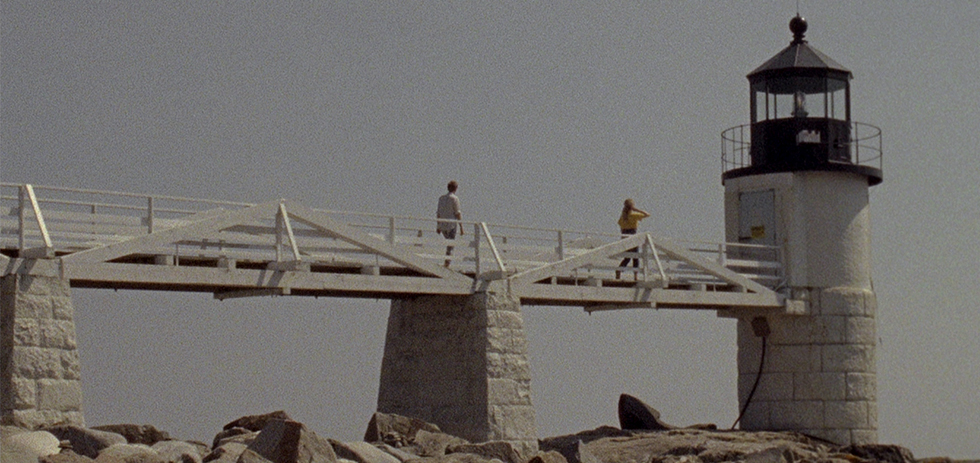

For the Plasma, the debut feature film from Brooklyn-based filmmakers Bingham Bryant and Kyle Molzan, is a strange and surreal look at the intersection of technology and nature, following two women in a remote cabin in Maine who monitor the surrounding forest and find a strange series of patterns. It had its Australian premiere this week at Grey Gardens Projects in Fitzroy and we were able to speak with writer and co-director Bingham Bryant ahead of the film’s second screening.

For the Plasma has screened in Berlin, in competition at the Belfort International Film Festival in France, in South Korea and now is having its Australian premiere at a new independent cinema in Melbourne. Why do you think your film has had this almost international appeal, at least in the world of film festivals?

Well, I think it’s a very American film, that’s very much tied to a particular landscape and to a particular history, which is that of this small town and nowhere else, but in terms of style, it’s working in territory that American films in recent years haven’t been comfortable with, even independent films. Very small films, like ours, and there are many good ones being made in America right now, but they tend to be naturalistic, and so we’re working in a mode that, I think, a lot of international film communities and festivals feel more comfort and familiarity with. But I also think there’s something about the film that people…either they love or hate it, but if they love it they feel like they almost adopt it in some way, it becomes this pet object of theirs, which is nice. I think it’s something akin to my own affection for the movie, which is something outside of me but that I have an irrational fondness for.

I think the film almost sets up this idea of each individual viewer becoming invested in it, specifically in the sequence where Helen is teaching Charlie how to read the trees and you just have this shot of the trees on a screen within the screen for something like a minute, minute and a half maybe, and you have Helen talking about looking for patterns in the lines. It’s this perverse sense of instruction but also lack of guidance, so the viewer is instructed to fill in their own blanks.

Yeah, absolutely. I’m very influenced by and interested in the nouveau roman, this movement in French literature that appeared in the late 1940s and 1950s, which were often dismissed as glorified choose your own adventure novels, so maybe this film is, to some people, a choose your own adventure film, but it does aspire to a similar sort of openness that those books did. Books by people like Nathalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet or Robert Pinget.

In that vein, it is something of a strangely literary film, though the only overt reference is to the Kōbō Abe novel (The Ark Sakura) it’s got this patience to it that doesn’t align itself to conventional structures, making it this oddly literary styling in what is clearly such a visually oriented film.

Abe is the most prominent literary presence in the film, or Abe’s books are, but there are a lot of quotations jotted in here and there, and they’re used almost as a textural element. Also some of Herbert’s dialogue, for example, is of a much more literary texture than the rest of the characters, and so it is one of many textural elements that are being pitted against each other, and seeing what sort of ideas and conflicts come out of that.

