Reflecting on the disastrous critical and commercial response to the release of his film Graffiti Bridge in November 1990, Prince predicted, “maybe it will take people 30 years to get it”.1 It seems unlikely that this anticipated renaissance will occur on a mass scale anytime in the next five years, yet its 25th anniversary offers a chance to reconsider Prince’s third directorial feature anew. A sequel of sorts to Purple Rain, Graffiti Bridge once again pitted the pompous, retro absurdity of Morris Day against the struggling, ennui-driven genius of Prince’s character, The Kid. Most concretely, Graffiti Bridge explicitly references the plight of Kid’s parents from the earlier film, as we discover that his mother is institutionalised in what Morris describes as a “nuthouse”, presumably as a result of his abusive father’s suicide that understandably still haunts Kid.

Grossing well over $150 million worldwide, Purple Rain was a pop cultural phenomenon, even knocking Ghostbusters from its dominant US box office position in its first week of release in July 1984. It was the feature debut for director Albert Magnoli, who’d garnered a strong industry reputation on the back of his celebrated student film Jazz in 1979. Purple Rain combined Magnoli’s passion for and knowledge of music with the experience of co-writer William Blinn, who was responsible in large part for the success of the television series Fame.2 Magnoli certainly knew who Prince was, with 1999 being Prince’s first Top Ten billboard album and was the fifth highest selling album of 1983. But it was Purple Rain that launched him into superstardom and made him an icon. A meeting between Magnoli and Prince to discuss the film project over spaghetti and orange juice at a diner was all it took to consolidate their professional relationship, one that would culminate with Magnoli briefly becoming Prince’s manager during the production phase of Graffiti Bridge.

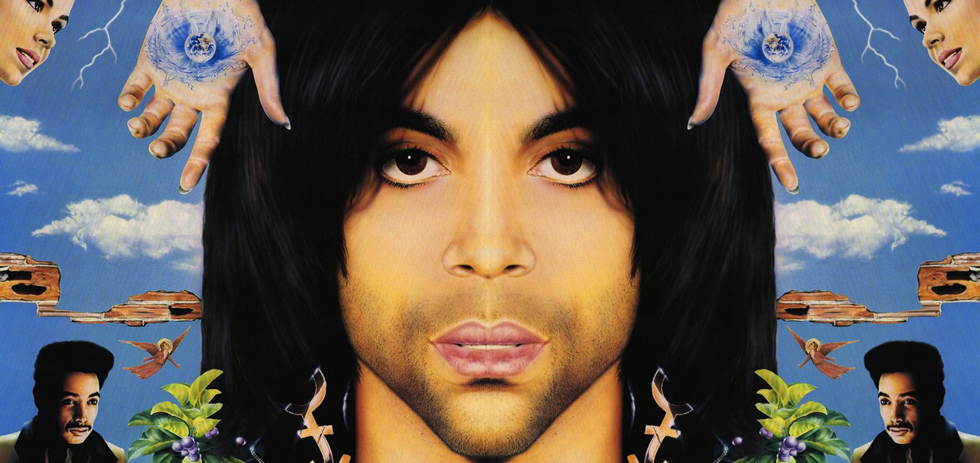

Although promoted as a loose sequel to the 1984 film, the aesthetic drive and thematic focus of Graffiti Bridge deviated from Purple Rain in fundamental ways. The semi-autobiographical Purple Rain tells of a rock star man-child in a state of romantic, artistic and familial crisis. Rendered visible in the film’s iconic costume design and Prince’s own twist on ’80s gender-bending, the Kid oscillates between feminine and masculine: on one hand, he contends with the reality that his mother is the victim of domestic violence at his father’s hands, while at the same time resisting the collaborative impulse of band mates Lisa and Wendy.3 Aside from its epoch-defining soundtrack, Purple Rain was a euphoric addition to the contemporary backstage screen musical. Beyond raunchy gags about the correct geographic location of Lake Minnetonka and lewd songs about hotel lobbies, it was Prince’s irrepressible star persona that made Purple Rain one of the most beloved and enduring musicals of the 1980s.

