where his inherent imposition makes itself known, which is otherwise invisible enough for us to track the film’s real heroes and their dilemma.

The strongest antidote of all to those issues is the way in which the reins are occasionally turned over to Andreea herself. She uses a handycam to record memories and testimonials that become emotional highlights among the rest of Nanau’s material.1. A two-shot of herself and Toto looking at their recorded image, and the story they are authoring in real time, grants us greater access to their state of mind that their director, skilled though he is, can’t provide by himself. It’s also what saves an especially harrowing confrontation between Toto and Ana from being rankly voyeuristic, and that effect is present throughout the majority of Toto and His Sisters. He has given them many chances to find their own story and express their own troubles, free from the judgements of adults with ulterior motives, and that is a gesture of notable integrity.