You studied literature at university, how did you make the leap into filmmaking?

Well, for me, literature and film and my interest in both have always run completely parallel; I’ve never been able to disentangle them from one another. I arbitrarily had chosen to study literature and pursue a career, probably, in publishing, because I sort of despaired at finding like-minded people or collaborators to work with [in film]. But then I moved to New York and met many wonderful people who ended up working on the film, it was actually Anabelle, the lead actress, and Kyle, my co-director, who brought me on board the film. After that had happened I had to face the facts and my repressed desire to make movies, and just stick with it.

So there was this sense of an almost collective of friends making this film? I know that the budget for For the Plasma was very small; you Kickstarted $12,000 for it?

Yeah, we did, and all of that [crowdfunding] was friends and family really. And the movie came out of this very particular little community. Back in 2012, when we shot the movie, it was very strong, but it’s almost dissolved now, as people have moved away from the city, as friendships have changed. At the time though, it was very strong, and this movie came out of that. There’s still, I think, a very good filmmaking community in New York, and there’s a lot of talent. I don’t think it’s being fully exploited at the moment, or fully put to use, but there’s an enormous amount of talent and an enormous number of people who do want to be involved in making films.

It does feel like For the Plasma would have come out of some kind of independent movement, considering when it was made and how it has been released through festivals. On that idea of there being this large amount of creative talent in New York, did you get a sense of the direction in which independent film in the city is moving when you were at BAM Fest?

Well, I think it’s a very interesting question. I think that there are definitely directions it’s moving in, some of which are worthwhile and interesting and some of which are not, but I find it hard to place this movie in the context of any particular tendency. I think there are some very good movies being made here but there is a lack of variety, and for me the real problem that this stems from is the lack of organisation here in the city. The independent film industry is not very organised, the resources are not very well-managed, and so you have films, mostly safe films, being made, or films being made just for the cheapest amount of money possible. Either way, I don’t think artists are really getting the freedom to move in more interesting directions.

I saw in a tweet from the For the Plasma account, I’m assuming it was you writing it, to an online troll arguing about piracy, but one of the interesting things you mentioned was the failure of production and distribution for young filmmakers. I guess through For the Plasma you were able to sidestep some of that and drum up, you know, ‘x’ amount of money, work with the right kind of people, and make a film that ends up on some pretty influential best of lists at the end of last year. You’ve almost rejected conventional systems in that sense.

Yeah, but the system that this film was made in is not one that – it was very, very difficult, not that it’s ever going to be easy, but it was extremely difficult and it took much, much longer than it should have, and we drew on resources which we’ll never be able to draw on again. The way that we made For the Plasma is a way that you can make a first film, but it’s definitely not a way you can make a second film. So what we have in place right now are structures where people can basically be over-reliant on their friends for everything from funds to labour, everybody worked on the movie for free, and that’s not an ideal situation, by any means. I think that the movie exists and I’m very thankful for that, but I feel plenty of guilt about how it was made, and in the future I would like to find ways that I feel are more ethical to make movies. It’s silly to talk about ethics when it’s such a tiny movie, but still I think there are ways to make films that treat the people that you work with, the people that you care about, better, and that are better for the films and the industry in the long run. Kickstarter, I think, is poisonous and I will never use it again. I don’t mind saying that now; I think that it’s really crippled the film industry. Any infrastructure that was in place before Kickstarter for small films has now disappeared or has been slowly weakened, and I think that it’s moved the industry in all sorts of bad directions.

It’s become almost a crutch for smaller filmmakers.

And it’s one that is suited increasingly towards, or works only for, more commercial projects.

I saw that Frederick Wiseman has just put his latest feature up on Kickstarter, he’s looking for post-production funds, which is insane.

Yeah, well everybody – people I really respect and love are doing it – [Abel] Ferrara just made a Kickstarter.

Wait, really? That’s insane. I’m gonna look this up now.