Prince embarked on two other film projects between Purple Rain and Graffiti Bridge. The first of these was 1985’s Under the Cherry Moon, initially intended for director Mary Lambert. Known primarily for her cult horror film adaptation of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary in 1989, at this stage Lambert’s reputation was linked to her work as a music video director.4 Pre-production hiccups led to Prince making his directorial debut with Under the Cherry Moon, ensuring – from his perspective, at least – that his vision of the film would come to fruition. As became clear upon the film’s release in mid-1986, however, that vision was not one that appealed to audiences or critics.

Set in a vague, anachronistic past and shot in black and white, Prince audaciously chose against merely repeating the successful Purple Rain formula, and also refused to adhere to a traditional screen musical format. Aside from the dazzling “Girls & Boys” performance sequence and the use of the hugely successful Parade album as its soundtrack, Under the Cherry Moon opted instead for a comparatively music-free method of telling the tale of Prince’s lounge lizard Christopher Tracey as he parades across Europe, inadvertently falling in love with his trust funded prey, Mary Sharon (Kristin Scott Thomas).

Under the Cherry Moon is at times goofy, even clumsy, but it refreshingly replaces the earnestness of The Kid with Christopher’s wicked sense of humour, flirtatiousness and cheekiness. These are precious aspects of Prince’s star persona, and while we see flashes of it in Purple Rain, here it is fleshed out to form the basis of an entire character. But aside from grossly underestimating how negatively critics and audiences would respond to a Prince film almost completely bereft of musical performances, Under the Cherry Moon suffers most significantly from an absence of electricity between its romantic leads. Christopher and Mary certainly look like they’re having fun, but as far as on-screen sparks go the real energy is between Prince and his ‘business partner’, played by Jerome Benton.

While condemned to the critical dustbin as cinematic Europudding, there is a lot to love about Under the Cherry Moon. For starters, as the debut feature for Kristin Scott Thomas, it warrants far more recognition as the launchpad for this enigmatic, important actor. And even at its silliest, Under the Cherry Moon looks exquisite: production designer Richard Sylbert had worked the previous year on Coppola’s jazz era extravaganza The Cotton Club, and the director of photography was another Coppola collaborator-to-be, Michael Ballhaus. But Ballhaus’s importance to Under the Cherry Moon lies as much in his association with celebrated German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder, with whom he worked on sixteen films including The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (1972), World on a Wire (1973), and Chinese Roulette (1976). Under the Cherry Moon wears its wannabe European-ness proudly on its sequinned sleeve, and the project was conceived as much a homage to Federico Fellini’s 8½ as it was Abbott and Costello.

Fellini may be an overly generous point of comparison for a film that ultimately boils down to a gender-reversal of pre-code subgenres like the screwball comedy and the gold digger film. Yet this alone is worth further consideration: Under the Cherry Moon has an essentially queer aspect to it, if only because Prince is shot like a woman in Classical Hollywood cinema in virtually every scene. This perhaps has less to do with conscious ideology than Prince’s trademark ego, manifesting via the obsession Prince-as-director clearly has with the image of Prince-as-actor. Under the Cherry Moon champions the pop star’s unwavering fascination with what in Mulveyian terms is his own “to-be-looked-at-ness”. At the very least, Under the Cherry Moon is a refreshing viewing experience simply because it is a pop cultural artefact that euphorically embraces a blurring of masculine and feminine, an act that marks Prince’s broader star persona more generally.

Under the Cherry Moon’s soundtrack, Parade, is at the centre of what is undoubtedly Prince’s strongest musical period, bookended by Purple Rain (1984), Around the World in a Day (1985), Sign o’ the Times (1987) and Lovesexy (1988). Sign o’ the Times would provide Prince with his second feature-length directorial project, a vibrant concert film strung together by brief narrative vignettes. In more ways than one, it is a stepping-stone between Under the Cherry Moon and Graffiti Bridge: with its saturated colours and penchant for poetry, like the latter it too was shot predominantly in a studio.5 At the same time, the “U Got the Look” sequence in Sign o’ the Times with Sheena Easton alone allows connections to be made back to Under the Cherry Moon, both stylistically and narratively.

