The strange and often unwelcome cottage industry of English-language European-made historical fiction productions continues with Philipp Stölzl’s The Physician, an entertaining enough adaptation of Noah Gordon’s novel hampered by humdrum plotting and a ludicrous failure to cleave to any semblance of real cultural history. Set in the 11th century and revolving around a young Englishman who, enthralled by the potential of the then-radical medicine practiced in the Middle East, sets out on a vast pilgrimage to meet and study with the renowned Ibn Sina – the real figure of Avicenna – the film’s beginnings frame it as a worthy attempt to channel Kingdom of Heaven and the thousand other sword-and-sand quasi-historical works of the last decade, but to refrain from their often orgiastic body counts in favour of an exploration of the history of ideas. It soon becomes clear, though, that The Physician lacks the commitment to going against the cinematic grain required to abandon its basic Orientalism, or to possess any real interest in the Jewish identity around which its plot revolves.

This flirtation with Judaism comes about when the protagonist Rob Cole (Tom Payne), an orphan travelling England with Stellan Skarsgard’s bloodletting barber-doctor, is introduced to a travelling Jewish physician who heals the barber’s cataracts. Deciding to travel to Isfahan in modern-day Iran, he discovers that he will be forced to pose as a Jew there, as Christianity is proscribed on pain of death. Rather than explore Cole’s assimilation into a medieval Hebrew identity, though, the film goes for the lurid and superficial right off the bat – before even leaving for the East,1 Cole performs a circumcision on himself, in a scene rendered ineffective by its lack of emotional context and bizarre underacting. Without a well-established personality other than that of the boilerplate scallywag fantasy hero, what should be a morbid ritual signifying Cole’s adoption of an alien identity is reduced to a plot device allowing for the inevitable later big reveal. It’s telling, too, that the film doesn’t seem to think that Cole’s lack of ability to speak Hebrew or Arabic will hinder him in Persia, but that an intact foreskin will, nefarious Muslims apparently being extremely concerned about everybody’s penis.

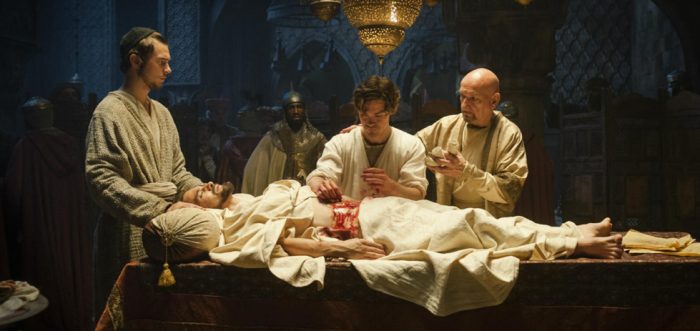

While the film’s parade of vague historical caricatures doesn’t cease once Cole arrives in Isfahan, it does at least broaden its scope to take in some genuinely interesting places and practices, all of which are designed and shot with flair by DP Hagen Bogdanski, whose previous work on the sublime The Lives of Others relied on the same kind of use of cloistered, compartmentalised space as The Physician’s evocative Persian arches, gates, and alleys. Once Ibn Sina (Ben Kingsley) is introduced, Cole’s increasing involvement in his medical and philosophical lessons intertwine nicely with rising political instability, and the threat of war with hardline Seljuks unimpressed by Ibn Sina’s relative secularity. On the other hand, while Kingsley’s performance is as measured and patrician as the role demands, it’s stilling galling to see him here at all: as a Brit of Indian descent, Kingsley’s most famous role as Mohandas Gandhi was rightly praised as a watershed in representing people of colour in Hollywood, whereas he has no Central Asian ancestry that I know of. These kinds of casting practices are obviously universal, but unusually irritating in a film which professes to explore the power of education and innovation to break down cultural barriers.

Towards its climax, The Physician’s crass revisionism and representational rashness show few signs of abating, and the tacked-on romance plot between Cole and Rebecca (Emma Rigby) is less than interesting in the face of the power struggle and plague revelations at the heart of the plot. More ridiculous still is the semi-supernatural ability to predict another’s death granted to Cole, which feels as though it was mentioned only so it could apply to his master in a climactic scene which is also totally ahistorical, Avicenna in truth not passing away until several decades later, of natural causes. While historical accuracy isn’t a requirement of every film set in the past, there is an uncomfortable implication in his on-screen death which expresses the core issue with films like The Physician: in order for films set in cultures of Otherness to ‘work’ as products in the West, their every aspect must be exoticised by a noble suicide, a seven-veil striptease, barbarians at the gates, or the like. For all its engrossing storyline and evident style, The Physician is doubly guilty in not only sticking to this Orientalism, but doing it in a work ostensibly committed to cultural history.