(Laughs) Yep. Abel Ferrara, the ultimate underdog, the ultimate bad boy, has got a Kickstarter. Because, if you walk into a production office now, you’re gonna have some numbskull producer tell you is “Ah, we’ve gotta get a Kickstarter program going” and I’m sure that happened to Abel too.

Ok, this Kickstarter page features a video of Wilem Dafoe reading the entire screenplay.

The entire screenplay? Now I kinda gotta watch that.

Ok, so it only made $18,000 of its $500,000 goal and the project is over. “Funding Unsuccessful” as of 20 or so days ago.

Well you’re probably aware of all of the mess that’s been going on with Orson Welles’ last film and how it’s probably one of the most important movies of the past 50 years, and it’s not gonna get the funding. It already didn’t get enough money, but then they restarted it with a lower goal and it probably still isn’t going to reach that. Meanwhile, you’ve got Spike Lee and people like him, who really should know better and can find funding through existing structures, older structures, using Kickstarter and undermining those older structures for the rest of us who would like to use them.

So you shot the film on 16mm and it looks absolutely gorgeous. The close-ups in particular reminded me of some of Sean Price Williams’ work on Listen Up Philip. I saw that he was originally attached to shoot your film on your Kickstarter announcement. What happened there?

Oh, well, Sean is one of our closest friends, we love him to death. But there was a scheduling confusion and so at the very last minute we found Chris Messina who, in addition to making the movie more beautiful than I could ever have hoped for, is also such a really angelic presence on set. So things turned out very well, and we still get to drink with Sean and hear all sorts of cranky stories from him every weekend.

Well I really like how the visuals for the film seem to move from being very loose and very free to being very static and locked on in the first ten minutes of the film. It helps foster this idea that much of the film isn’t able to be pinned down, it’s not ever really set in one style. Was that something you focused on when writing the script or something that developed on set?

Well, maybe this is giving the game away, not that it’s hidden; but when they’re in the house, Helen’s territory, the camera is locked down, and when they’re in the forest, it’s handheld, until the moments when the camera or technology reassert themselves and make their presence known in that context. So there is a little bit of a schema to it, but, yes, at the same time I wanted to have a style that would seem to have certain rules and then tease them and undermine them or even make fun of them. So sometimes the camera seems very stern and objective and rigid, and then it’ll do something quite silly. Little formal games like this were both important to the story and I think to our philosophy in general.

One of my favourite shots in the film is definitely one of the more silly ones, it’s a locked on shot when Charlie is sitting in the forest on her phone and then, at the end of that scene, the camera suddenly looks straight up. I wasn’t expecting that jump at all.

(Laughs) Yeah.

I have to ask, something that really does have a major impact on the creation of the film’s tone is its score, which was composed by Keichii Suzuki, who has gone from scoring Takeshi Kitano gangster films (the Outrage duo) to your Maine-set American indie. How did that happen?

Keiichi Suzuki has done some terrific score work, but we really brought him on board the project more because of the even more incredible work that he did in the 1970s and early 1980s. He was a very important figure in Japanese experimental music, in pop and electronic music, and the techno-pop genre that appeared in Japan in the early ’80s, influenced by but also parallel to what was going on in Germany and the UK. That music as a whole was amazingly coherent, amazingly rich in exploration of lots of ideas and concepts that were appealing to me, and that also started sneaking into the script: all of this stuff about technology and nature, about exoticism, about the relationship between the city and the country, things like that. And that was a huge influence on the ideas of the film. In the script there are many little references to this music. If you watch the trailer, which I know you have, it’s clear that some of the dialogue in that scene, the scene with the Japanese businessmen, is taken from a Naoto Takenaka song which was written and produced by Yukihiro Takahashi, who was one of Keiichi Suzuki’s major collaborators. So there’s a web of connections there. Suzuki was the head of one of the biggest bands of this era, so we reached out to him via email, not expecting that he would get back to us, but hoping against hope that he would. And he asked to see the film, which we sent to him with all of these apologies about what a tiny little movie it was, and he told us “no, it didn’t matter” to him, he was just interesting in being involved with projects that he found artistically stimulating (he’s a big cinephile as well), and he decided to come on board. I think that he would have already had his mark on the film whether or not he scored it, through the influence of his music in general, but, yes, he really completes it. I think it was the most natural fit imaginable, even if it is bizarre that this huge, huge star from Japan is scoring this tiny, tiny little movie shot in 16mm in Maine over a summer.