In her essay “’Joy in Repetition’?: Prince’s Graffiti Bridge and Sign o’ the Times as Sequels to Purple Rain”, Marie A. Plasse shrewdly seeks deeper readings of Graffiti Bridge than merely a “failed sequel”, and argues that if Graffiti Bridge is the “cinematic alter ego” of Sign o’ the Times, then it is also the “alter-sequel” to Purple Rain. Ego may again be a key word in the Graffiti Bridge story, with a solo Prince taking on directing, starring and writing duties. By some accounts, so wobbly were his skills in the latter that he fired his long-term management team Cavallo, Ruffalo and Fargnoli when they warned him how dreadful the script was. But with the combined promise of a Purple Rain sequel and Prince’s lucrative involvement with Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman – where he met Kim Basinger, the two embarking upon a highly publicised romantic relationship – Warner Bros. forgave Prince all past filmmaking sins, and invested in Graffiti Bridge.

Both Basinger and Madonna were approached to play the female lead Aura, Basinger having also collaborated with Prince on an earlier draft of the film. Madonna rejected the role outright, yet his work on arguably her finest album, Like a Prayer (1989) – he played the guitar uncredited on “Keep It Together”, “Act of Contrition” and the title track, and sang with Madonna on the duet “Love Song” – stands as testament to the successful collaboration of two of the most important figures of late 20th century pop music. Come 1990, changes to the Graffiti Bridge project came thick and fast: Prince separated with Basinger in January, and began filming a month later. The bulk of the primary photography was completed within a month and a half.

Third choice for the role of Aura behind Basinger and Madonna was Ingrid Chavez. Legend holds that Prince and Chavez met while on ecstasy in 1987, and she instantly became his informal ‘spiritual advisor’. Under her influence, rumour also suggests that he delayed the release of the Sign o’ the Times follow-up The Black Album until 1994, instead releasing the tonally opposite, heavily spiritual Lovesexy album instead. Chavez is credited on the liner notes of Lovesexy as “the spirit child”, and is broadly considered a strong influence on that album in particular. As a poet and musician in her own right, Prince and Chavez began work on her solo album in 1987 (although it was not released until after Graffiti Bridge in 1991). While the album May 19, 1992 was not a thundering commercial success, tracks like the slick single “Elephant Box” encapsulate her breathy, spoken word style. In a biography of Chavez’s one-time husband David Sylvian, Martin Power describes Chavez’s sound as a hybrid of Eartha Kitt and Tori Amos, but it can arguably be demonstrated more immediately through her input as co-writer (with Lenny Kravitz) on Madonna’s 1990 hit “Justify My Love”.

Chavez’s floaty, ethereal presence – symbolised in Graffiti Bridge by the obvious visual motif of a white feather – is a cornerstone of the film. For better or for worse, Prince could not have made Graffiti Bridge the way he did if he wasn’t in love with Ingrid Chavez to some degree. Of all Prince’s leading ladies, while certainly not the strongest actor, Chavez is the one with the most electric connection to Prince on screen. An angelic tomboy, in Graffiti Bridge she is a ’90s pop cultural Orlando. Appearing as much through disembodied voice-overs as a barefoot vision in a floral frock at the film’s eponymous bridge, that Chavez’s aura exists on a different plane to the more down-to-earth gangster plot of the film was a conceptual rupture both conscious and thematically profound, but it was also fundamentally detrimental to the film’s commercial and critical success. Unlike Purple Rain, here the Kid needs more than what was on offer by the sex-shooting, 19-year-old Apollonia.

It would be pointless to argue that Graffiti Bridge isn’t all over the shop from the very outset: colliding flashbacks randomly intersect with confusing, multi-stranded narratives before the credits even end, and the first coherent sequence is the less-than-memorable image of table full of gangsters earnestly eating hot chillies straight from a jar. Yet the film’s energy explodes with a live performance of the infectious single “New Power Generation” as snogging couples and seemingly possessed dancers lose their collective shit, a clever mirroring of the opening “Let’s Go Crazy” sequence in Purple Rain. In the space between the two films, Kid has evolved from performer to club owner. Yet old tensions with Morris (again played by Morris Day) have only escalated as the latter seeks full ownership of Kid’s club, Glam Slam.

Heavily recalling the aesthetics of the Sign o’ the Times concert film, Graffiti Bridge’s deliberately synthetic-looking studio locations are captivating in their knowing acknowledgement of cinematic artifice. On this front alone, it is a universe away from the comparative quasi-realism of Purple Rain. Only at times are there flashes of the ‘real’ world – shot on location – in Graffiti Bridge, establishing a knowing, diegetic distinction between ‘here’ and ‘there’, and mirroring the film’s most important spatial binary: that between the earthly and the divine.

It is precisely this unresolved (and arguably unresolvable) tension between the ethereal concerns embodied by Aura and the more earthly demands of property ownership that lost audiences. The film is at times openly ambivalent about the latter, privileging Chavez’s poetry as it floats over the surface of the film. Graffiti Bridge is heavy with voiceovers; it is a world where internal thoughts mean much more than mere actions. Graffiti Bridge may have bombed, but it was ironically successful in bringing to life that which Prince had always been wanting to say through both filmmaking and his music: the path into our souls, minds and hearts is essentially somatic, and music and sex are the keys. He so much as says this in the lyrics of “New Power Generation”, singing “making love and music’s the only things worth fighting for”.

Given these concerns, the musical is a perfect vehicle for what Prince wanted to do with film. Lessons were learned from the commercial and critical failure of Under the Cherry Moon, and Graffiti Bridge is heavily structured by music performances. While Purple Rain was undeniably conscious of the heritage of the screen musical, its ancestors could most generously be pegged as grittier ’70s musicals like New York, New York. Graffiti Bridge, however, is more a mash-up of Xanadu (with its focus on divine, angelic feminine intervention to help out a lost earth bound artist), and – in regards to its final scene in particular – the overt god-bothering of Godspell.

Of the four feature films Prince was involved in during this period, Graffiti Bridge is the one least interested in realism or narrative logic, precisely because it is a film concerned with the spiritual plane. Tragedy is inevitable, but foreshadowed so strongly that it feels the narrative is almost indifferent to it, particularly in the consciously stagey world the film has fought so hard to articulate as a construction. Aura never belonged ‘here’, because ‘here’ – with its real estate dramas and material concerns – is not real. Lying in bed together, Kid writes “mine” on a heart shaped notepad (during a strangely inappropriate game of snuggle-time hangman). Aura replies, “no baby, his” as she points to the heavens. The Kid realises he has a romantic competitor he cannot compete with, and is humbled by it. It would be another eleven years before Prince would become a Jehovah’s Witness, but if the groundwork wasn’t visible for this conversion earlier, in Graffiti Bridge it becomes inescapable. At this stage, however, the overt sexuality of songs like “Scarlet Pussy” was only two years earlier, and upcoming singles like “Gett Off” and “Sexy Motherfucker” still demonstrated that there was yet some way to go before fully transcending the sins of the flesh.

Graffiti Bridge may be far from perfect, but it is also a fascinating film in a number of ways, due as much to its strengths as its weaknesses. In one sense, as Matthew Carcieri, author of Prince: A Life in Music (2004), pointed out, it may have simply because the message it sought to impart was so out of sync with what was popular in the mainstream at the time:

Like its forefather Purple Rain, the Graffiti Bridge drama turned on a conflict that was semi-autobiographical. The Time performed ‘black’ rap tunes, like “Release It” and “Love Machine”, that the movie depicted as demonically sexist and spiritually bankrupt. Prince, on the other hand, was a misunderstood genius who found vindication in the affirmation of a higher power.

Morris and his real estate tycoon plotline is connected to the earthly, and by diegetically dismissing these concerns in favour of its more spiritual aspects (personified by Aura and Kid’s relationship), Graffiti Bridge inadvertently dismisses the more traditional aspects of its own plot. We see here a resolution to the crisis that the Kid struggled with in Purple Rain, as he finally transcends trauma and discovers a more spiritual means of fulfilment. But in 1990, the year’s most successful films included Home Alone, Pretty Woman and Kindergarten Cop – the earthly still had sway. At the same time, Graffiti Bridge was released on the same day in the United States as the much darker and more serious Jacob’s Ladder, rendering Prince’s film by comparison as little more than trivial pop confectionary. And of course, the biggest grossing film that year worldwide was Ghost, evidence that while the mainstream were open to a bit of romantic pop-mysticism, it worked best if framed through the old timey (and emphatically white) nostalgia of The Righteous Brothers. Maybe Prince was right – it might still take another five years for Graffiti Bridge to be fully appreciated. “It was one of the purest, most spiritual, uplifting things I’ve ever done,” he said, “they trashed The Wizard of Oz at first, too.”