I think it fits wonderfully, every time the score comes in everything seems to come together. It seemed like your main focus in the film was in establishing tone, through the visuals and audio, moreso than focusing on the exposition. With that, though, I noticed that a lot of the dialogue in the film was dubbed over by the actors, it seemed fairly clear that was happening as well.

Yes, well, it was a mistake, it was a terrible blunder. We lost about 60% of the sound through sheer amateurism, and then we decided to dub it, and it was heartbreaking because, especially on such a small production, that’s such a huge amount of time and money that you don’t have spare to spend. But I think it does work with the atmosphere of the film. It adds an additional layer of contrast and tension between the various technologies at play. So, yeah, having this digitally recorded sound laid after the fact over this 16mm image, and having this very clear and crisp but also somewhat artificial sound…it somehow works. In a similar way I like how, even though we shot on 16mm and we’d love to see the movie projected on film some day, the fact that it’s only, in all likelihood, going to be shown on a DCP or a DVD or a Blu-Ray – that’s just an additional layer of tension between the digital image and the analog image.

I’d agree with that, I think it definitely creates this contrast and further distance in the relationship of the two women; as their friendship crumbles their dialogue feels more silted and less organic in delivery. It’s lucky you were exploring these kind of themes so it worked.

(Laughs) Yeah we got very very lucky, many times.

Why Maine?

Well —

Specifically, the Porter House – owned by a former astronaut, you explore space and satellite imagery near the end of the film – was that the reason you went to Maine or was it entirely a visual desire?

We’re New Yorkers, but the last thing we wanted to do was make another film set in our apartments. In general, I’m not really an apartment-minded person, and I wanted to make a film that was somehow about landscapes. The only way I could do that with such a small production was to write about a place that I already knew. So the town and the house became some of the fundamental materials of the script; every scene in the script was written for the locations that I already had in mind, that I already knew. It’s a very small fishing town in Maine that I spent a lot of time in as a child. So the entire movie is suggested in a strange way by these real locations. I think how it ended up was that, even though the film is very bizarre and unrealistic, there’s something concrete about it too, because it really is based on a real place, and it ends up being a dream, that I’ve had, but also that the place has had about itself. It’s not entirely my imagination: it’s something outside of my imagination’s imagination as well.

The film’s thematic concerns fit the landscape like a glove. There’s that wonderful shot of the physical wooden frames of vision hanging out in the forest, where the camera pans over to see around eight of them, which almost encapsulates this mesh of digital and real.

Thanks. Oh man, you didn’t ask the question I was sure you would ask!

Wait, what question?

About 4:3, the aspect ratio – it’s the name of your site, and the film was shot in it.

Oh yeah.

You’ve screwed up.

(Laughs) Yep. Actually – on the aspect ratio, your film and the film I watched right before it, Jenni Olson’s wonderful The Royal Road, have a strange amount in common. They’re both shot in 4:3, microbudget, abstract plots, shot on film and both make me feel like I immediately need to go out and watch a whole heap of films by very specific directors. For hers it was essay filmmakers and Chantal Akerman but for yours it’s like Rohmer and Rivette. It’s giving me the impetus to go out and see things I’ve been meaning to see.

(Laughs) I’m very glad to hear that.

That’s the highest compliment that I can give, your film makes me want to watch more film.

We avoided having cinephilic references, but when I watch it it feels very loving towards the medium. I’m not entirely sure where that’s coming from, but it’s there.

Thanks a lot for taking the time to talk with me.

Thanks a lot Conor.

For the Plasma screens again at Grey Gardens Projects on the 12th of July. Tickets can be purchased here.